A Conversation with Scott Palter of West End Games

Thursday , 6, October 2016 Tabletop Games 4 CommentsNote: Scott owned the first incarnation of West End Games, but not the three that followed it. Also, while he is affiliated with Final Sword Productions and Under the Moon Books, he is semi-retired. His statements here are his own and do not reflect on any of these other entities.

—

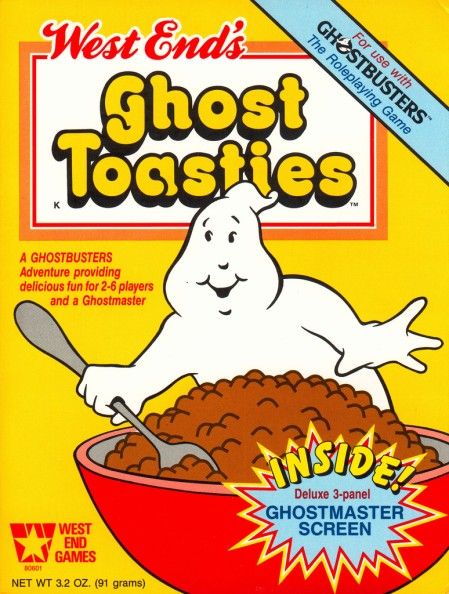

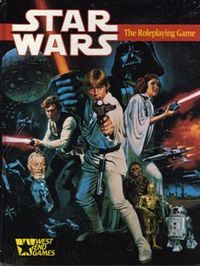

Jeffro: First off, let’s start with West End Games as a wargame company. As a child of the eighties, that is simply not how I see you guys at all! Fans of tabletop Star Trek games will of course be aware that you guys had the “not an rpg” license for mid-eighties movie Trek. Anybody that read Dragon magazine would know about the hilarious premise of many Paranoia adventures. Your d6 Star Wars rules are among the very short list of vintage rpgs that aren’t D&D that routinely get praised for their excellent design and playability. Finally, the Ghostbusters rpg gets a lot of attention for being so ahead of its time. You guys were synonymous with off beat science fiction themed games– the sort of thing that would be anathema to old school wargamers. To think that you guys could have been cut from the same cloth as SPI just blows my mind. Can you describe what the early days were like and how you ultimately came to the decision to change gears…?

Jeffro: First off, let’s start with West End Games as a wargame company. As a child of the eighties, that is simply not how I see you guys at all! Fans of tabletop Star Trek games will of course be aware that you guys had the “not an rpg” license for mid-eighties movie Trek. Anybody that read Dragon magazine would know about the hilarious premise of many Paranoia adventures. Your d6 Star Wars rules are among the very short list of vintage rpgs that aren’t D&D that routinely get praised for their excellent design and playability. Finally, the Ghostbusters rpg gets a lot of attention for being so ahead of its time. You guys were synonymous with off beat science fiction themed games– the sort of thing that would be anathema to old school wargamers. To think that you guys could have been cut from the same cloth as SPI just blows my mind. Can you describe what the early days were like and how you ultimately came to the decision to change gears…?

Scott Palter: We were a wargame company because I was a war game geek. A prior company I had playtested and designed for– Morningside– went belly up. It left a pair of finished but unpublished games, one mine and the other one I had done a bit of work on. I had a few bucks from my day job and teamed up with the remaining partner to publish. We got the name “West End Games” because the late night meet where we finalized the deal was at the West End bar near Colombia University. Between the four of us– 2 partners and 2 girl friends– we shot down every other name and I had to file as something. It went from there.

We got into rolelaying because Paranoia was kicking around looking for a home. The designers were in our extended social and playtesting circle. I wasn’t much into RPG’s due to an insane travel and work schedule from my main gig in fashion shoe imports. However I appreciated the humor and took a chance. It worked. Made a modest profit. So we did Ghostbusters. Made a modest profit and the wargame biz had fallen off a cliff. West End Games was supposed to be a side biz, not a money pit. So I rolled the bones on Star Wars.

I was always better at getting quality design work than I was at marketing, hence my fascination with licensing. I saw fantasy as covered by D&D. Traveller was there, but the universe didn’t excite me. Star Wars was the best universe out there. So I spent the money and we did it.

Jeffro: The early role-playing games like original Dungeons & Dragons, Traveller, Tunnels & Trolls, and Gamma World were put together from bits and pieces looted from a couple dozen fantasy and science fiction writers. They represented sort of a Frankenstein’s monster or kitchen sink approach to their respective genres. That’s not at all how people tend to do things today… but going into the eighties, it wasn’t obvious that things would necessarily change like they have. For instance, Kevin Sembieda says he wanted Palladium Fantasy (1983) to have a more unique setting associated with it but was advised by distributors to make it as generic as possible instead. Heroes Unlimited (1984) didn’t really have a particular world associated with it, but was just a generic superhero game.

With your games, Paranoia (1984), Ghostbusters (1986), and Star Wars (1987), you had systems that were all hard wired to very specific settings. Did that seem risky to you at the time, or was the writing clearly on the wall by then with regards to the end of the old hodge podge approach…?

Scott Palter: I approached things from a board game/ war game background. Some were generic like Tactics II. Some were quite specific– 3rd Reich, for example. It all depended.

Paranoia was a flyer at humor. I was in love with the setting premise. It sold. Not blow you away numbers but healthy profit. OK. So to my mind RPG’s would sell. They were also less of a financial risk than board games. Cost less to create and MUCH less to print 5,000 or so.

Ghostbusters was humor. So it was an obvious followon to Paranoia. It also had a known brand. We didn’t have to explain what it was to a distributor or a consumer. Again we made money. OK. That proved I was right and industry wisdom was wrong. Industry wisdom was that licenses didn’t sell. Public thought they were crap. Yes, many of them were but that wasn’t my approach. My approach was quality product. The license cost was marketing/branding. You still had to do first rate product – writing, playtesting, editing, art, layout. But the name bought you an audience that would try the first product. Hence betting a VERY large amount of money on Star Wars. Space Opera was a smaller market than fantasy but the niche to my mind wasn’t well filled by Traveller. Star Wars was even at ten years old the best known, most loved name. The trilogy was still all over cable TV so people kept seeing it. Even kids too young to have caught it in theaters.

Ghostbusters was humor. So it was an obvious followon to Paranoia. It also had a known brand. We didn’t have to explain what it was to a distributor or a consumer. Again we made money. OK. That proved I was right and industry wisdom was wrong. Industry wisdom was that licenses didn’t sell. Public thought they were crap. Yes, many of them were but that wasn’t my approach. My approach was quality product. The license cost was marketing/branding. You still had to do first rate product – writing, playtesting, editing, art, layout. But the name bought you an audience that would try the first product. Hence betting a VERY large amount of money on Star Wars. Space Opera was a smaller market than fantasy but the niche to my mind wasn’t well filled by Traveller. Star Wars was even at ten years old the best known, most loved name. The trilogy was still all over cable TV so people kept seeing it. Even kids too young to have caught it in theaters.

Besides, having a set universe never kept players from changing it with table rules. From consumer feedback most of them did. (The literalists on setting were the Paranoia fans.) So to me the known setting was a feature not a bug…and the consumers agreed. The initial sales of the two hard covers was explosive.

Jeffro: Well with Traveller, you had people picking up the game in the seventies and then going off and playing Alan Dean Foster’s Humanx setting or Jack Vance’s Planet of Adventure. I think it really was a generic space game that captured what people expected the genre to be like at the time, but by the eighties you would have had whole swaths of teenagers that had never read anything by H. Beam Piper, E. C. Tubb, or Poul Anderson. The assumptions about how science fiction should even work shifted dramatically over the course of about ten years there… and you even had the chance to flesh out the universe that was already in peoples’ heads…!

Given that there just wasn’t a whole lot of Star Wars themed media at the time– the whole Extended Universe books wouldn’t take off until 1991– you guys really were right in the middle of a huge change in how science fiction was even done. Were you all cognizant of just how big of an impact you were going to have at the time…?

Scott Palter: Hasbro had sat on the Star Wars merchandising rights for roughly a decade. We and half a dozen other companies put in bids as their rights expired. There wasn’t much merchandise– the Bantam novels were launched at about the same but didn’t go public till a tad later. What there was was endless repeats on the Movie Trilogy on HBO, USA, SCiFi etc.

Jeffro: Compare that to right now. In the game stores alone there is the tabletop star-fighter combat game (ie, X-Wing), the naval scale combat game, (ie, Star Wars: Armada) and it looks like three separate rpg lines (Edge of Empire, Age of Rebellion, and Force & Destiny) — and all of this is covering the classic “original trilogy” setting that was languishing at the time you made that bid. What is it about that setting that is the key to its enduring appeal…?

Scott Palter: 1. Paramount botched Trek licensing, repeatedly. They were impossible to deal with.

2. The movies never die, so people don’t forget them. Even the idiot prequels show multiple times per year on the various movie channels.

3. Old adage – if it has wizards and magic swords its fantasy. If it has space ships and blasters its space opera. If it has all four its Star Wars. Star Wars is science fantasy not hard science. Pushes more buttons on more people. Plus the whole universe works for gaming. No idiot Prime Directive. Its wild adventure and a small ship [Millennium Falcon] with a small crew can do vast things. There are clear heroes and villains. Lucas was a devote of old 30’s two fisted adventure. The critics may think it is jejune. Audiences love it when done well. We used a mantra in our design – cinematic realism. Your party should be able to do the things you saw on the big screen. Don’t let hard science, hard logic or anything get in the way. Live the Dream!

Jeffro: We’re talking about several decades worth of science fiction and game design here. What are some of the most common misconceptions that you see on these topics that your insider perspective would shed the most light on…?

Jeffro: We’re talking about several decades worth of science fiction and game design here. What are some of the most common misconceptions that you see on these topics that your insider perspective would shed the most light on…?

Scott Palter: That people really want to play out their media and comic book fantasies. Yes there is a market for generic worlds but there is a large one for worlds that already excite the imagination.

‘Cinematic realism’ matters. The less the rules make you think of them as rules/game the better. You should be doing scenes from the movie with yourself as the hero or villain. The rules work if they keep you ‘in the moment’ living the dream. They work if the end result at the table feels like an episode of the movie or show. Every time you have to come out of that dream to figure odds and minimax is a failure.

New editions of rules should be backwards compatible. Your player base has invested many dollars and much of their leisure time on dozens of books you publish for Star Wars or Ghostbusters or…they resent bitterly being told they MUST buy it all brand new. There should be a free upgrade sheet with the key changes. Many will buy the new books anyway, eventually. But new editions used as a revenue generator buildup ill will.

That the greatest danger for any publishing house is the ‘famous game designer trap’. Whifty new rules sets of finely written words that result in your half dozen best buddies (all industry pros) buying you a beer at Gencon saying ‘way kewl man!” We are publishing for average consumers– age range mid teens to mid 30’s – above that they may still buy books as collectors but the gaming groups start to break up. They want to have fun. Empower the players. A rules set isn’t broken because the most fanatic 2% can break it. That 2% is quite fanatic and often quite loud about it. The mass of your consumer base does not want a ton of complexity getting in the way of enjoying the gaming experience.

Jeffro: You know… I probably wouldn’t be covering role-playing games to the extent that I had had Wizards of the Coast not angered so many people with 4th edition D&D. The pushback was so vigorous, you had people rolling things back to some iteration of 1980’s style Basic D&D in droves…!

I got in touch with you because I’d heard you’d commented on one of my articles— the one asserting that the split off of gamers from traditional science fiction and fantasy fandom caused a brain drain from written sff that accelerated both its ideological homogenization and its fall to a secondary or even tertiary status as far as peoples’ imaginations are concerned. Could you share your perspective as in industry insider on that topic…?

Scott Palter: So that I don’t repeat myself, did Bryan pass along my original reply?

Jeffro: Here it is in its original form:

Actually correct but for the wrong reasons. There was a sea change but not the one the article says.

1. D+D for fantasy and Star Trek for SF essentially ate the B list shelf space in the book stores. This snowballed as more and more media properties [Star wars, Bab 5, Buffy etc.] started having multibook companion lines.

2. Newstands imploded and took the bulk of the market for the pulp short fiction mags with it. Magazines migrated to chain store shelves from newstands and the weird physical SIZE of the pulps made them difficult merchandise. Where they belonged was as anthologies on the BOOK shelves but…#tradition.

3. We then had a revolution that wiped out the bulk of the rack jobbers that out revolving book shelves in groceries, drug stores etc. The product kept selling. The jobbers failed as a business model [thefts and bankruptcy]and for a variety of silly reasons no one took their place. The big non-silly reason was the rise of Walmart. Walmart mostly leased their book and magazine space and prioritized family friendly over profitability. So the lessees tended to play it safe and buy the branded goods [Star Trek, Buffy etc.] instead of publisher B list.

4. An endless round of Manhattan publishing mergers kept incentivizing pubs to cut newbies and B list for sure things. Go to the stirling archives. We had some dandy threads on this. Short form. Old style publishing was a low margin gentleman’s biz. The megacorps bought these up and then wanted ROI.

5. Where RPG’s had an effect was at the margins – the adventures included flash fiction. They were vastly expanding the genre market but for pulp style stories at the exact moment [New Wave] when the pros fled from the pulp style to higher literary forms and academic prestige.

I can keep going on this if anyone is interested.

I’m interested!!

You’re mainly talking there about changes in product lines, mediums, shelving, distribution and so forth. What I was pointing out were differences between gaming and gaming-related scene versus what went on at, say, short story magazines like Asimov’s and Analog and publishing in general. Would you agree that there are two very different cultures there which both have their source in the older science fiction and fantasy fandom…?

Scott Palter: Yes but not exactly.

Scott Palter: Yes but not exactly.

Go back to 1970. The SF mags were the main source for genre fiction. There simply wasn’t much published as entire books.

Now zoom ahead to 1990. There was a flood of B list novels– DnD, Battletech, Star Trek, etc. There was a flood of RPG materials that included short fiction. In reverse, the points of sale for the magazines were vanishing. The problem wasn’t that Analog etc. couldn’t sell. The loss of news stands and small soda shops meant they became MUCH harder to find at the exact same point that B list genre action fiction became much easier to find. So a lot of readers and their dollars migrated. Any clearer?

Jeffro: But I’m not talking about why Analog could or could not sell. I’m talking about the culture at places like that. For instance, the literary antecedents to stuff like Traveller and BattleTech are in magazines. Jerry Pournelle’s “A Spaceship for the King” is an example of that. It appeared in Analog from 1971 to 1972. Zooming to 1990, it gets noticeably harder to find stories in that vein in the top tier fantasy and science fiction magazines. Gaming in general has much in common with pre-1980 science fiction and fantasy publishing. Today you pick up Asimov’s and you’re liable to see something more like “No Placeholder for You My Love”. Do you see what I mean…?

Scott Palter: Please see #5 below. The pros (magazine and book) fled from their roots to new wave and from there to being serious lit with a conscious push towards ‘social justice’. Genre ‘grew up’. It became a thing of university studies programs rather than a literature attuned to readers. The whole Sad Puppies culture war is about that.

Jeffro: Right, so science fiction and fantasy from before 1980 was primarily meant to entertain. Tabletop gaming that features science fiction and fantasy is… primarily meant to entertain. That leaves written science fiction and fantasy in the hands of people that want more than anything else to be taken seriously by… I dunno… English majors, journalists, and the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Do you think that the advent of tabletop role-playing caused a brain drain from the written science fiction and fantasy scene which would have exacerbated its decline?

Scott Palter: Actually it was the reverse. More people were getting professionally published writing genre because of table top gaming. Writing is a craft you mostly learn by doing. By radically increasing the size of the market, more people got the space to perfect their craft. The problem was that as genre publishing, Manhattan big corp style, got more serious in a literary sense, it didn’t recognize someone who had written a D&D novel or a TORG novel as a fellow writer. There was a social barrier against ‘those people’ which is funny really. The route to getting Manhattan published was increasingly via writers workshops instead of building a following of actual consumers. The entry to the field became a self-referential game divorced from saleability. The exception of course was Baen Books but Baen is treated as a pariah.

Jeffro: So with Michael Stackpole coming out of Tunnels & Trolls, Aaron Allston coming out of Champions and Car Wars, and David Weber coming out of Starfire… it’s more like gaming provided the space for a whole wave of authors to gain the skills they needed to go out and write the sort of books that “real writers” were no longer being directed to create. But this sort of unforgiving market pressure is almost identical to what magazines like Weird Tales and Planet Stories faced. The “writer workshop” crowd are thus doubly divorced from the roots of fantasy and science fiction. And that explains why to a growing number of people, their stuff doesn’t really even register as even being fantasy or science fiction.

Scott Palter: Pretty much.

Scott Palter: Pretty much.

Stackpole wrote for West End Games in the Star Wars Adventure Journal.

Allston worked on the Ghostbusters line.

Jean Rabe went from our stuff to being a successful genre author.

Timothy Zahn likewise wrote for us a bit.

The whole university degree / writers workshop world tries to make genre into highbrow ‘literature’.

Jeffro: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk to me about all this. Is there anything else you would like to add…?

Scott Palter: I would add one big thing. Tabletop gaming and its larger spinoffs– ie, Magic the Gathering and electronic gaming– mainstreamed the vocabulary of genre in ways that the old ghettoized print fiction world never did. Prior to all this genre fiction was an acquired taste with its own unique vocabulary, plot lines etc. ‘Normal people’ didn’t know where to begin, the magic words etc. Time travel paradoxes for example. Now the bulk of the population groks faster than light, lasers, hit points, magic systems, etc. Hollywood’s biggest movies are genre or comic books– genre from a different direction. The sad part is that the Manhattan publishing world has fled from this and refuses to write for this vast new market. So we have a world packed with branded novels– D&D, Star Trek, Star Wars, Buffy etc.– while the mainstream Manhattan houses have ever smaller print runs and shrinking advances. Pathetic.

My sum up is that West End Games’s failure was purely mine. If I hadn’t had my head VERY far up my ass for various personal reasons in the mid to late 90’s we would have survived the Magic tsunami just fine. We had a great creative team. My own personal failings killed the company. Sad but we all have our crosses to bear. If I were to have a tombstone the final words I would ask for were the games I helped bring to market – Paranoia, Star Wars (especially 2nd edition), Attack Vector Tactical and the launch I helped give to various creatives including Ken Burnside and Terri Pray.

Jeffro: Thanks again. This has been awesome!

Great Interview. Always loved D6 Star Wars. Never liked Paranoia or Ghostbusters. I would like to hear more roundabout the time of West End losing the SW license and such. I wonder how did the Magic tsunami kill West End? I know locally that it only helped game stores that embraced it and they sold more RPG’s because of it overall.

Fascinating stuff. “Cinematic realism” might not always be the best approach; I’ve always heard that the d6 Star Wars game was too easy on the Jedi. I haven’t played it in enough years to vouch for that first hand.

That said, it’s got to be better than the careful tactical positioning game of d20. That always failed to feel anything at all like the free-wheeling swashbuckling combat of Star Wars to me.

His comments on the fiction publishing scene are especially fascinating. I suspect he’s probably right, although (to the degree that they wished to do so) I wonder how many game fiction authors were ever able to “graduate” to “real” fiction.

Great interview!

I’d always wanted to check out the Star Wars d6, but the folks playing it at the FLGS when I was a kid usually had more ninja hookers in their games than a Frank Miller comic.

[…] In 1974, West End Games was founded late one night in a campus bar near Columbia University. It rose out of the smoldering embers of a wargaming company called Morningside, based out of the Morningside area, that went “belly-up” and left behind a number of talented designers with an interest in seeing their work find a home. As one of the company founders, Scott Palter puts it: […]