Galactic Humility – The Magic of Mistakes and Misdirection

Tuesday , 24, February 2015 Uncategorized 5 Comments“All my life I have been what is called a square. A very serious type of person. A slow thinker. I am one of those odd types who, lacking natural talent and having no natural intiuation – these are probably related phenomena – had to think my way through life.” — A.E. Van Vogt (from “Inventing New Worlds II,” originally presented at the 1979 Sperry Univac seminar on technology)

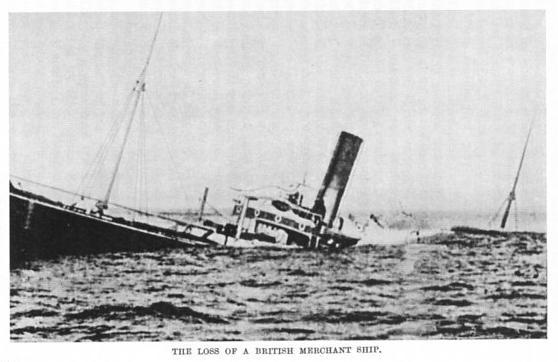

This was Science Fiction when Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote “Danger” in 1914.

As Jeffro’s article regarding demons and Gardner Fox demonstrates, an element of inspiration is the unexpected. I.F Clarke wrote that Arthur Conan Doyle’s preposterous notion expressed in the June 1914 short story “Danger” — that German submarines would disrupt shipping if England did not build a Channel tunnel — was dismissed by the future Commander in Chief, South Western Approaches that it “is inconceivable that any naval officer would ever sink an unarmed merchant vessel.” Within six months of Doyle’s story, the German navy was sinking merchant ships every day.

Clarke’s point however, was that Doyle’s prediction was not motivated by prophecy, but by advocacy. Doyle wanted to inspire a great engineering marvel: the Channel Tunnel, and he “lucked out” by guessing the future in the process.

That is the essence of the “wisdom” that hard science fiction offers to us: that in predicting or anticipating one technology or cultural ideal, science fiction is just as likely to point the reader in a new, unguessed direction. Science Fiction is the art of beneficial unintended consequences, and the important thing is for authors to be ambitious enough to predict badly, and humble enough to admit it. Somehow, that leaves space for real insight.

Van Vogt himself discovered something interesting when he sent out a sort of informal survey to about 450 science fiction writers in 1978. Most of those who wrote hard science fiction did not see themselves as innovators.

Arthur C. Clarke…”who is responsible for those fixed orbit ideas, wrote, ‘I can’t think of a single thing I ever did.'” – Van Vogt, recalling Clarke’s response to his letter.

In a different interview with Rex Malik, Arthur C. Clarke said, “You know, science fiction almost completely failed to predict the advent of the personal computer.”

After all, Doyle was wrong, by nearly a century, about the near-future Chunnel, but that didn’t stop his enthusiasm, or hinder the quality of “Danger.”

The author of science fiction must not be the sort who fears making mistakes. In fact, quite the opposite:

Leigh Brackett wrote in 1944 that “Perhaps you like scientific technological fiction (stf) and want to write it, but are scared off by the word ‘science.’ You’re no Ph.D., and aren’t likely to be, and you are thrown into a panic of inferiority by casual references to discontinuous functions in a four-dimensional space-time grid. Well, brother, you would be surprised how many top-notch stf writers don’t know any more about than you do.”

“You know that water must reach the “boiling point” before there is the desired chemical change in your potatoes. You know the water has to be pumped to your home because this planet’s gravity has a hold on it and insists that water seek the lowest level.

Thos things, and a hundred thousand more, you have proved by experiment and duly recorded in the notebook of your brain….

You can write science fiction if you want to.”

Ross Rocklynne, “Science Fiction Simplified” -1941

Van Vogt described his writing process like this:

“I worked out a system for writing. When I tell that to people they feel kind of stunned. My method of writing is probably different from that of other writers. I have no advance outline. In fact I couldn’t make one up. But none the less I use a systematic approach. But each new development in the plot, while implicit in the previous material, is as much of a surprise to me as I hope it will be to the reader.”

“The very first story I wrote, I wrote in 800 word scenes with five steps in each scene. It was about 9,000 words long and therefore it had about 1,000 sentences and each one of those sentences had emotion in it. One thousand sentences of emotion. It sold on the basis of that. Subsequently I decided that science fiction need a hang-up in every sentence. That is, it had to have a thing in it where the reader made a contribution. Years later I read Understanding Media by McLuhan and I discovered that he had a word for that kind of thing, it was ‘hot fiction’, like radio where the listener has to contribute a picture.”

I think that’s one of the remarkable things about so many of the greats of the past: they dispensed with the notion that hard science fiction is an act of intelligence.

Instead, they portray it as an act of the will. This isn’t to say that a Disneyfied “Anyone can write Science Fiction” concept is what they promoted. (See also, the recent Nebula Awards.) To the contrary: they argued that Science Fiction is a vocation to which few are called.

It is just that, if you are called, the hard science isn’t the thing that is going to stop you.

But pride might.

“Perhaps you like scientific technological fiction (stf) and want to write it, but are scared off by the word ‘science.’ You’re no Ph.D., and aren’t likely to be, and you are thrown into a panic of inferiority by casual references to discontinuous functions in a four-dimensional space-time grid. Well, brother, you would be surprised how many top-notch stf writers don’t know any more about than you do.”

And 95% of your readers will know even less than that.

So true. Look at Star Trek. The writers routinely ignored Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, and I think half of its audience cringed when Kirk talked about traveling to the “southernmost part of the galaxy.”

Nevertheless, the series inspired cell phones, tricorders, and now even transporting is being seriously researched. And the boost Star Trek gave spec fiction was enormous.

Yes, and I don’t think this is an excuse for writing lazy science, or that your story isn’t going to suffer if you are pig ignorant about some fundamentals to your own world. I think what Clarke and Van Vogt and all the others were pointing to was a discrediting of the theory that Science Fiction is dying because science is too complicated nowadays for the non-specialist.

Brackett, in fact, was saying quite the opposite: that the generalist has an advantage over the specialist in some ways. Doesn’t mean the generalist can tell Relativity to pound stand, but it also doesn’t mean that the generalist is somehow forced to take the Way of the Scalzi: the direct copying of masters in order to avoid offending the gods of science.

Then there’s this classic quote from Orson Welles:

“I didn’t know what you couldn’t do. I didn’t deliberately set out to invent anything. It just seemed to me, ‘Why not?’ There is a great gift that ignorance has to bring to anything, you know. That was the gift I brought to [Citizen] Kane… ignorance.”

Good post, thanks. Very heartening and even inspiring.