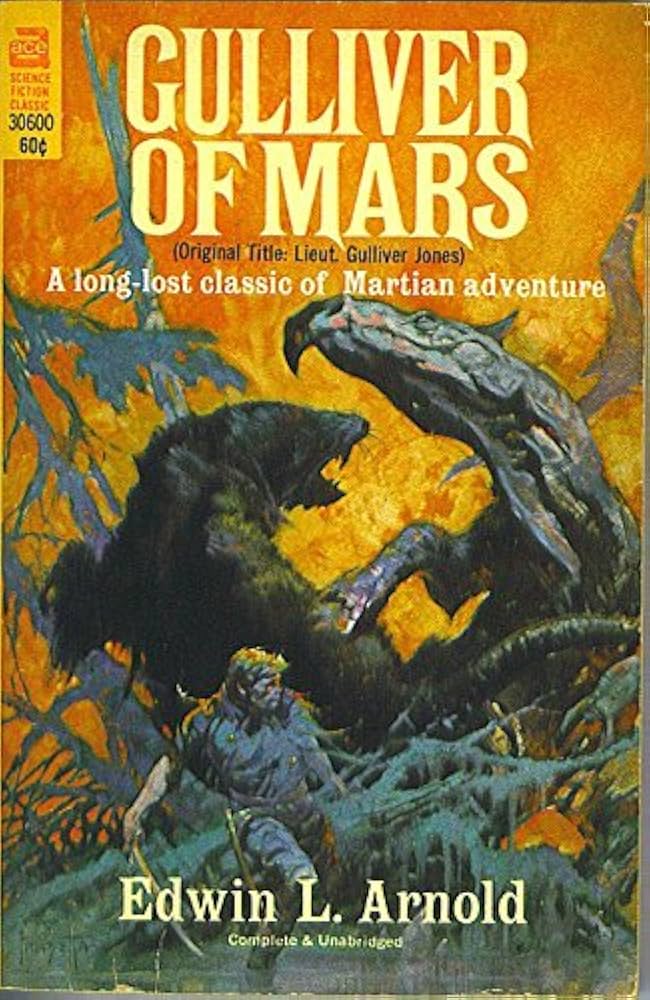

Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation by Edwin Lester Arnold

Thursday , 1, May 2025 Fiction Leave a commentThis is a guest post from Richard:

“In short, I am an ignoramus, but pretty well for a yeoman.”

This testament of John Ridd, delivered at the outset of R D Blackmore’s LORNA DOONE, could be accorded to Gullivar Jones. The eponymous hero of Edwin Lester Arnold’s planetary adventure of 1905. And with equal justification.

A bluff oafish naval lieutenant, Jones is neither particularly bright nor overly perceptive. His outlook on life is distinctly short-term. And while he is brave enough, his courage is of the dogged rather than dashing variety. All told, an unprepossessing sort of hero when reduced to brass tacks.

That being said; for anyone with an appetite for the “simple tale told simply” a more affable, engaging, convivial and amusing narrator one would be hard pressed to find. And this remains the book’s saving grace. Because the story which Jones is obligated to tell is an absurd concoction of contrivances, conveniences, and coincidences. One which ultimately collapses into full blown melodrama.

Traipsing the streets of New York one night, a disgruntled Gully Jones witnesses the crashing to earth of a flying carpet. From this is disgorged a swiftly expiring occupant. Who he is, and from whence he comes we never learn [one of several narrative cul-de-sacs]. Because shortly afterward an ill-considered wish, expressed whilst stood upon the carpet, results in Jones being transported to Mars.

There he is befriended by the Hither folk. These are the frivolous moribund dregs of a once mighty race. There too he is quickly smitten by Princess Heru, that “sodden little morsel of feminine loveliness.” When she is subsequently abducted by emissaries of the more vigorous Thither people from across the sea, Jones sets out to rescue her.

And that constitutes the entirety of the plot. The interval between initial resolve and retrieval being occupied by a succession of self-contained episodes and unbelievably fortuitous encounters. None of which are uninteresting by any means, but which only rarely summit any notable creative heights.

The book’s standout sequence occurs when Jones journeys up the River of the Dead, and finds himself marooned in a vast icy basin occupied by a multitude of frozen corpses.

The Mars that Jones sets out to explore is not conspicuously alien in composition. Its flora and fauna are of recognisable types, and only really differentiated from terrestrial varieties by virtue of size or colour. Also, there are no discrepancies in atmospheric pressure, gravity or solar radiation noted by which to invest Jones with superhuman powers. He remains throughout the same mortal there that he was on Earth.

As the scholar and critic Roger Lancelyn Green observed, Arnold does not appear to have been particularly interested in Mars. His depiction of the planet makes no concession even to the limited knowledge of it available to him. He doesn’t even take the trouble to draw attention to the two moons in the sky. An undeniable corroboration of where he was which might have forestalled Jones’s initial tiresome show of effected disbelief. The planet simply serves the purpose of being a convenient Never-Never Land to suit Arnold’s polemical ends.

And those ends are most apparent in the distinctions he draws between the dissolute Hither folk, who idle away their lives in endless recreation, and varying states of inebriation. And the brutish but energetic Thither people.

Presumably, Arnold’s intention was to alert his Edwardian readers to the perils of complacency post entente cordiale, in the face of waxing German militarism. For speculative fiction of the imperial period is replete with such dire warnings, and awash with savages serving as surrogates for the ‘beastly Hun.’

If so, then the objective is undermined both by his own absence of fervour, and the lack of conviction about either of the contrasted cultures. While it is possible to argue that the wooden stockaded capital of the Thither people does succeed in providing an adequate facsimile of barbarism, there is nothing remotely credible about the listless indolence and chronic inertia under which Hither society functions.

All activity in Seth, the Hither city, rests upon the obliging servitude of a caste of yellow robed androgynous slaves. Their service is explained as being a matter of convention rather than coercion.

Arnold had lived and worked in India for several years. And it is possible that he was drawing upon the social divisions he had observed there in formulating this conceit. However, to credit this book with ethnological concerns and commentary would be to elevate it far beyond its limits.

Incongruously, Jones offers no opinion of his own on the institution of slavery. Which for a northern republican of the period rings false. Conversely, he occupies two entire pages interrogating the slave An on the ambiguity of its gender. An on the nose rhetorical excursion that would doubtless earn Arnold a visit from the identity Gestapo if written today.

Just as the Hither society lacks credence, so Jones similarly fails to convince as an American seaman. Although his speech is sprinkled with nautical idioms, he expresses them in the manner of a London costermonger. It must be supposed that Arnold felt the need of a foreign perspective to provide safe distance between himself and his disputations.

Yet although his nationality may be only a convenience, his infectious, self-effacing and buoyant personality make Jones unfailingly good company. And his wry ruminations exhibit Arnold’s cordial prose style to its best advantage. Which is not beyond venturing into instances of authorial self-censure.

Such as when Jones opines:

“That is the worst of some orators…they never know when they have said enough.”

Arnold was often guilty of excessive proselytising in his work, and there is an engaging ruefulness at play when Jones terminates a discourse by “sinking [his] fists deep in his [opponent’s] throttle.”

LT GULLIVAR JONES: HIS VACATION is commonly described as a pioneering scientific romance. Yet as its hero’s name attests, it is more properly a satire in the Swiftian mode. Garnished with elements drawn both from Homer and H G Wells. And it remains equally true to say that it is a book now never discussed in any capacity than its connection, or otherwise, to A PRINCESS OF MARS. This would not be half as irksome if the reverse also held true. Yet it does not.

Arnold’s book has none of the verve or intensity of Burroughs. Its flights of imagination pale into insignificance by comparison. And anyone coming to it fresh from Barsoom and expecting similar fare is likely to be surprised and disappointed. And frankly bemused by its abundance of dancing.

Appealing fellow though he is, Gullivar Jones is no irrepressible superman. He considers abandoning his pursuit of the abducted Heru on several occasions. Contemplates suicide once. And while perfectly capable of knocking the odd antagonist head over heels, does not heap steaming corpses around himself with a dripping blade. In short, he is no John Carter. And the vapid and vacuous Princess Heru is no incomparable Dejah Thoris.

Had either author elected to set their stories anywhere else but Mars, the comparisons would not be so natural to draw. By doing so, Burroughs attracted unnecessary attention to his creative filching.

Vastly different in many ways the books may be. Yet sufficiently similar in others, that only a wise monkey could conclude that the one might be produced so few years after the other in total ignorance of its existence.

To label Burroughs a creative pirate might be putting it too strong. Although it is worth making the point that Kipling considered him the “genius of the genii” insofar as Mowgli copiers went. What Conan Doyle made of Caspak, the LOST WORLD of the Antarctic, is unrecorded.

Perhaps it might be more appropriate to limit the censure to a negligence in crediting his influences. A currently fashionable bibliophilic crusade.

Such heinous shortcomings not being the preserve only of the socially deplorable, after all.

Please give us your valuable comment