Guest Post by Misha Burnett: Tanith Lee’s Tales Of The Flat Earth

Monday , 18, January 2016 Appendix N, Appendix X 7 CommentsEditor’s note: I am pleased to be introducing Misha Burnett here at Castalia House. He is one of several “usual suspects” that have had a great deal to say in the many discussions about fantasy I’ve participated in the past few years. You can find more about his books and commentary over at his blog— and note that one of his stories will be appearing in Cirsova’s upcoming magazine. Welcome, Misha!

—

Cold Gods and Hot-Blooded Devils: Tanith Lee’s Tales Of The Flat Earth

Cold Gods and Hot-Blooded Devils: Tanith Lee’s Tales Of The Flat Earth

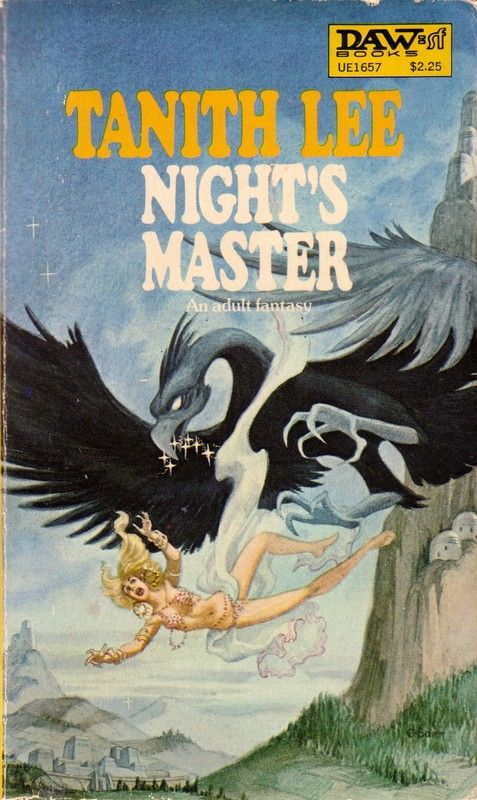

Recently I listened to Tanith Lee’s Tales Of The Flat Earth series, as read by Susan Duerden. The series is available on Audible.com, and I strongly recommend it—Susan Duerden’s voice acting is phenomenal, and well suited to the tone of the stories. For those who prefer their books as text, it seems that the series is out of print, although old copies are available. The Penguin Books website does promise that the first volume, Night’s Master, will be re-released as an e-book, scheduled for August of 2016. It is to be hoped that they will release the entire series—it is a sadly neglected classic of the fantasy genre.

The series consists of five books, Night’s Master (1978), Death’s Master (1979), Delusion’s Master (1981), Delusion’s Mistress (1986) and Night’s Sorceries (1986). Together they tell an epic fantasy story that stands out from the mainstream of fantasy (if there can be said to be such a thing) in a number of notable ways.

While Tolkien’s influence on the genre can hardly be overstated, Lee set out to create a universe not inspired by the Northern European legends that Tolkien used. Instead, she drew more on Middle Eastern, African, and Asian mythologies, blending them into a colorful and sensual world plagued by demons and monsters.

As the series title implies, the Earth was, in those times, literally flat; a plane with four corners and other Earths—Inner, Under, and Upper—above and below it. This cosmological construction rests on a sea of Chaos from which the Sun and Moon rise and sink each day. The lands have no relation to any modern continents. Judging by the settings of the collected tales, most of the Flat Earth seems to be desert, with a few seas and mountain ranges. This is hard to gauge, however, since the landscape changes over time and the time scale of the series is staggering.

This is because the main characters are the five Lords of Darkness, who are immortals. Most of the books are episodic in nature—the first and last in particular could be described as much as shared world collections of stories as individual novels—with the events of one section being referred to as legend by the ephemeral human characters of the next.

For example, Night’s Master opens with Ahzrarn, King of the Demons, taking a young mortal boy as his lover. Among other gifts that the Lord of Darkness bestows on the boy, Ahzrarn gives him a magic token, a silver whistle that will call the Lord. In the middle of the book, a human sorceress comes across a legend of that token and searches for where it lies, in order to summon Ahzrarn. Later on, this sorceress is herself referenced as a legend, with the significant details of her life misrepresented. This kind of hearkening back to earlier stories, always viewed through the distorting mirror of time, is part of what gives this series its charm.

One also learns that not even immortals can escape the consequences of their actions. Ahzrarn and his un-kindred—Uhlume, who is Lord Death, Chuz, who is Prince Madness, Kheshmet, who is Destiny, and the unnamed Fifth Lord—meddle in the affairs of mortals and in so doing weave the tangled nets in which they themselves are often caught.

In the end it is not the gods, who are shown as distant, uncaring beings possessed of vast power but disinclined to use it, or the Lords of Darkness, or the various races of demons who are the real heroes of the Flat Earth, but human beings.

Mortal men and women, weak, short-lived, foolish and fearful, throughout the series preform acts of great love and great cruelty and often show extraordinary courage, standing up against powers that they cannot comprehend or overcome. It is the human characters who show Lee’s particular brilliance. Even the walk-on characters—castle guards, merchants, prostitutes, stone masons—have a warmth and humanity that makes them real and in turn give the machinations of the Lords of Darkness power. We see glimpses of the human faces and human lives of those that they see as just pawns in their endless games. We care about the people, and that’s what makes us care about the world.

The overall style echoes (deliberately, one assumes) the Arabian A Thousand Nights And A Night, with nods to Aesop’s Fables and other classic literature, but with a Fractured Fairy Tales sensibility—never quite parody, but a healthy dose of irony. I found the books hard to put down (listening to them in my car I found excuses to take the long way home from work so I could finish a chapter) and I suspect that most readers of fantasy would as well.

—

Misha Burnett is the author of Catskinner’s Book, Cannibal Hearts, The Worms Of Heaven, and Gingerbread Wolves, modern fantasy novels collectively known as The Book Of Lost Doors.

When Azhriaz has her worshippers cutting off their own hands and murdering their families as offerings to her I put down the series.

Excellent writer, exotic and beautiful prose, but she glorifies evil as glamorous too much for my tastes. I’ve read many other of her books, and many have the same thread running through them to a lesser extent.

The New Wave movement did embrace a certain moral ambiguity, I suspect as a reaction against what some saw as a simplistic black and white morality of the pulp fiction of the 40s and 50s. A lot of writers took the opportunity to delve fairly deeply into the anti-hero trope and often into an outright celebration of villainy.

Welcome, Misha. Tanith Lee is one of my favorite writers and Tales of the Flat Earth are one of my all-time favorite series.

I see her portrayal of evil as being one of the very best in fantasy. Evil can be glamorous. Evil is tempting. Evil is seductive. As it has been said, if you don’t think sin is fun, you’re not doing it right.

That’s why it is so hard to fight against it; even the Apostle Paul addressed this issue.

That sounds pretty rad. When I reactivate my Audible account this’ll be my first pick.