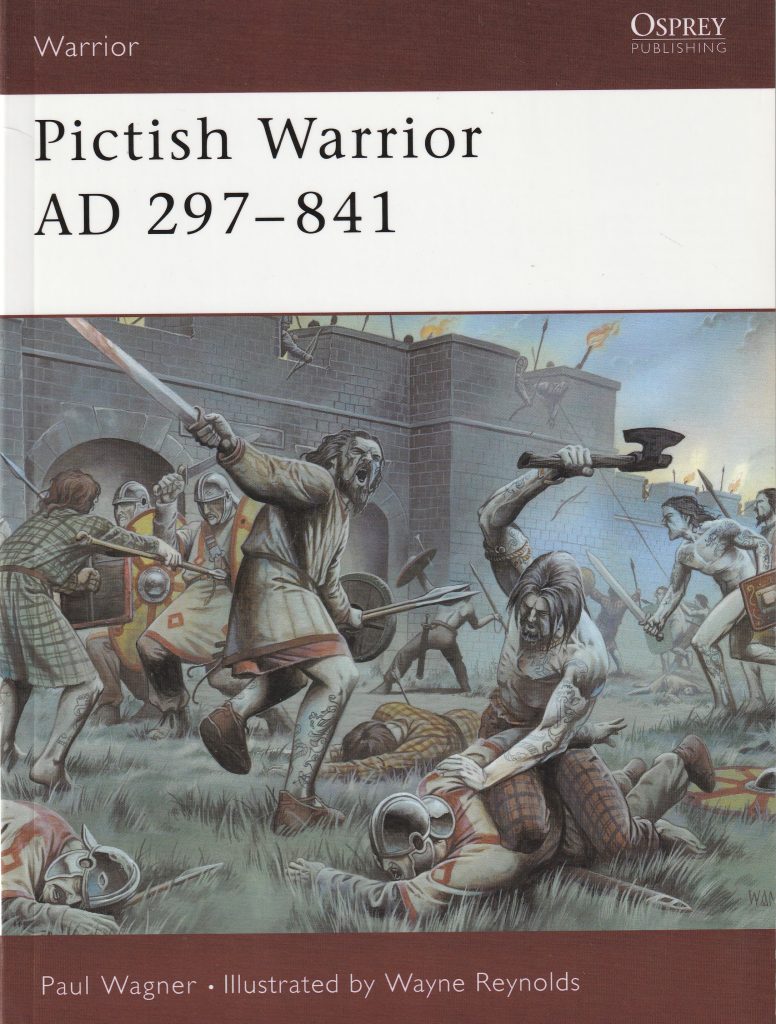

Osprey Publishing’s Pictish Warrior AD 297-841 is number 50 in their Warrior series originally published in 2002. Author is Paul Wagner with illustrations by Wayne Reynolds.

Osprey Publishing’s Pictish Warrior AD 297-841 is number 50 in their Warrior series originally published in 2002. Author is Paul Wagner with illustrations by Wayne Reynolds.

The Picts are an enigmatic people of the British Isles first mentioned in 297 A.D., a regional power until succumbing from hammer blows from the Scots and Vikings. Robert E. Howard enshrined the Pict as the eternal barbarian. He imagined them as short, olive skinned Causcasoids of the Mediterranean physical type. They are present in the time of Atlantis when Kull was king of Valusia. Conan of Cimmeria fought them in the Hyborian Age. Bran Mak Morn leads the Picts against the Romans, Cormac MacArt both fought and allied with in the 5th Century, and Turlogh O’ Brien encounters them in the 11th Century.

Who were the Picts? Peter Berresford Ellis has this to say in Celt and Saxon:

“The so-called Picts have been perceived as a separate people and , as such, they have become the subject of myth upon misconception. Even today, many believe that the Picts were a non-Celtic people. The name ‘Picti’ was first recorded in a Latin poem of AD 297. However, they were not a new element in the tribes of Caledonia but the same Brythonic-speaking Celtic tribes, calling themselves Priteni, and united in a tribal confederations. The place-names in the are unquestionably Celtic, as are the names in their king lists.”

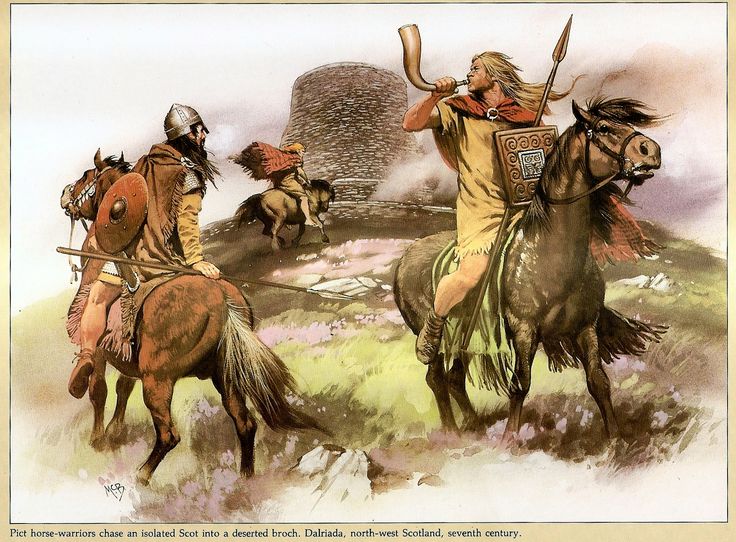

The issue might not be so cut and dry. Wagner discusses two different cultures roughly divided by Loch Ness. To the north was a culture that built the cylindical Brochs while to the south had the more typical Celtic ring-fort. There was an expansion of broch building south after Agricola’s victory at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Wagner makes a good case that Pictish power was originally in the Orkney Islands spread south.

He points out that St. Columba from Ireland could converse with the Britons of Strathclyde but needed interpreters when dealing with Picts. Bede said the Picts came from “Scythia.” Bede said Pictish was a separate language from English, Gaelic, and British.

Wagner builds a case the Picts might have been warriors from elsewhere first established in the Orkneys and took over territory devastated by the Roman Emperor Septimus Severus in 208 A.D. There are Irish legends the Picts were given Irish wives. Maybe they were from “Scythia,” a band of Balts or Sarmatians who found themselves in the British Isles.

The Picts do appear to be better organized than the rest of the Celts. They fought Roman, Scots (Irish Gaels), Britons, Angles, and Vikings. Maybe they were a warrior caste like the later Normans who took Irish wives and “became more Irish than the Irish.” Wagner discusses the warrior band culture of the time. He goes into swords, axes, spears, helmets, armor. He gives some space to the horses used, their appearance, and descendants of both the small and larger horses. The Picts may have used an ancestor of the Scottish Deer Hound as a war dog. He discusses Pictish culture including their pre-Christian religion.

Of course, the end of the Picts is covered as some bad defeats were inflicted by the Gaelic Scots of Dal Riata and the Vikings. The Pictish state collapsed with the destruction of their warrior elite. The culture followed. Maybe the Pictish realm was one ruled by a foreign elite over a Celtic community. W. A. Cummins made the case of a pre-Pictish Gaelic substrate, especially in Galloway in The Age of the Picts.

Much is supposition. Peter Berresford Ellis has written how the Calvinists burned many of the written works during the Scottish Reformation. What we know of the Picts is from Irish, Roman, and English sources.

Angus McBride from Tim Newark’s Celtic Warriors

Please give us your valuable comment