Fantasy role-playing games from their outset have included the possibility of epic level play. And though players often passed over these possibilities in their campaigns, nevertheless it was integral to the zeitgeist of the medium. In first edition Tunnels & Trolls, player characters could raise their attributes to god-like proportions as they leveled up. In AD&D, the spell slots of clerics and magic users keep increasing all the way up the level 29 and the default campaign world is littered with artifacts that could rival Tolkien’s One Ring. Deities & Demigods includes rules for the ascension of player characters so that they can join the pantheons of their game settings. And the classic Mentzer boxed set series of the eighties included two installments beyond domain level play: Master and Immortal rules. Even when a campaign was destined to last only for a summer instead of the years of weekly sessions required for this sort of achievement, the potential for this sort of thing remained a core part of the game’s appeal. For most characters, a pit trap in the next hallway could very well be the end of them, nevertheless they still strode across the game world as if they were temporarily embarrassed demi-gods.

Fantasy role-playing games from their outset have included the possibility of epic level play. And though players often passed over these possibilities in their campaigns, nevertheless it was integral to the zeitgeist of the medium. In first edition Tunnels & Trolls, player characters could raise their attributes to god-like proportions as they leveled up. In AD&D, the spell slots of clerics and magic users keep increasing all the way up the level 29 and the default campaign world is littered with artifacts that could rival Tolkien’s One Ring. Deities & Demigods includes rules for the ascension of player characters so that they can join the pantheons of their game settings. And the classic Mentzer boxed set series of the eighties included two installments beyond domain level play: Master and Immortal rules. Even when a campaign was destined to last only for a summer instead of the years of weekly sessions required for this sort of achievement, the potential for this sort of thing remained a core part of the game’s appeal. For most characters, a pit trap in the next hallway could very well be the end of them, nevertheless they still strode across the game world as if they were temporarily embarrassed demi-gods.

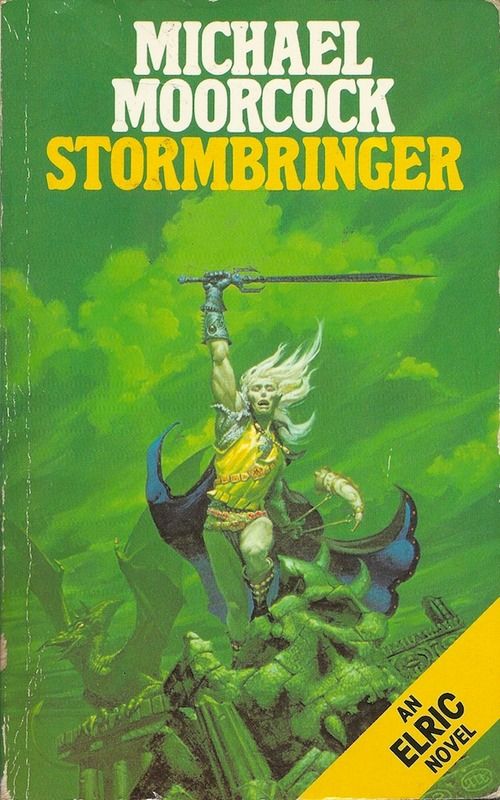

Looking over the literary inspirations for classic D&D, there’s actually not a whole lot there that reflects this sort of thing. While Conan and John Carter follow the classic “adventurer, conqueror, king” sequence to a tee, godhood is beyond the scope of their respective retirement plans. Roger Zelazny’s Chronicles of Amber and Philip José Farmer’s World of Tiers series present god-like protagonists, but neither are consistent with the end games presented in classic editions of D&D. There’s pretty much just one author that is responsible for godlike achievements being the default destiny of those rare player characters that can actually survive years of almost constant gaming: Michael Moorcock. If you want to see the original template for this premise, then there’s really only one book you need to read: Stormbringer.

The surprising thing about this is that, more than anything else in the Appendix N list, the plot of this book is a railroad after the fashion of the worst sort of role-playing game adventure module. In retrospect, this is maybe to be expected– after all, by this installment of the Elric series the hero not only has a sword that can instantly kill any mortal, he also gets hold of a magic horse that eliminates terrain effects altogether and a shield that can protect him from the attacks of even god-like beings. When a character progresses to the point where neither the combat system not the wilderness travel rules can provide any sort of challenge for him, how on earth do you craft a suitable scenario for him?!¹

Moorcock’s solution to this problem will be immediately recognizable to anyone that’s spent much time role-playing. This novel really is a great summary of what not to do as a game master:

- Have the forces of Chaos break into the player character’s castle to kidnap a loved one. Provide just enough clues as to what’s going on that the player has no choice but to go on a wild goose chase. (Note: if your players characters don’t have any friends, love interests, or extended family, this is why!)

- Draw the player into a massive battle where the outcome is pretty much preordained. As the player flees the battlefield, leave only one avenue of escape. Have the enemy forces cover every other direction than the one where the next adventure situation lies.

- Introduce an epic-level NPC that can dole out missions on whatever basis fits the game master’s preparations. With the nature of reality at stake, the player has no choice by to comply. (This sort of format pretty well steamrolls any influence the players might have had on the direction of the campaign. While it does simplify preparation requirements, it comes at the expense of player autonomy.)

- Only rarely give a choice to the players, but make it a very limited set of options that always lead the the next adventure situation regardless of the outcomes. (This is perhaps unavoidable in some strains of computerized adventuring… but with real life role-playing this is generally considered to be a table flipping level of offence.)

If this is the inevitable outline of epic level adventuring, it’s no wondering that most people over the years have spent far more time attempting to figure out how to get the maximum utility from their ten foot poles, iron spikes, and 50′ lengths of rope instead. On the other hand, role-players that are reluctant to push their game systems to the limits really are missing out. It’s really not hard to see why game designers in the seventies were so smitten with Moorcock’s use of extra-planar entities and god-like beings:

Further and further into the ranks he sliced his way, until he saw Lord Xionbarg in his earthly guise of a slender dark-haired woman. Elric knew that the woman’s shape was no indication of Xiombarg’s mighty strength but, without fear, he leapt towards the Duke of Hell and stood before him, looking up at where he sat on his lion-headed, bull-bodied mount.

Xiombarg’s girl’s voice came sweetly to Elric’s ears. ‘Mortal, you have defied many Dukes of Hell and banished others to the Higher Worlds. They call you god-slayer now, so I’ve heard. Can you slay me?’

‘You know that no mortal can slay one of the Lords of the Higher Worlds whether they be of Law or Chaos, Xiombarg– but he can, if equipped with sufficient power, destroy their earthly semblance and send him back to their own plane, never to return!’

‘Can you do this to me?’

‘Let us see!’ Elric flung himself towards the Dark Lord.

Xiombarg was armed with a long-shafted battle-axe that gave off a night-blue radiance. As his steed reared, he swung the axe down at Elric’s unprotected head. The albino flung up his shield and the axe struck it. A kind of metallic shout came from the weapons and huge sparks flew away. Elric moved in close and hacked at one of Xiombarg’s feminine legs. A light moved down from his hips and protected the leg so that Stormbringer was brought to a stop, jarring Elric’s arm. Again the axe struct the shield with the same effect as before. Again Elric tried to pierce Xiombarg’s unholy defense. And all the while he heard the Dark Lord’s laughter, sweetly modulated, yet as horrible as a hag’s.

‘Your mockery of human shape and human beauty begins to fail, my lord!’ cried Elric, standing back for a moment to gather his strength. (page 236-237)

This is as thrilling of a battle sequence as anything in the entirety of the Appendix N list and it’s just getting started. We haven’t even gotten to the part where the Duke of Hell’s mount is dispatched or where his feminine leg is replaced by an insect-like mandible. If you’ve never run anything like this in a tabletop role-playing game, then seriously… what are you waiting for?!² If your concept of fantasy hinges almost entirely on Frodo and Bilbo’s “there and back again” journeys, then this sort of thing is liable to be inconceivable to you.³ But reading this, it realy makes it clear just why gamers back in the seventies took it for granted that game masters would want hard and fast stats for gods and god-like beings.

Ironically, the most epic aspects of classic D&D are in this instance tied directly to what is perceived as being one of the lamest aspects of the game: alignment. As it’s presented in my battered Basic rule book from 1981, Law is little more than a lifestyle choice for law abiding truth telling team players. Chaos, in contrast, is “the belief that life is random, and that chance and luck rule the world.” Its adherents will (just like Elric) keep promises and tell the truth only if it suits them. With chaotic player characters, the needs of the one outweigh the needs to the many– and most importantly they will (just like Elric) leave their friends high and dry at the drop of a hat.

Over the decades, alignment has often ended up being the source of arguments at the tabletop. Few people want any restrictions on their character’s actions, but everyone seems to have a different opinion on how adherents of each perspective would actually behave. Play can grind to a halt as players heckle each other over whether or not their actions are in character or not. In practice, this really is the least “epic” aspect of tabletop role-playing. It’s not heroic fantasy. It’s armchair psychology. And not only does it not make sense, it has a tendency to lead to hard feelings. But even a brief look at Michael Moorcock’s handling of the concept makes it obvious why it could have been taken for granted that something like that belonged in a fantasy game:

As they approached, Elric was soon in no doubt that they were, indeed, those ships.

The Sign of Chaos flashed on their sails, eight amber arrows radiating from a central hub– signifying the boast of Chaos, that it contained all possibilities whereas Law was supposed, in time, to destroy possibility and result in eternal stagnation. The sign of Law was a single arrow pointing upwards, symbolizing direction and control.

Elric knew that in reality, Chaos was the real harbinger of stagnation, for though it changed constantly, it never progressed. But, in his heart, he felt a yearning for this state, for he had many loyalties to the Lords of Chaos in the past and his own folk of Melniboné had worked, since inception, to further the aims of Chaos.

But now Chaos must make war on Chaos; Elric must turn against those he had once been loyal to, using weapons forged by chaotic forces to defeat those self-same forces in this time of change. (pages 154-155)

The key to making alignment relevant then is to tie it to spiritual forces that are active on the prime material plane. Turn them loose to the extent that they end up having sweeping effects on the campaign map, and the players will start to care very quickly about this venerable aspect of the game. This can range from evil sorcerers with dreams of world domination to friendly godlings that have clues about where all the best magic items are. Upset the balance between these competing forces sufficiently and player characters will have to take a stand one way or the other. Faced with the prospects of mankind being twisted into monstrous beings while the earth itself buckles and heaves as the laws of nature lose their coherency and even selfish anti-heroes like Elric can be inspired to do the right thing.

The problem for classic D&D is that Tolkien’s approach to fantasy actually won out over Michael Moorcock’s. In the minds of most gamers and fantasy fans, it seems perfectly natural to keep Eru Ilúvatar and the Valar safely offstage. This trend didn’t stop there, either. Over the decades, “true faith” has ceased having to correspond to anything real; its main requirement is that it be some sort of sincere sort of earnestness about just about anything. In some urban fantasies, a pentagram is as good as a cross against vampires as long as its wielder believes.

People take these sorts of assumptions for granted and then look back at the older games and jump to the conclusion that people must have been just plain weird back then. It’s just not how we do things anymore. But maybe the authors and game designers from back then weren’t so weird after all. Maybe we are. And maybe our hum drum naturalistic approach to fantasy really isn’t as fantastic as it could be.

—

¹ Game blogger Goblin Punch has weighed in on this in Keep Dungeon Threats Threatening. (This link courtesy of Dyvers Best Reads of the Week.)

² Seriously, if you’re consciously saving back this sort of thing, you need to get with it, because as the 1d30 blog can tell you, you don’t have time to build up to something great. (This link also courtesy of Dyvers Best Reads of the Week.)

³ Nerd-O-Mancer of Dork phrases the conventional wisdom on this point like this: “I like that they do not include stats for their gods. Gods are omnipotent beings and shouldn’t be degraded to yet another (if high leveled) monster for the characters to battle.” On the other hand, as Blood of Prokopius points out, if your conception of the gods is derived from pagan sources, this actually is a theologically correct way to deal with them: “These gods are quantifiable because they are part of creation. Ancient creation stories repeat over and over again how all the various bits and pieces of the world are made from some part of the gods themselves. Creation always happens from some kind of pre-existant matter — everything is quantifiable.”

Enjoyed the review, I agree with all your points.

I think it’s a shame that the “stats for gods” lost out in the cultural zeitgeist for D&D. I believe that the reason was that Gods Demi Gods and Heroes gave monster-like stats for *historical* gods like Odin or Zeus (and Monster Manual continued this with a mix of real-life devils amid the made up ones)- and “you just killed Odin!!!” rubbed people the wrong way as the worst sort of power gaming.

Had it instead concentrated on fictional deities you might not have seen the push-back against this that occurred in the mid 80s, and we may have seen more of a nuanced approached, with gradual escalation up to god war levels as a typical part of high-level play instead of being considered an aberration.

I have good memories of reading

Stormbringer for the first time, back in high school, in about my 2nd year of playing RPGs. It was certainly inspirational.

Back then, everyone in our age 14-16 year old high school gaming group were also into science fiction and fantasy and we would trade novels back and forth (usually at the start of gaming sessions). Moorcock was pretty popular, but also Vance, Saberhagen, Zelazny, etc. And we would incorporate elements from this stuff into our next gaming sessions, so that sometimes players would look at what what book I was reading to see if it gave clues as to what they might meet on the next planet or dungeon… though the rule was to always file off enough serial numbers, borrow ideas and concepts, but not rip off characters outright.

I kind of miss that “shared culture” of the fantastic from that era (c. 1979-1981) where we were less “gaming fans” and more “fans of science fiction and fantasy novels who expressed that love through gaming.”

-

This takes me back. Good times.

The whole “godhood” thing removes a lot of the interesting existential drama and pathos of heroic literature. If Gilgamesh hadn’t lost the magic-plant-of-immortality on his way back to Ur, I think literature would’ve been Ruined ForeverTM.

On the other hand, if you subscribe to the cyclical view of Ragnarok in the Norse cosmology, godhood was no protection against a young adult with the properly proscribed grave-goods at his disposal.

Always leave them wanting more.

Once certain challenges have become routine and boring, they are no longer challenges. Always have a greater treasure, bigger challenge and more foursome foes ahead. Heroes overcome challenges, and so bigger challenges make bigger heroes.

Another reason for the move to epic play can be necessity. Perhaps the elder gods are stirring once more, or a rival force is attempting to aquire the Doom Brooms of Vadoon, or whatever. The point there is if they players don;t level up, gear up and stop the bad guys, things are going to get very very bad.

Don;t make the last a bluff, either. If the bad guys are getting the Nifty Things and releasing bound demons, the dead, gods, or demonic dead gods, detail how the world is going to hell to the characters, and make them work a little harder to fix it.

When they finally hit epic, and have the big showdown, it’ll all be worth it.

it seems perfectly natural to keep Eru Ilúvatar and the Valar safely offstage

Well, this is where I think meta and reality butt heads.

In reality we have the real question of “why doesn’t God act” which even atheists acknowledge, and no way of answering it to anyone’s satisfaction (the best we can do is guess).

Ah but when you introduce god into a story, the balance has changed. We CAN ask that god why he/she doesn’t act, because they are the author (or in this case, DM) sitting across the table from us. “Because it makes for a boring story” I think ends up rubbing us the wrong way because then it kind of implies that the real God’s more interested in plot and drama than us (He ends up coming off as borderline evil).

Think of the D&D episode of the IT crowd, where Moss uses the game to help Roy work out a personal issue. While fine once in awhile (even heartwarming and funny in this case), letting reality constantly intrude on the game ends up kind of spoiling it. Thus in books and games, we prefer as thick a veil between god and the characters as possible, less we end up having to face and work out our own issues with Him.

At least, that’s my guess as to why Tolkien won over Morcock in the end.

Moorcock was the Philip Pullman of his day. That’s why he’s not remembered as fondly. When you set yourself crossways to the way of the universe you will not resonate with as many people.

His stories live on but an order of magnitude less popularity than Tolkien. If you ever get a Moorcock story made into a blockbuster it will be because of the Tolkien revival.

I’m sensing some animosity towards the Alignment system. It was vital to the books (moral direction) except those of Moorcock who explicitly eschewed that or Lovecraft who assumed an uncaring unjust world.

Don’t get me wrong. Gaming could have started without an alignment system of some kind but not until the culture was ready which wasn’t for a number of years. Now you get explicitly evil games that assume you want to conquer the world so you can enslave folks and make them worship you.

That was possible forty years ago but only because there was the opposite available as the baseline assumptions.