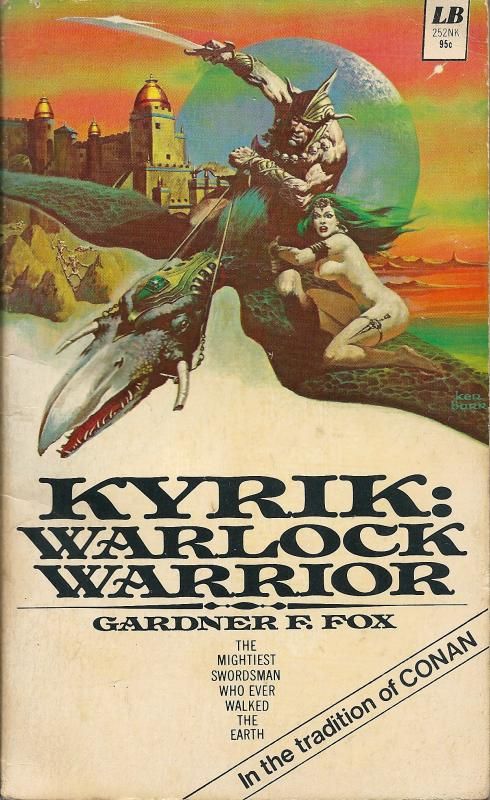

RETROSPECTIVE: Kyrik: Warlock Warrior by Gardener F. Fox

Monday , 23, February 2015 Appendix N Leave a comment Compared to Gardener Fox’s other Conan knockoff,¹ this one is actually pretty good. Instead of a collection of episodic stories, this book serves up a complete short novel. Instead of taking place in the far future on a distant world, this tale is set in a mythical past. Instead of a goof bumbling around with a magic sword that ensures victory at the cost of keeping the protagonist in a permanent state of poverty, this book features a guy that can rise as far as he cares to go. And instead of a single feminine foil to tag along on the hero’s adventures, this book features three: a beguiling sorceress, a saucy gypsy girl, and a lascivious demoness.

Compared to Gardener Fox’s other Conan knockoff,¹ this one is actually pretty good. Instead of a collection of episodic stories, this book serves up a complete short novel. Instead of taking place in the far future on a distant world, this tale is set in a mythical past. Instead of a goof bumbling around with a magic sword that ensures victory at the cost of keeping the protagonist in a permanent state of poverty, this book features a guy that can rise as far as he cares to go. And instead of a single feminine foil to tag along on the hero’s adventures, this book features three: a beguiling sorceress, a saucy gypsy girl, and a lascivious demoness.

Kyrik’s got his hands full playing his romantic interests off each other to be sure, but being a good guy he’s mostly about his business of taking back his kingdom and getting even with the people responsible for putting him away for all those thousands of years. The book’s like something out of a weird parallel universe where cheap supermarket novels were tailored to regular guys’ tastes. It’s kind of strange that it even exists.

No, Fox is no Robert E. Howard. He rips through one scene after another without really developing the suspense. He also tends to get pretty talky as well. It’s almost like he’s used to writing for a comic book where someone else can come along after him and flesh out what he has in mind. I will say this, though: the man knew how to pay off what he sets up. It’s kind of hokey, sure– about like the ending of the original Star Wars movie that came out about the same time– but it’s strangely satisfying. If this had been done a decade or so later, it could have ended up being pointlessly blown up into something three times as long. Worse, it could been written from the start to just sell the next book of a series that’d never actually see completion. Or maybe the last couple of installments would have that “contractually obligated” feel to them as they peter out.

Given my gaming advise from back when I covered Lest Darkness Fall, it was funny to see how Fox made made a point have the hero set up a regency at the end so that he could be free to adventure however he pleased. I’ve also advised game masters to allow their players to run their domains as anachronistically as they wished– and it’s funny to see this odd idea taken to almost ludicrous extremes:

He went with his guard about him out into the city streets. There were people here, staring and worried, and Kyrik went among them to take their hands and speak with them, promising a lessening of their taxes, an easing of their lives. There would be no more torturers; if a man commiteed a crime and deserved to die so that the rest of society would be safe, then it would be clean, swift death.

Through the night he went, into the taverns and the alehouses, and spoke with the common man and his woman, and left them with tears in their eyes. Peace and contentment was come upon all Tantagol, he assured them, there would be a celebration at his expense when men could feast and become drunk and make love, and there would be no curfew, nor any spies to stare upon them and report their words. (page 146-147)

Barbarians… they not only have a preference for consensual sex over rape, they’re also fiscal conservatives that know how to party.

Hard-nosed realists will have a hard time with that, but really… it’s about the only way to make this sort of character at all likable. The author is on the hook to put the spotlight on someone the reader will want to see succeed… and that character needs to still be likable even after he pulls of his caper, too. It may not make any sense to have uncivilized swordsman end up being the second coming of America’s Founding Fathers, but people eat it up anyway. It works.

From a pure fantasy gaming standpoint, one of the more interesting parts of the book is that the sorceress character actually ends up losing her coffer of spell components.² This doesn’t entirely strip her of her abilities: she can still summon up a cloud of “blackness shot with lightnings” if she has enough time to gather “certain herbs” that are relatively common in the wild.³ And she seems to be able to cast a soap bubble themed Sleep spell without any arcane ingredients.⁴ But by the final climatic encounter the loss of that coffer really does prevent her playing a part as some sort of deus ex machina for the hero. Given that novice Dungeon Masters are loath to separate players from the spell books,⁵ it’s pretty useful to see how all of this plays out in the context of a straight up swords and sorcery story. The action here closely mirrors the wild inventiveness of players that are bereft of their tested “I win button” strategies.

While Aryalla’s magic is not too far off from what you’d see in a typical AD&D session, her debut in the pages of this relatively obscure novel nevertheless involves her summoning three demons at once:

A moment she paused, glancing about the room. Then her hand loosened clasps, the garment fell away and she stood proudly nude in the lamp flames. Drawing air into her lungs, she then stepped into the center of the pentagram.

From the casket with the silver clasps she drew powders, rare and tinted with the hues of the rainbow, and of these she made piles, here and there, and touched them with the flames from the lampwick. A blaze of colors lifted like pillars from the pentagram, went upward toward the beamed ceiling hid amid the shadows.

A faint perfume came into the room. She raised her bare arms.

“Demons of the worlds beyond our ken! You who dwell where no man’s eyes may see, where no man’s limbs may go except that it be your will– heed me! Open wide your senses, hear my words!”

Aryalla paused to draw breath.

“Kilthin of the frozen weald of Arathissthia! Rogrod of the red fire-lands of Kule! Abakkan the ancient, bent with the wisdom of ten thousand times ten thousand nether worlds! I appeal, I cry out my needs, I summon you to this plane, this land where I wait your coming.” (page 19-20)

These guys sound like they’d look fantastic in four colors and on a lavish two-page spread. She doesn’t do anything too creepy or horrific with these things, though. For instance, she offers no sacrifices and doesn’t sell her firstborn son to them or anything like that. Other than reversing Kyric’s transformation into a bronze statuette, the purpose of this trio of demons is mainly to provide information. The next creature of the occult which we run into is a different matter, however:

“You did yourself a good turn when you slew Isthinissis. Devadonides counts on him for much help in those necromancies of Jokaline.”

Kyrik remembered what Illis had whispered to his mind in the temple. He asked in surprise, “How can a big snake– or whatever Isthinissis was– help Jokaline the wizard?”

“He wasn’t just a snake. That was only his earthly form. He is a demon god, in his own world. Or so I’ve heard it said. But it was as a reptile that he could work the wonders Jokaline asked of him. His snake body served as some sort of– of gateway through which his demonic powers could pass. Without that body, he isn’t as strong as he was. (pages 114-115)

I can’t say that I’ve ever seen anything quite like that in a game: a wizard that gets a set of spell points, spell slots, and/or special abilities that are tied to having a demonic monster holed up in a temple a few hexes away from his domain capital? That’s just awesome! You get the idea that he has to feed it a regular diet of virgins in order to keep the mana flowing, too. Without this gateway to demonic power, the wizard Jokaline is nowhere near as big of a problem at the end. Not when Kyrik has so many powerful allies working with him to help him successfully navigate the gauntlet of traps that protect the guy. This all leads to the obligatory epic showdown:

Toward the greater pentagram he hurled himself, toward Jokaline. The old man screeched, shouted indistinguishable words. The great prism set into the floor darkened, grew black, shot through with flames.

‘Absothoth comes,’ whispered Illis.

Kyrik was inside the pentagram, had caught the old man in a mighty hand, whirled him upward off his feet, hurled him. Through the air he flung him, right at the great prism. His old body hit the crystal facets of the living gem, collapsed at its base as he slid down those smooth, hard sides….

Kyrik whirled. The prism was melting, flowing into nothingness. And from its deep a dark being was rising upward, amorphous, evil, its fangs showing in a triumphant grin. What served for its eyes– red stars that glittered with demonic fury– glanced down at the gibbering Jokaline who sought to crawl away from the base of the great prism that was its doorway into this world, away from that which he had summoned. Outside the great pentagram Jokaline was prey to that which had served him and obeyed his commands across the many years. Well he knew that hatred Absothoth held for him and so he tried to flee.

“Great Absothoth! Mighty lord of the nether hells! Always I have worshiped you. Always have I given sacrifice in your name. Living men, living women, all have been fed to you– by me!”

The black being laughed, booming laughter that rang in the chamber. “Only by sacrifice could you command me, Jokaline. You gave me helpless humans to further your own ends, to keep me in thrall to you. Now– I find you outside the pentagram!”

Something like a black hand, a clawed paw, darted. It sank into Jokaline, held him motionless under the paws of a cat. (pages 132-134)

This was all being written right about the same time that the Dungeons & Dragons game was gaining the sort of supplements that would grow it into the much larger “Advanced” incarnation of the franchise. Like, everything else in the Appendix N list, it could have had a direct impact that game’s rules… but in the case of demonology, the game just seems to go off on a bewildering tangent. Consider the attributes for demons and devils that were laid down in the iconic 1977 Monster Manual:

- All devils have a range of spell abilities at their disposal: Charm Person, Suggestion, Illusion, lnfravision, Teleportation, Know Alignment, Cause Fear, and Animate Dead. Demons may use Infravision, Darkness, Teleportation, and Gate. Most demons and devils have additional spell abilities beyond this to such an extent, they are essentially high level spellcasters that don’t have to track spells used per day.

- Most demons and devils have the ability to gate in additional demons. The chance of success and a table detailing the summoned types are included with each monster entry. (It is not stated as to whether or not summoned demons can or cannot summon additional creatures when they are summoned.)

- All devils can direct their attacks against two or more opponents if the means are at hand.

- All but the weakest demons and devils have a specified level of magic resistance.

- Most powerful demons and devils have psionic ability and their attack modes and defense modes painstakingly broken down.⁶

The game’s off the wall approach to demons and devils illustrates how even though D&D was inspired by a diverse range of fantasy and science fiction, it rapidly diverged from it to become very much its own distinct thing. Most of this stuff is the result of cobbling things together out of pre-existing game elements rather than a serious attempt to translate their literary antecedents into game form. And AD&D strenuously differentiates between demons and devils. This fetish for taxonomy continues in Monster Manual II where daemons are added into the mix as yet another class of creature. This kind of hairsplitting seems to be a consequence of a syncretistic cosmology being diffused throughout the game. Every conceivable pantheon is incorporated into the “official” AD&D campaign setting by relegating them to their own individualized plane of existence. Devils, for instance, form a rigid Lawful Evil hierarchy– and in an homage to Dante, hell itself is broken up into sort of a nine level dungeon. The overall effect here is reminiscent of DC comics buying up its competitors and then cordoning them off in their own separate parallel universes.

A lot of contributors to the game seemed to perfectly able to overlook the various peccadillos of the Monster Manual format,⁷ but the institution has garnered more than its fair share of critics over the years. For instance, Wayne Rossi over at Semper Initiativus Unam has pointed out that the release of the first Monster Manual not only eliminated the original game’s science fantasy elements, but it also established for demons, dragons, and humanoid monsters a bewildering range of canonical types.⁸ He suggests that it would have been better if they’d replaced color coded dragons and named demon princes with random tables. The funny thing is, Gary Gygax did in fact include such tables in an utterly forgettable appendice of his Dungeon Masters guide.⁹ Unlike John Pickens’s earlier article along these lines,¹⁰ Gygax’s tables take great efforts to create not just the combat statistics, but also a very specific look for the creature, with a range of possible results for the eyes, nose, moth, arms, legs, skin, and even body odor.

Far more interesting is an article by Gregory Rihn from about the same time and whose material was specifically passed over when the Dungeon Masters Guide was later compiled. It suggests using the spell research rules to allow magic-users to discover the name of demonic entities. The name of more powerful creatures are treated as being higher level spells, though you don’t always end up with the exact sort of demon you were aiming for. Once the name is known, a separate ritual for summoning the critter must also be researched. Lesser demons require tributes or sacrifices each time they are called up. The more powerful demons will require a thousand years of service in the afterlife or even permanent forfeiture of the spellcaster’s soul. In addition to gaining access to new spells, information on the names of other demons and the all around fighting ability of the monster, the deals with these creatures can also involve details that spill over into the domain game:

In making a pact with Asmodeus, the archfiend may offer twenty years of service in return for a promise that the operator worship him, build a place of worship consecrated to him, dedicate half of all his treasure to him, raise an army and stamp out good religions in a given area, and perform sundry other little jobs. Plus, of course, the operator must forfeit his soul at the end of the contract.

While this is certainly in line with works ranging from “The Devil and Daniel Webster” to “The Devil Went Down to Georgia”, it’s nevertheless hard to imagine individual players caring too much about the actual souls of their various player characters. That’s why it’s such a delight to read how Lewis Pulsipher hammered out game effects of just this sort of thing:¹²

The demon offers to aid the character on occasion in return for his soul, and the souls of others through sacrifice. The character, when killed, cannot be resurrected by any means other than a Wish. Even if a Wish is used. sooner or later the demon prince will discover that he has been robbed, and will thereupon immediately hunt for and obliterate that character.

In both of these articles, you get far more concrete rules for how to handle demons and devils in the course of play than anything you’ll find in the “official” supplements. But as good as they are, they also omit any mention of the Demons’ amulets and Devils’ talismans, two offbeat items that garner a couple of paragraphs in Gygax’s original Monster Manual entries. Items along these lines actually turn out to be a critical plot element in Gardener Fox’s first Kyrik novel, being an major aspect of how the demons Illis and Absothoth are depicted. While this may not be the sole source for Gygax’s ideas here, it’s certainly interesting to see something along these lines worked out into something that could be developed into an actual gaming scenario.

Demons are formidable creatures with a great deal of mythic significance. It’s hard to see them slapped into the game as sort of an amalgam between extra tough ogres and high level magic-users. There really should be more to them than that, but you just don’t tend to get much help from the game manuals on that sort of thing. This absence of coherent guidance is something that was carried forward into the second edition of the game: the Dungeon Masters Guide for that particular iteration makes no mention of any of this! This was no doubt an intentional omission, done to appease the Puritanical mobs that supposedly made it their mission to clean up pop music, roleplaying games, and River Cty.¹³ This a topic that has a major impact on the game’s depiction of magic, clerics, and the overall cosmology… and it was simply erased from the core books in order to avoid offending people. At the exact moment that a more coherent synthesis was what the game needed most…!

Which brings us to Ron Edwards, who can fairly be characterized as being part of a wider correction in response to TSR’s tendency towards watering down of the game over the years. His take on demons may seem somewhat unconventional, but it too has a precedent in this battered old Appendix N book. While Kyrik the Warlock Warrior can be easily translated into Sorcerer terms, it’s something of a surprise to see that his demon Illis follows the game rules almost to the letter. Being a self-styled Goddess of Lust, she naturally has a desire that is in line with that. She is capable of concealing her human form by transforming herself into a small snake which wraps around the hilt of Kyrik’s sword, but her telltale of eerily whispering warnings and suggestions will give away her occult status. Finally, she doesn’t dole out favors just for the kick of it, but she also has a need that is straight out of the Sorcerer rule book:

He hastened back toward Illis in her worshipping chamber. She was moving about the room, graceful, lissome, and once more Kyrik wondered at her shape and form in those demon lands. She laughed at the sight of him and his bloody sword and ran to him on bare feet.

Her fingertips touched the bloody blade, wiped it clean. As might a child, she put that finger to her mouth, licked off the blood. Her blonde eyebrows rose questioningly.

“Do I shock you, Kyrik darling? Is my thirst for blood so baffling to your human mind?”

His wife shoulders lifted, fell. “There are night creatures who need blood for life. To you it’s a tasty thing. Who am I to condemn your demon ways?” (page 92-93)

Gardner Fox’s short novel, unpretentious though it may be, is loaded with game-inspiring material like that. It’s not just that it shows good half dozen demons in action, either. It also shows several different ways that those monstrous cross-planar entities can be leveraged in the context of typical adventuring situations. The fact that its subject matter was subjected to some sort of purge in the eighties only makes it that much more interesting today. Just the idea that this sort of thing is across the line makes it more fun to check back into it today, but the fact that D&D’s treatment of other planes never quite set well with me is one more reason why the sequel to this is going on my reading list. “Kyrik Fights the Demon World”? Yeah, that’s something I have to see…!

—

¹ That would be Kothar, which we covered back in October.

² See page 105.

³ See page 121.

⁴ See page 128.

⁵ See Dungeon Masters Rulebook (Red Box version) at Technoskald’s Forge for an example of this sort of reticence. (Going by James Ward’s “Notes From a Semi-Successful D&D Player” in The Dragon #13, Dungeon Masters in the bad old days had no such qulams: “a set of extra spell books for the magic user is a must. Those things are too easy to destroy, steal, or lose. I know the cost is extreme, but considering their need for you to simply exist as a magic user, they are a must.”)

⁶ Note that just as Gary Gygax would later regret including the monk class in the core AD&D game, he would also acknowledge a need to remove the unusual psionics system in subsequent editions of the game: “Quite frankly, I’d like to remove the concept from a medieval fantasy roleplaying game system and put it into a game where it belongs something modern or futuristic.” — (Dragon Magazine issue #103, page 8)

⁷ Going by “Demons, Devils and Spirits” in Dragon #42, Tom Moldvay seems perfectly able to operate within the constraints of the AD&D game system.

⁸ See Nuking the Monster Manual over at Semper Initiativus Unam for more on this.

⁹ Gary Gygax’s “Random Generation of Creatures From the Lower Planes by Gary Gygax” first appeared in The Dragon #23.

¹⁰ Jon Pickens’s “D&D Option: Demon Generation” appeared in The Dragon #13.

¹¹ Gregory Rihn’s “Demonology Made Easy; or, How To Deal With Orcus For Fun and Profit” appears The Dragon #20.

¹² Lewis Pulsipher’s “Patron Demons” appeared in Dragon #42.

¹³ While the the actual extent of the influence groups like B.A.D.D. merits further investigation, it’s clear that role-playing game designers behaved as if there was a real threat. Even as late as 1995, TSR bent over backwards to distance themselves from the sort of game depicted in the Tom Hanks TV movie Mazes and Monsters. This is documented in the writers guidelines they published on AOL at the time.

Please give us your valuable comment