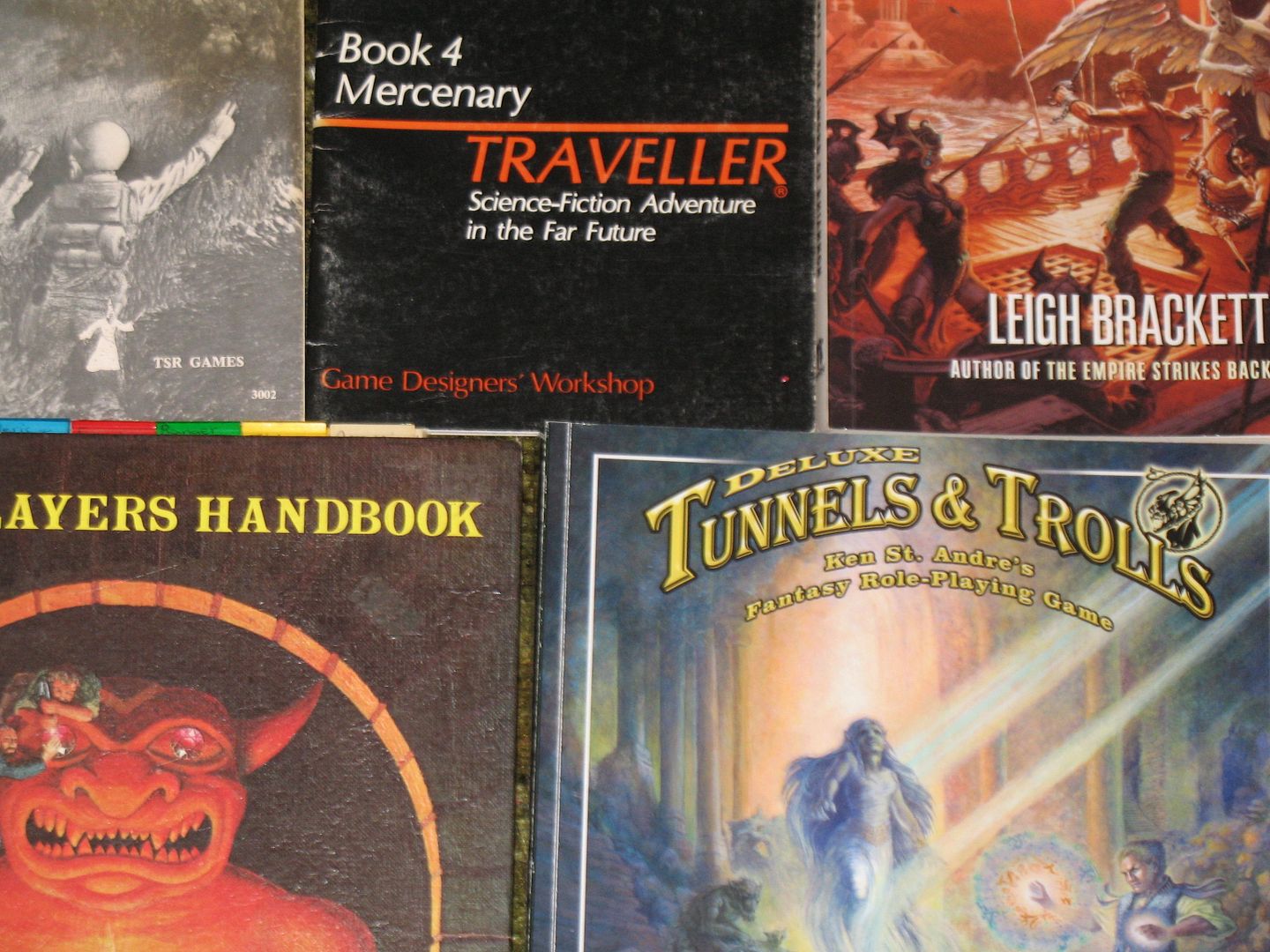

The authors of Appendix N had a far greater impact on the design of D&D than they get credit for. The scope of Andre Norton’s influence even spilled over into Tunnels & Trolls, Gamma World and Traveller, but the debt that gaming owes her is largely unrecognized. Far from gaining an appreciation for the roots of the hobby, a lot of people coming at the old games after the seventies and the early eighties instead saw something that looked to them as being outright broken. And by 1990 or so, a new generation unfamiliar with the old pulp stories would have largely been unable to appreciate the fact that the older games could allow you to play virtually anything from the classic works of fantasy and science fiction.

The authors of Appendix N had a far greater impact on the design of D&D than they get credit for. The scope of Andre Norton’s influence even spilled over into Tunnels & Trolls, Gamma World and Traveller, but the debt that gaming owes her is largely unrecognized. Far from gaining an appreciation for the roots of the hobby, a lot of people coming at the old games after the seventies and the early eighties instead saw something that looked to them as being outright broken. And by 1990 or so, a new generation unfamiliar with the old pulp stories would have largely been unable to appreciate the fact that the older games could allow you to play virtually anything from the classic works of fantasy and science fiction.

It wasn’t just that rpg creators had a large incentive to develop sprawling self-contained settings and supplements hard wired to support them. The transition from pulp and new wave fantasy to the pink slime of the eighties meant that not only had peoples’ expectations regarding world building changed, but expectation regarding things like characterization and plot diverged as well. An entirely new genre called “fantasy” emerged practically overnight blotting out the old canon on the basis of sheer volume as much as anything else.

The fact is, the style of those bloated and interminable fantasy epics is unlike anything that the first generation of role-playing game designers would have had in mind when they sat down to guide players on their first adventures at the tabletop. Consequently, if you’ve struggled with running the old games, chances are part of it is due to a mismatch between your genre expectations and the assumptions the designers were making. Just as one example, people coming to Traveller expecting the science fiction to be more or less like what they saw in Star Wars and Star Trek movies were necessarily going to face an uphill struggle. The novice Gamma World referee that had never read Andre Norton or Sterling Lanier is liable to be downright lost. The fact that these games often seem so inscrutable and unplayable to the uninitiated is because they are not in fact standalone games. They are supplements to the entire canon of classic fantasy and science fiction that came before them!

A lot of people have sat down at the table and tried to make these games play out more like the more recent phone book sized “epic fantasies”. This is a disaster more often than not as any player that’s complained of their game master’s railroading could tell you. Adventures for role-playing games have radically different requirements as as Pathfinder’s F. Wesley Schneider explains:

A major appeal of roleplaying games is that, as a player, your character can be anything and do anything — which is pretty much a nightmare for narrative. Working on an RPG adventure is like writing a story, but having no control of what the main characters are going to do, forcing you to anticipate character action and chart out the likeliest choices. Then, as if that wasn’t challenging enough, the writer isn’t conveying the story to the audience — that’s the Game Master’s job. So, you’re providing an elaborate, branching storyline that someone else narrates!

A side effect of this is that there’s actually very little in the modern fantasy epic that can be looted for a game session. In contrast to this, there’s very little that pulp author Leigh Bracket wrote that can’t be appropriated for a classic role playing game. Just take her story The Jewel of Bas as one example. A moderately experienced game master can practically run with it just moments after reading to the end!

Seriously, it’s got everything.

There’s a borderland: “All along the border countries they were saying the same thing. People who live or work along the edge of the Forbidden Plains have disappeared. Whole towns of them, sometimes.” (From D&D Module B2 to the Spinward Marches, this is where adventures have been set from the very beginning.)

There’s an awesome artifact: “But the Stone of Destiny—it’s a nice story, that one. A jewel of such power that owning it gives a man rule over the whole world….” (Hey, Tolkien had a point to make by setting Frodo on a quest to get rid of a fantastic artifact of supreme power. But that’s not how we tend to play these games!)

There’s a great lineup of monsters and heavies: “I keep thinking of the stories they used to tell—about Bas the Immortal, and his androids, and the gray beasts that served them.”

And for those of you that are tired of goblins and orcs, get out your monster manuals right now and add the Kalds: “They were no taller than Mouse, but thick and muscular, built like men. Gray animal fur grew on them like the body-hair of a hairy man, lengthening into a coarse mane over the skull. Where the skin showed it was gray and wrinkled and tough. Their faces were flat, with black animal nose-buttons. They had sharp teeth, gray with a bright, healthy grayness. Their eyes were blood-pink, without whites or visible pupils.”

Magic items are de rigueur, of course: “The Kalds urged them on faster with the jewel-tipped wands. The hot opalescence of the tips struck Ciaran all at once. A jewel-fire that could shock a man to unconsciousness like the blow of a fist, just by touching.” (This is an essential part of the medium that runs through everything from Temple of the Frog to Expedition to Barrier Peaks to Where Chaos Reigns. If you’re worried about the impact on your campaign, you might consider putting a limited number of charges on those babies…!)

It all takes place on a positively fantastic far future: “Long, long ago people were supposed to have seen them. In the beginning, according to the legends, Bas the Immortal had lived in a distant place—a green world where there was only one huge sunball that rose and set regularly, where the sky was sometimes blue and sometimes black and silver, and where the horizon curved down. The manifest idiocy of all that still tickled people so they liked to hear songs about it.” (Good grief. This is a great setting for Gamma World. But I’m telling you, if you want to get into the proper mindset for an AD&D campaign… use this as a starting point!)

Best of all, people dress like Sean Connery did in Zardoz: “The man in front of him was huge, with a mane of red hair and cords of muscle on his back the size of Ciaran’s arm. He hadn’t a stitch on but a leather G-string.” (How can you not have fun at the table with that?!)

The difference between Leigh Brackett’s writing and the typical rpg supplement of today is stark. The latter too often leaves me with the feeling of wondering just what exactly I’m supposed to do with it. I don’t have to sift through piles of background information to collate hooks that can be used to flesh out encounters in actual play. Adventurers really don’t need the extraneous world building details of the mediocre Tolkien pastiche or the aspiring novelist. They need to know the quickest way to the action with as little preamble as possible. The pulps deliver that every single time– and the amount of work that it takes to translate it to the tabletop is less than what it’d take to get some fully developed adventure modules off the ground!

But there’s more to it than that. If you read the story, you might notice that Leigh Brackett references both Cimmerians and Hyperborea as if they are of a piece with her wild science fantasy continuity. In this she is of course following H. P. Lovecraft’s example. And it wasn’t just Gary Gygax’s idiosyncratic penchant for plundering practically everything in order to create a vast tapestry of pulp fantasy for players to romp across. Ken St. Andre, James Ward, and Marc Miller created settings that were specifically designed to allow for typical pulp scenarios to be dropped in practically anywhere. When they did that, they were in some sense continuing and building on a technique that writers like Leigh Brackett used to give their lean and mean pulp stories a sense of being part of something greater.

We’ve lost that. And when we let that go, we not only lost some of the playfulness that infused the classic role-playing games, we lost a good part of their playability as well. I think the best way to celebrate Leigh Brackett’s 100th birthday is to begin trying to reclaim that spirit from her works and to bring it to life again in all new role-playing adventures. It’s not how people tend to create settings and stories anymore, but it works. The fact that people are still playing the games that were designed this way even as their more focused competitors fade oblivion is a testament to that.

—

Thanks to Larry Richardson for assistance, suggestions, and feedback.

Nice post, Jeffro.

Strangely, or not so strangely, I’ve been working up a post on a similar theme this past week.

I had already linked another of your posts in mine. I’ll add this one too!

I’m linking to Maliszewski’s picaro post as well. He really did nail down lots of things!