Months after a Lupin doppelganger is sentenced to death and hanged, Lupin III returns to the limelight, stealing a number of legendary artifacts tied to longevity on the request of Fujiko. Meanwhile, her mysterious benefactor tries to woo Fujiko, promising immortality to his personal Helen of Troy. But when Lupin double-crosses Fujiko to learn the identity of her benefactor, he finds himself in the middle of web of deceit drawing in a reclusive billionaire, clones of history’s greatest men, and the might of the United States’ military, all around one name: Mamo.

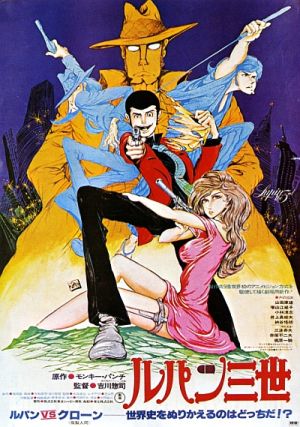

Originally titled “Lupin vs. the Clones,” 1978’s The Mystery of Mamo is the first Lupin III movie. Hampered by the restrictions of network censors, the Lupin franchise sought to use the creative freedom of the silver screen to create a faithful adaptation of Monkey Punch’s manga in tone, humor, and artistic style. While future animators would draw inspiration from The Mystery of Mamo, as 2001’s James Bond meets the X-men action caper Read or Die would retread its plot, it would be overshadowed by 1979’s The Castle of Cagliostro.

What a difference a year makes.

To be fair, not many anime films fair well when directly compared to a Miyazaki film. Taken on its own merits, The Mystery of Mamo is a delightful heist film that takes a deliberate turn to the strange and the science fantastical at the half way point. The cloning madness is out of place, even in the occasional science fiction adventures that every adventure hero inevitability gets involved with. Instead, the cloning and spaceships would be more at home among the Hermeticists, Nymphs, and Chimerae of John Wright’s Count to the Eschaton sequence. But when the chases and thievery keep to the terrestrial settings of Egypt, Paris, and Columbia, the film is at its best. Even when a giant semi resembling Optimus Prime’s steroid-using brother is trying to crush Lupin’s car under its wheels. However, since Castle of Cagliostro created the new formula for the series, The Mystery of Mamo instead represents the last hurrah of the Monkey Punch way.

To be fair, not many anime films fair well when directly compared to a Miyazaki film. Taken on its own merits, The Mystery of Mamo is a delightful heist film that takes a deliberate turn to the strange and the science fantastical at the half way point. The cloning madness is out of place, even in the occasional science fiction adventures that every adventure hero inevitability gets involved with. Instead, the cloning and spaceships would be more at home among the Hermeticists, Nymphs, and Chimerae of John Wright’s Count to the Eschaton sequence. But when the chases and thievery keep to the terrestrial settings of Egypt, Paris, and Columbia, the film is at its best. Even when a giant semi resembling Optimus Prime’s steroid-using brother is trying to crush Lupin’s car under its wheels. However, since Castle of Cagliostro created the new formula for the series, The Mystery of Mamo instead represents the last hurrah of the Monkey Punch way.

The Monkey Punch influence is, by design, all over The Mystery of Mamo. Zenigata’s crossed-eyes add a mania to his obsession in catching Lupin. Lupin’s heists and escapes are planned instead of improvised, making use of liberal traps and explosives. Lupin’s gleeful delight in the misfortune of others is always close by. The master thief has eyes only for Fujiko, and their seductions are more intimate and physical than the fencing with words that typifies their later relationship. Sex is an occasion for humor, and bad people take their pleasure in another’s pain. Life is cheap, whether for goons or innocents, and collateral deaths are the norm, not the rarity. Mamo’s goons light up a Parisian cafe just to try to kill Lupin and Jigen. Goemon’s honor can and does put him at odds with Lupin’s selfishness, to the point where he leaves the gang for a time.

And in a year’s time, all this will be gone from the franchise.

I have made much about Miyazaki’s additions to the Lupin franchise and how they defined nearly 40 years of following works. By adding a heroic goal to Lupin’s normally selfish ones, he transformed a sociopath into a franchise hero. In the process, the master thief’s penchants for cruelty, seduction, and murder were tamed. At the same time, Miyazaki removed another necessary element that set the Lupin style, one that is most apparent with Fujiko Mine.

Fujiko Mine has long posed a puzzle to Lupin screenwriters. Her design and portrayal have varied wildly in the fifty year history of the franchise. At one extreme, she has been a glamorous socialite, an evil Emma Peel, quick to seduce and be seduced. At the Miyazaki extreme, she’s a sexless mercenary. About the only consistencies in her design are her catsuit, her motorcycle, and her impressive silhouette. As a character, she’s come a long way from her origins–as a double entendre name for a parade of 60s centerfold socialites. With each new adventure, Lupin’s growing conquests would share the name of “Little Mountains.” The demands of the manga production schedule quickly pared the running gag into the cat burglar we know her as today, although she kept her worldly glamour and courtesan ways. But the censors were not comfortable with the mores of a 1960s sex kitten, and neither was Miyazaki. When he introduced Clarisse, he not only stripped Fujiko’s sensuality from her, he stripped the glamour from the franchise. Since Castle of Cagliostro, the love interests in Lupin films have been younger, more innocent, and just plain cute.

To better illustrate the difference, let’s look at a chart from a Virginia Postrel article on the difference between cute and glamour:

Fujiko embodies the ageless, mysterious, sophisticated, exotic desire and sex appeal associated with glamour. Her poses are drawn to entice longing in Lupin and the audience. Clarisse, Murasaki, and Rebecca instead are child-like, innocent, vulnerable, endearing girls with big eyes. Even tough girl Oleander has more in common with the vulnerability of the cute than Fujiko’s worldly glamour. This shift changes the relationships Lupin has, as in the manga, where glamour reigns, he wants–and gets—sex. But the cuteness brigade brings out the big brother and the white knight. And while the long-standing flirtation between Lupin and Fujiko continues, she is no longer his love interest nor are they quite so intimate as in the manga.

The loss of glamour doesn’t just affect Fujiko. An appreciation for the finer things in life vanishes as well. In The Mystery of Mamo, the gang enjoys good food, good wine, and classic cars that would make Clive Cussler and Dirk Pitt envious. The Castle of Cagliostro replaces these with a junker of a car, a gang that is closer to impoverished than flush with cash, and an inability to enjoy the fruits of their immoral labors. Lupin himself loses his own sophistication, beginning a long Flanderization into a buffoon. I can understand not wanting to promote the lawlessness of a thief, but the gentleman thief/phantom thief archetype that Lupin embodies requires sophistication, especially since his marks are millionaires and billionaires. And, like his grandfather, Maurice Leblanc’s Arsène Lupin, he has to fit in with high society and identify the countless fakes passed off on unwary buyers.

In later years, Miyazaki would decry the growing otaku-ization of the animation industry, including moe-ification of heroines. Ironically, with Castle of Cagliostro, by removing the more mature, sexual relationship between Lupin and Fujiko, he helped set the stage for the very trends he would later despise. It would take thirty years before the creative minds entrusted with the franchise would return to the glamour of the manga, starting with The Woman Called Fujiko Mine. Although not without growing pains, as the franchise is learning that brooding, sexual, and violent are not synonyms for mature and sophisticated. For the time being, though, The Mystery of Mamo is the closest a Lupin fan will get to the feel of an animated chapter of the manga.

I never touched on Fujiko in my Cagliostro review, mostly because she was such a small part of that movie – but as a major character in a popular franchise I can see how her sexless portrayal could influence anime negatively in the years to come.

Miyazaki does a much, much better job with female characters then on out, starting with Nausicaa onward.

I think the portrayal of Fujiko actually goes back to what I consider the biggest flaw of Cagliostro. Miyazaki obviously wasn’t comfortable with the character as created, and it showed; he shrank her role and completely neutered her sexually.

In later films, given the opportunity to create his own heroines, there’s a lot more subtlety and nuance. The closest we get to the glamorous Fujiko-type is Gina in “Porco Rosso”, who otherwise doesn’t have much in common.

(Sorry that I keep responding with Miyazaki factoids, but that’s my area of semi-expertise and I do find your articles interesting!)

-

Anthony

then what would’ve been your solution to the Fujiko conundrum of you had advised Miyazaki?

What was Fujiko’s original characterization in the original manga?

xavier-

That’s a complex question because it would probably involve some shifting of the overall plot in what is a fairly tightly plotted story. Mostly I’d say he should hold his nose and keep Fujiko’s glamour girl style. That is the character, however much Miyazaki dislikes it.

Because Miyazaki doesn’t use Fujiko all that much in the film it’s not a huge flaw.

-

Pardon me but I think you sell this film way too short. This is a film that deeply probes it’s characters and their complex relationships.

For example, consider the chief mentioning Zenigata’s daughter Toshiko. That said everything about Zenigata’s obsession with Lupin. He sees Lupin as the son he never had. He wants to punish Lupin like a father punishes a naughty child. Also, recall what Mamo showed Fujiko when they peaked inside Lupin’s mind. He thinks about Zenigata constantly and once again, a deceptively simple moment reveals Lupin’s motives. He steals and makes a spectacle out of himself because he is trying to get the attention of the father that ignored him. He remains a child because no one taught him how to be a man.

Jigen and Goemon, I think, are lost souls. They both choose to hold the world at arm’s length. Jigen was hurt a long time ago and he trusts practically no one except Lupin. Goemon is lives in a world that he can’t understand or identify with. He is engaged in a never ending quest to find himself.

As for Fujiko, I think we can both agree that she uses sex as a tool. She was hurt by a lot of men and she doesn’t trust them.

Last but not least there’s Mamo. He reeks of Bond villian cliches but there’s something pathetic about him. He is a lonely wretch who has a genuine appreciation for beauty. Remember that he was so desperate for Fujiko’s affection that he was willing to make Lupin immortal in order to please her. When Fujiko rejects Mamo, he sheds the last remnants of humanity. His body was the last remnant of his humanity.

So that’s my take on what the film did with the characters. The execution of the story was pretty much near perfection with the major highlight being the friction between all the major players. There is that problematic third act which had two climaxes but I think the ending makes up for it. These petty dictators could consume everything except love.