Guest Post: Will the Last of King Harold’s Housecarles Please Form an Orderly Queue

Saturday , 2, December 2017 Uncategorized, War 5 CommentsWill the Last of King Harold’s Housecarles Please Form an Orderly Queue

By

Richard Toogood

It doesn’t require a p articularly robust grasp of the past to recognise and understand the significance of the year 1066. It is one of the most famous dates in history. The year of the three kings and the three battles. It bore witness to the Norman Conquest of England and by so doing laid the foundations of Great Britain. Equally significantly, by reorienting the political compass of England away from Scandinavia towards the continental mainland it is no exaggeration to say that it had profound ramifications for the entire course of European history, ramifications which extend right up to the present day.

articularly robust grasp of the past to recognise and understand the significance of the year 1066. It is one of the most famous dates in history. The year of the three kings and the three battles. It bore witness to the Norman Conquest of England and by so doing laid the foundations of Great Britain. Equally significantly, by reorienting the political compass of England away from Scandinavia towards the continental mainland it is no exaggeration to say that it had profound ramifications for the entire course of European history, ramifications which extend right up to the present day.

The story of 1066 then is one of monumental events directed by personages of mythic proportions. It defies understanding that Hollywood has never cottoned onto it: Game of Thrones has got nothing on this epic.

But if the film and TV establishments have been negligent in their appreciation of the story’s dramatic appeal then the publishing world has scarcely registered anything better. The number of novels that have drawn creditably upon the story is minimal. Particularly when compared with the tsunami of Arthurian fiction that has washed across the publishing landscape over the years.

Whether one sees the Norman Conquest as the triumph of progress over stagnation or a cultural apocalypse is a matter of personal choice. It is fair to say that both views have retained their power to incite a violent reaction over many centuries. The disenfranchised and the downtrodden have traditionally apportioned the blame for their grievances to the Norman yoke. The disgruntled Levellers, for example, made great play over the point in the aftermath of the English Civil War. For the elite, those privileged descendants of William the Bastard’s triumphant colonels who profited most from the spoils of the Conquest, it was only Norman energy, innovation and ambition that took a bucolic backwater of a country out of the Dark Ages. The Norman Conquest has been the subject of diametrically opposed spins from the moment the first thread was stitched into the Bayeux Tapestry.

It was the Victorians who rediscovered a source of pride in their Anglo-Saxon roots. They it was who erected statues of Alfred the Great, all but venerating him as the architect of British liberties. But the Victorians could not fail to be conflicted in their feelings about the consequences of the Conquest. It is difficult to lament the lost freedoms of an imaginary Anglo-Saxon utopia when one is engaged in the process of an imperialist project of global extent. The compromise they came to was to attribute the success enjoyed in their own times to the amalgam of stoical Anglo-Saxon fortitude with ruthless Norman gusto. In effect what they were saying was that the ruins of Anglo-Saxon England were the necessary foundation only upon which could a greater Britain be built.

This is one of the key inferences which one may draw from Sir Walter Scott’s influential IVANHOE (1820) with its Saxon hero happily committed to service in the retinue of a Norman king. Scott was of course equally committed to the cause of Scottish/English unionism and so was subtly drawing parallels to advance that agenda. Scott’s view was endorsed by later writers such as Charles Kingsley in HEREWARD THE WAKE (1866) and George Henty in WULF THE SAXON (1895), which likewise championed the Anglo-Saxon cause whilst wedded to the idea of the greater Norman good.

One of the more interesting conceits that found favour in Conquest fiction of the 20th century was the idea that Harold Godwinson didn’t actually perish on the field of Hastings but instead survived to pursue a variety of fictional afterlives. This is an idea which actually goes all the way back to a medieval manuscript called the Vita Haroldi. Rudyard Kipling was among the first to utilise this idea, painting a very sympathetic and poignant portrait of the tragic Harold in “The Tree of Justice”, one of his enchanting Puck stories collected in REWARDS AND FAIRIES (1910). Robert E Howard, not a writer exactly renowned for harbouring Saxon sympathies, was equally impressed enough by Harold’s fighting spirit to likewise whisk him away from the carnage of Hastings and repatriate him to Outremer fighting Saracens in the rip roaring “The Road of Azrael”.

Interest in the subject appeared to drain away as the century progressed. It may be supposed that with Britain twice facing the serious possibility of invasion during the first half of the 20th century there wasn’t much of an appetite for being reminded of the last time such an enterprise had actually succeeded. Later years however saw the publication of books as diverse as Noel Gerson’s THE CONQUEROR’S WIFE (1957), Brenda Honeyman’s HAROLD OF THE ENGLISH (1979), John Wingate’s WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR (1983) and Helen Hollick’s HAROLD THE KING (2000).

Interest in the subject appeared to drain away as the century progressed. It may be supposed that with Britain twice facing the serious possibility of invasion during the first half of the 20th century there wasn’t much of an appetite for being reminded of the last time such an enterprise had actually succeeded. Later years however saw the publication of books as diverse as Noel Gerson’s THE CONQUEROR’S WIFE (1957), Brenda Honeyman’s HAROLD OF THE ENGLISH (1979), John Wingate’s WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR (1983) and Helen Hollick’s HAROLD THE KING (2000).

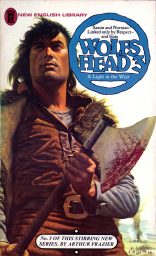

Quite possibly the most successful conceit to have arisen out of Conquest fiction is the employment of a character claiming to be King Harold’s last surviving housecarle. Housecarles were professional warriors bound by solemn oaths not to outlive their lord on the field of battle. To do so was a mark of the deepest shame and therefore not something anyone in that position was ever likely to own up to. Nevertheless this is one of the premises of Laurence Brown’s HOUSECARL (2001). Another “last” housecarle called Bovi pops up in George Shipway’s brilliant KNIGHT IN ANARCHY (1969). A similar contention underpins Ken Bulmer’s six volume WOLFSHEAD series (1973-1975). Undoubtedly the most commercially successful of these survivors is Walt, hero of Julian Rathbone’s gimmicky yet nonetheless spellbinding THE LAST ENGLISH KING (1997).

As the years begin to count down towards the 1000th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings it is probably fair to say that the Saxon cause seems to be coming into the ascendancy. So much so that James Aitcheson’s recent pro Norman Tancred trilogy seems painfully naive and old fashioned. The ludicrous portrayal of the Saxon hero Edric the Wild found in THE SPLINTERED KINGDOM (2012) little removed from a churlish caricature.

The Battle of Hastings was a close run thing. Had it been fought even a week later, and darkness fallen that much sooner, the probability is that the result would have been completely different. The irony of that is, had that been the case, then  the chances are it is a battle that would not now be remembered at all.

the chances are it is a battle that would not now be remembered at all.

The always underappreciated Stephen Lawhead wrote a series called the King Raven trilogy essentially about the Welsh response to the Norman conquest. A Robin Hood retelling and an awesome series.

A fine post, Richard! I did a college term paper on 1066. It was a “What If?” history elective. I had Hardraada not dilly-dally about taking his Yorkish hostages — as he uncharacteristically DID in our timeline –and thus be on a different footing with no Battle of Stamford Bridge. Harold and Harald worked something out and the Bastard was caught in a by-land-and-sea pincer attack.

I posited a fairly rosy picture of the history going forward from that, but I doubt it now. A major Norman setback such as I envisioned — Harold helping Hardraada take Normandy in exchange for Harald giving up his claim on England –would have been cataclysmic for Europe as a whole. The Normans were quite simply the fiercest and most dynamic people in Christendom during that crucial period. Without the knock-on effects of their actions all over Europe and the Levant, most of Europe might have been Mohammedan by 1600.

That said, the English possessed an admirable society on the eve of the Conquest and Harold was the most decent of the “three kings.” He got dealt a crap hand.

-

Hello,

Do you still happen to have that “What if” scenario college paper? If so, I’d love to read it. Perhaps you can share it?

I’m curious does anyone else know of any Pro-Union Novels other than Ivanhoe, Hereward the Wake, and Wulf the Saxon?

It’s always interesting how conflicted the Brits are towards the Normans. Looking back, the Normans did Britan and Europe a big favour. The medieval Brits have always been a positive influence and helped Europe become great.

My only regret is Henry’s revolt when he broke from the church and created a eratz caliphiate in England.

And both England and Europe suffered since

xavier