Rampant Coyote has yet another account of how what he’d heard about the pulps just didn’t stack up to his own reading experiences:

Rampant Coyote has yet another account of how what he’d heard about the pulps just didn’t stack up to his own reading experiences:

As I first started digging into the history of the pulps, the story I heard was that these were a training ground for genre fiction writers. They got their start in the pulps, and then as they got better, they “leveled up” into bigger and better markets. Which sounded cool, until I realized that a lot of my favorite older stories were originally from the pulps. By implication, this suggests that the pulps were the place for the lesser quality fiction, and that I am a reader of highly questionable taste.

The latter part may very well be true, but the first isn’t. At least, not exactly. Again, it’s complicated. But saying that the pulps were the lesser-quality fiction was relegated, and that the best authors evolved out of them is frankly a myth that ought to be put to rest. Really, it’s the other way around… the market evolved. While certain stories with wider potential could find their way into the higher-paying slicks or other markets, for the most part genre-fiction (science fiction, fantasy, gritty detective, westerns, horror, etc.) was a niche market served almost exclusively by the pulps. There was no other place to go. According to sf-encyclopedia.com, “Many pulp writers sold to [certain] slicks, but few sold them science fiction. The science fiction that they did run tended to be by mainstream writers or those with a literary reputation.”

Meanwhile in the comments, Jon Mollison weighs in on the myth-busting nature of one of A. Merritt’s stomping grounds… and contrasts it to the more cringeworthy aspects of what we’ve had to be told over and over again is a “golden age.”

I don’t accept the received wisdom that the fantasy and sci-fi genres were niche any more than I accept the received wisdom that the writing in the pulps was substandard. The low-cost pulps might not have had the circulation of the slicks, but be careful that you don’t apply a 1950’s understanding to the entire fifty year history of the pulps. In the earliest days, one of the largest fiction magazines, Argosy, included fantasy and sci-fi cheek to jowl with more grounded adventure fiction. I have yet to see a contemporary (read: 1920’s or 1930’s) account describing SF/F’s position as low-rent or kids-stuff.

It’s only when you get to the late 1940’s and early 1950’s that you start to see the idea of SF/F as a ghetto…and I’ve only ever seen that idea was promulgated by the people who claimed to own the map to the literary promised land! Which brings us to your latter question. The Campbellian plan led to disastrous results. Instead of looking wise, mature, and dignified, they looked desperately insecure and were judged accordingly. The literary critics responded to the SF/F leadership’s Stuart Smalley-esque “I’m smart enough, I’m good enough and gosh darn it, people like me,” mantra the same way we react to Stuart Smalley – by thinking, “Only somebody with serious issues needs that kind of affirmation. There must be something seriously broken inside SF/F.”

One little wrinkle – that’s a gross oversimplification. I think Campbell just wanted to sell magazines, and saw what we now call “Hard SF” as a method of branding his title. Unfortunately, he opened a Pandora’s Box that was used as a bludgeon by men operating in bad faith over the next three or four decades, men who wrote our current understanding of the pulps to paper over their own failures.

That’s one more reason to read pulp authors: they just weren’t tainted with this weird desire to be taken seriously. Just as one example, I got ahold of The Man in High Castle hoping to get something edgy, weird, off-beat, and “out there.” What I ended up getting was basically “Flannery O’Connor Lite” written by a guy that… well, that really wanted to graduate to some strain of “real” writing. To be accepted by the “real” writer types of the sort of literary establishment that would have sneered at Tolkien. It really grates!

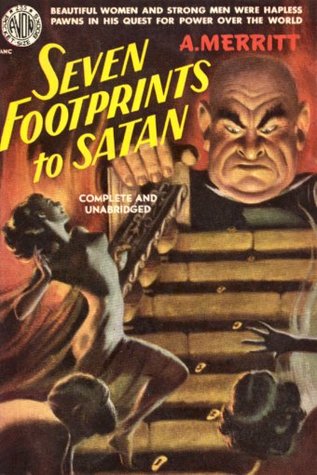

A. Merritt never went through any of that. Even this stigma people were supposed to have for having their real name associated with their pulp writing… it just wasn’t there with him. As editor of The American Weekly, he climbed about has high as a writer could get in the period. He wrote his adventure stories as a sideline… to a generation that saw his work as being merely an exciting form of fiction. The stigma wasn’t there because the dweebs and weirdos responsible for creating it hadn’t taken over the field, yet!

Time and again people assume it’s safe to extrapolate what they think they know about fifties era science fiction backwards into the pulp era. They don’t go read for themselves! Thus, the truth about the pulps remains a well guarded secret… in spite of the fact that it’s never been easier to get the original magazines.

Rampant Coyote has a great blog. He got me interested into the pulps, years before I found out about this site.

-

His Frayed Knights game is pretty good, too. I really need to get back to it and finish it.

-

I’m awaiting the sequel, but it’ll probably take a while.

Frayed Knight is pretty fun.

-

“As editor of The American Weekly, he climbed about has high as a writer could get in the period.”

The Atlantic Weekly had the biggest circulation of any periodical/circular in the US when Merritt worked there. He eventually became editor-in-chief. Merrit was instrumental in starting the art careers of Virgil Finaly and Hannes Bok. The man was making big money besides what he brought in from his bestsellers. He was also kept busy by his day job; one possible reason for his relatively low output.

Merritt simply loved writing weird fiction. It’s the only way to explain why he contributed to fanzines and how he interacted with fans and authors of lesser success at the time.

Here’s an account from Forry Ackerman, who was a total teenage nobody fanboy during that period:

http://swordsofreh.proboards.com/post/8909/thread

I’ve noticed that as well. The people who are the most dismissive of pulps almost never have had any exposure to them.

And the one or two that I’ve met that have actually read, but not enjoyed ERB or REH, well, they are uptight sticks in the mud anyway.

This sort of false received wisdom reminds me of westerns. I once found myself around a bunch of really hardcore western fans, guys who have read and watched hundreds if not thousands of works, and I figured I’d ask them if any could point out to me some of those “white hats vs. black hats” stories we’re told dominated the genre before it grew up in the 50s and beyond. I wasn’t asking cynically – I genuinely was curious because although I enjoy many westerns, I’m nowhere near as up on the genre as I’d like, especially the written form.

These guys…couldn’t name a single story. Sure there were some poorly written stories and some things for kids that you would expect to be simpler, but the western was always a strong and diverse genre. It never needed to grow up or be redeemed or transcended or what have you. But whenever people talk about a classic work, they throw out that line about how “before [insert title], the western was stupid and good guys wore white and bad guys wore black, because it was stupid….”

In the 1920s and 1930s, pulp writers like Erle Stanley Gardner were making 5 cents a word (slightly less than SF pro magazines pay today). That was good money — Lester (Doc Savage) Dent could afford an ocean-going sailboat and Walter (The Shadow) Gibson had a private railroad car to travel in. Of course, they had to maintain a BRUTAL writing pace to make that: half a million words a year or more.

But by the 1950s, pulps were still paying a few pennies a word while the slick magazines were MUCH more lucrative, paying ten cents or better per word. I recall a tossed-off remark in one of Roald Dahl’s essays about how he could support himself by writing a couple of short stories a year. And Mr. Dahl did like to live well. He probably could sell each story two or three times (US/UK/foreign) so a given story might earn him 3000-4000 dollars. That in an era when average wage was $5000 a year.

So there was an incentive for SF and fantasy writers to adopt a more “literary” style if they could make two or three times as much money by doing so.