Here is a guest post by Richard:

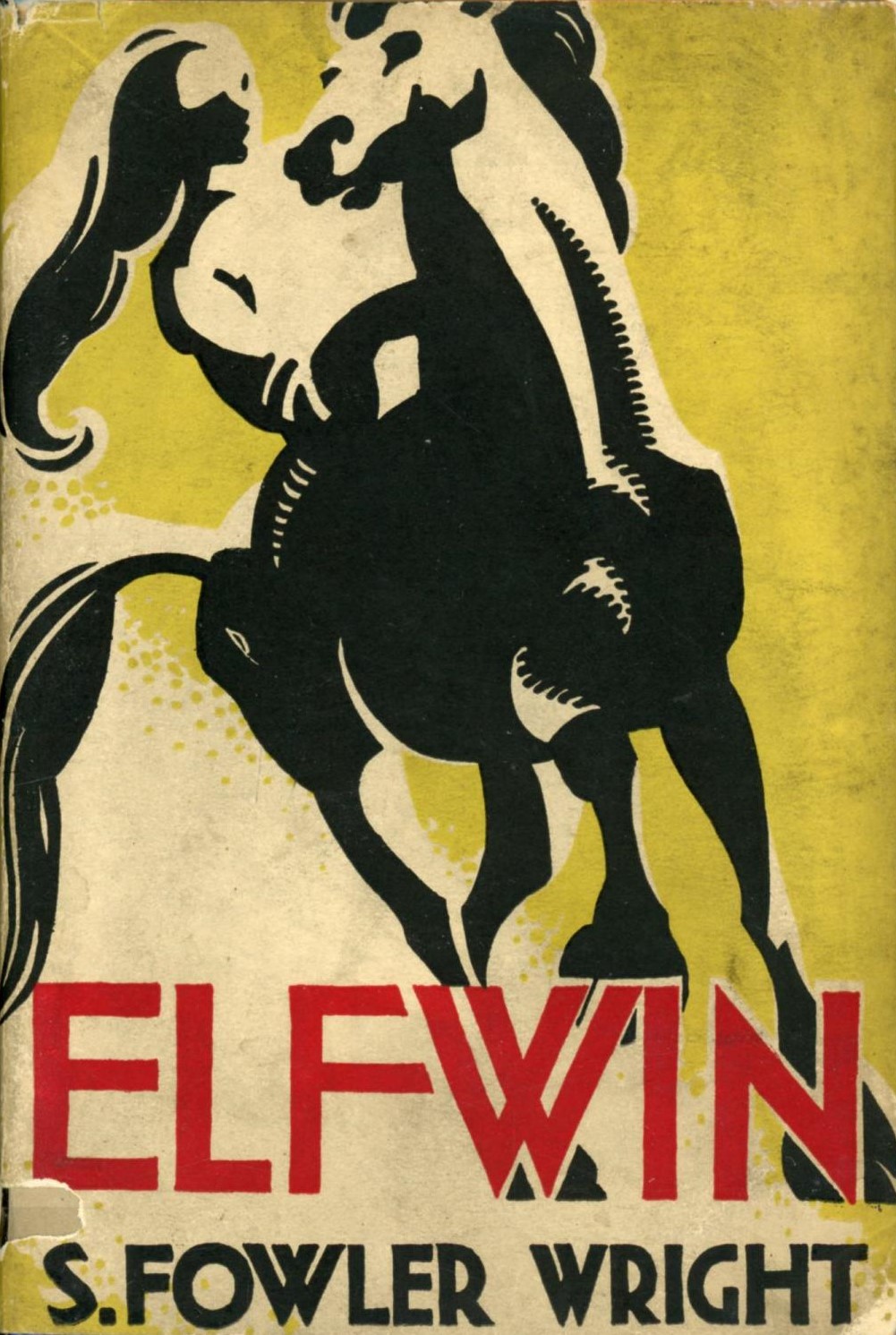

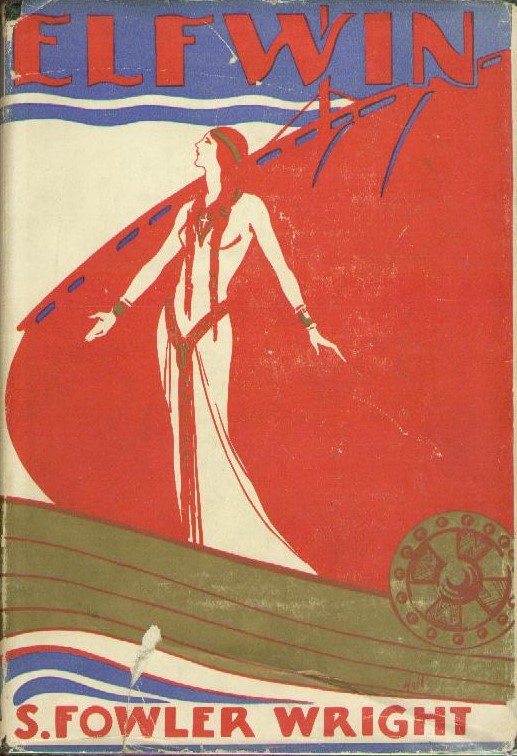

ELFWIN by S. Fowler Wright: A Review

By

Richard Toogood

The Anglo-Saxons have made something of a belated push for public recognition over recent years. Hitherto marginalised in favour of the doomed glamour of the Romano-Britons whom they supplanted, and the more tongue friendly named Normans that came after, the popular perception of them has been too long shaped by quaint folk tales concerning burnt cakes and naked horse rides.

Important archaeological discoveries however, such as the Staffordshire hoard in 2009, made global headlines and succeeded in shining a light on this often-overlooked yet remarkable culture. And the Anglo-Saxon cause hasn’t been hurt either by the success of Bernard Cornwell’s thirteen volume Warrior Chronicles and its associated tv adaptation. More recently attention has become focused on a unique Anglo-Saxon asset: Aethelflaed.

If there is another figure more apposite than she to the current cultural climatic flux, with its hagiographic veneration of everything female, then I’m sure I don’t know who qualifies. They certainly won’t be found among the Romano-Britons or the Normans for neither culture produced anyone to bear comparison with the Myrcna hlaedige.

She was a queen in everything but name. Someone who formulated military strategies and commanded armies in the field; who fortified and garrisoned towns; ordered punitive expeditions into the heartlands of her enemies; who rebuilt cities and commissioned the raising of minsters and churches. Probably the only thing she didn’t do was to sit astride a charger in a coif and helmet and cleave Vikings with her own hands: [wonderful though it is to imagine and as Angus McBride so memorably depicted her].

Taking all this into account only makes it the more surprising that she doesn’t feature more widely in popular culture. There is scant need here to reimagine and pervert an established female personage to satisfy an artificial and asinine contemporary imperative.

One novel in which she does feature prominently is ELFWIN, a 1930 historical romance written by Sydney Fowler Wright (1874-1965). Wright captured her charisma, cool tactical shrewdness, political acumen and decisive personality well enough. But this only makes some of the liberties he took with her character all the more unfortunate and inexplicable.

Nothing is more unfortunate and inexplicable about this novel though than the decision to subordinate a compelling figure like Aethelflaed in favour of her daughter, the titular Elfwin, a nebulous historical personage of no significance and about whom next to nothing is known. Granted it might have been this very lack of facts that commended Elfwin to Wright’s imagination. However, if she was even half as irritating, egotistical, exasperating, narcissistic, naïve, hypocritical, stupid and headstrong as Wright chose to depict her as being then her committal to historical oblivion is something for which everyone should be grateful.

The novel opens with Aethelflaed’s capture of Derby in AD917; a pivotal historical event but accomplished here in a manner that favours romantic melodrama over martial credibility and by so doing forewarns the reader of the path that the book will take. Events then play out against the backdrop of military offensives undertaken in concert with King Edward of Wessex, Aethelflaed’s brother, which in the fullness of time will result in the conquest of the Danelaw.

Such momentous events are utterly immaterial to the insufferable Elfwin though. She is completely besotted with Sithric, a Viking hostage at her mother’s court whom events have contrived to see elected king of Northumbria in absentia: [not to be confused with the real Sihtric of York who ended up marrying Athelstan’s sister before conveniently dying soon after]. Elfwin spends fully half the book treacherously orchestrating Sithric’s escape from custody, first from Gloucester and then in Derby. The second half of the novel then follows the woolly-headed heroine’s deluded attempt to avert the war which her own actions have precipitated. And quite how delivering herself into the hands of her mother’s enemies is supposed to achieve this defies comprehension much less explanation.

Elfwin is a ridiculous creation and completely unbelievable on just about every level. She shamelessly abuses her authority to browbeat and beguile stupid men into doing her bidding while abdicating herself of all sense of royal responsibility or duty. And every subordinate dumb enough to demonstrate loyalty to her she leads to their death. At one point she even knifes a lowlife in the back, thereby doing literally what she spends the majority of the book doing figuratively to her land and heritage.

One of Wright’s more absurd conceits is the mysterious back story he affords her which hints at her being illegitimate; the issue of an illicit congress between Aethelflaed and an unidentified someone of non-Saxon stock whom is preserved in her black hair and dreamy tree-hugging ways. Irrespective of the groundless calumny this directs against Aethelflaed’s propriety it also paints her as a hypocrite for objecting to Elfwin’s own consorting outside of her race. To make matters worse Wright even has Elfwin identifying herself as her mother’s “little sin”.

Bastardy was certainly rife in the courts of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, and Mercia was famously more female tolerant than anywhere in Britain at that time. But the idea of the pious daughter of Alfred the Great having it off in the woods with some Pictish swineherd or some such is ludicrous. And even if she had, does anyone seriously believe she would have encouraged stories of changelings by naming a baby that looks “like an elf” Elfwin? As commonplace as it was bastardy still had consequences in Anglo-Saxon royal circles as was demonstrated in the contested and contentious accession of Athelstan in AD924. An event the novel erroneously affords an air of formality.

And speaking of Athelstan; there is no character worse served by the book’s narrative contrivances than he for he isn’t afforded even a single line of dialogue with which either to defend or express himself. Sure, his ultimate greatness is acknowledged (via that irritating narrative technique of future knowledge conveyed by the omniscient narrator) but mostly he is referred to only in passing and usually in order to contrast his weaknesses with Elfwin’s perceived strengths. Even when he actually appears on stage, he is relegated to a mute horseman seen at a distance. It is a wretched and cavalier treatment of one of the most important figures in all of British history, let alone the Anglo-Saxon period specifically.

It needs to be conceded that this is a romance (in every sense) and not a historical novel proper, and so allowances must be made for the fast and loose way it plays with facts. Such as erecting stone castles where none ever existed and settling Greenland sixty years in advance of Erik the Red. It would be a lot easier to do this though if the fiction was even half as interesting as the actuality. The fact that it isn’t is entirely down to the wholly unlikeable and unsympathetic central character.

Take her out of proceedings and the book does boast some things to commend it. Not the least of these being the one-eyed Viking Bear Thorkeld, sometimes called Wave-watcher, who likes not war and dreams of exploring the uncharted seas of the west. All that is most engaging in the book comes courtesy of him, and he delivers all the best speeches in which it is tempting to discern Wright’s own views on gender roles and responsibilities. That said, Thorkeld’s quaint no-means-yes rape grateful philosophy probably won’t succeed in winning him many fans from amongst today’s readership.

Fowler Wright remains a significant, if now largely unread, figure in the history of British genre fiction. Books like THE AMPHIBIANS and THE ISLAND OF CAPTAIN SPARROW serve as bridges between the scientific romances of Wells and Griffith and the SF proper of Stapledon and Clarke. He also produced work in the future war category (THE WAR OF 1938), catastrophe novels such as DELUGE and timeslip/reincarnation fantasies (DREAM and its sequels). He even published stories in Weird Tales. The main bulk of his output however was in the field of detective fiction.

Reading ELFWIN one might be forgiven for concluding that its spirited/wilful/irresponsible heroine (reader’s preference) epitomised Wright’s sympathy towards female suffrage (barely a decade in the past at the time of the book’s completion) and support of emancipation. And perhaps it does. If so it cannot but fly in the face of his reputation as a reactionary who railed against totems of modernity such as the motor car. To say nothing of birth control.

Equally, it could be saying completely the opposite. You pay your money and you make your choice.

Anyone interested in either the personage of Aethelflaed or the period in which she lived might like to know that a 40th anniversary edition of Michael Wood’s IN SEARCH OF THE DARK AGES is now available.

This book, together with its associated tv films, was pivotal in stimulating my teenage interest in the Anglo-Saxons and is one I have returned to repeatedly over the years.

Now heavily revised, to incorporate the plethora of new discoveries unearthed since its original publication in 1981, Wood has taken the opportunity to insert additional chapters concerning figures not previously covered. One of whom is Aethelflaed.

The book remains a classic of popular history and is recommended unequivocally.