RETROSPECTIVE: The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian by Robert E. Howard

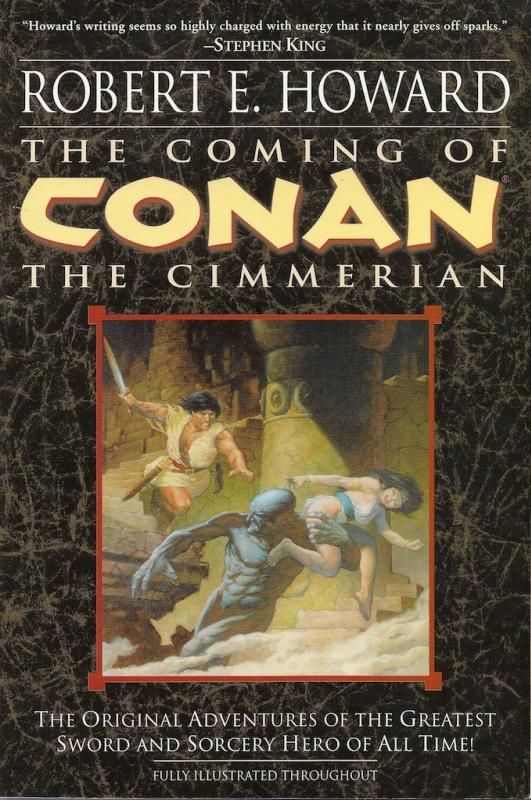

Monday , 22, September 2014 Appendix N 17 Comments When most people think of Conan they tend to think of a wild, black-haired man running around with very little in the way of clothing or armor. Just as Sherlock Holmes is now indelibly linked to his iconic deerstalker, so to is the original fantasy swordsman now wedded in our collective imaginations to Arnold’s Schwarzenegger’s atrocious accent. In spite of this muddying of the waters, the iconic helmet and cloak of the character should still be immediately recognizable even to the more casual fantasy fan:

When most people think of Conan they tend to think of a wild, black-haired man running around with very little in the way of clothing or armor. Just as Sherlock Holmes is now indelibly linked to his iconic deerstalker, so to is the original fantasy swordsman now wedded in our collective imaginations to Arnold’s Schwarzenegger’s atrocious accent. In spite of this muddying of the waters, the iconic helmet and cloak of the character should still be immediately recognizable even to the more casual fantasy fan:

He saw a tall powerfully built figure in a black scale-mail hauberk, burnished greaves and a blue-steel helmet from which jutted bull’s horns highly polished. From the mailed shoulders fell the scarlet cloak, blowing in the sea-wind. A broad shagreen belt with a golden buckle held the scabbard of the broadsword he wore. Under the horned helmet a square-cut black mane contrasted with smoldering blue eyes. (page 122)

But even that is just a snapshot of a single phase of the character’s career. Conan did just about everything and he was rarely “just” a barbarian. He was a mercenary, an adventurer, a thief, and a pirate. He led armies into battle and tribesmen on raids, he captained ships and even became a king:

When King Numedides lay dead at my feet and I tore the crown from his gory head and set it on my own, I had reached the ultimate border of my dreams. I had prepared myself to take the crown, not to hold it. In the old free days all I wanted was a sharp sword and a straight path to my enemies. Now no paths are straight and my sword is useless…. When I led her armies to victory as a mercenary, Aquilonia overlooked the fact that I was a foreigner, but now she can not forgive me. (page 11)

Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories are marked not just by the breadth and height of the hero’s adventures, but range even beyond the boundaries of what we now call swords and sorcery. Many of the early Conan tales would be more rightly termed as being “swords and Lovecraftian horror” or even “swords and evolution.” The backdrop of Conan’s world is thus starkly nihilistic. Conan’s god Crom is a gloomy and savage entity that hates weaklings. His only redeeming quality is the fact that he gives men courage and the will and might to kill their enemies. But in spite of Conan’s straightforward brutality and simplicity¹, he shows more than few traditional virtues. For starters, he is intensely loyal regardless of the consequences:

“Well, last night in a tavern, a captain in the king’s guard offered violence to the sweetheart of a young soldier, who naturally ran him through. But it seems there is some cursed law against killing guardsmen, and the boy and his girl fled away. It was bruited about that I was seen with them, and so today I was haled into court, and a judge asked me where the lad had gone. I replied that since he was a friend of mine, I could not betray him. Then the court waxed wroth, and the judge talked a great deal about my duty to the state, and society, and other things I did not understand, and bade me tell where my friend had flown. By this time I was becoming wrathful myself, for I had explained my position.

“But I choked my ire and held my peace, and the judge squalled that I had shown contempt for the court, and that I should be hurled into a dungeon until I betrayed my friend. So then, seeing they were all mad, I drew my sword and cleft the judge’s skull; then I cut my way out of the court….” (page 123)

Conan’s faithfulness does not change regardless of how high he climbs in stature or authority. He can’t be bought even to save his own life²:

His captors had no reason to spare him. He had been placed in these pits for a definite doom. He cursed himself for his refusal of their offer, even while his stubborn manhood revolted at the thought, and he knew that were he taken forth and given another chance, his reply would be the same. He would not sell his subjects to the butcher. And yet it had been with no thought of any one’s gain but his own that he had seized the kingdom originally. Thus subtly does the instinct of sovereign responsibility enter even a red-handed plunderer sometimes. (page 94)

Even when no one could know of his actions he does the right thing. He reciprocates and fulfills his end of a bargain³ when just about anyone else in the same situation would be willing to walk away. Technicalities or ambiguities are not reason enough for him back out of a deal:

It occurred to him that since he had escaped through his own actions, he owed nothing to Murilo; yet it had been the young nobleman who had removed his chains and had the food sent to him, without either of which his escape would have been impossible. Conan decided that he was indebted to Murilo, and, since he was a man who discharged his obligations eventually, he determined to carry out his promise to the young aristocrat. (page 284)

And though on an individual level he cares for little else than killing and drinking, when he is responsible for a state his reign is marked by a striking combination of fiscal restraint and concern for the weak:

“I found Aquilonia in the grip of a pig like you — one who traced his genealogy for a thousand years. The land was torn with the wars of the barons, and the people cried out under oppression and taxation. Today no Aquilonian noble dares maltreat the humblest of my subjects, and the taxes of the people are lighter than anywhere else in the world.

“What of you? Your brother, Amalrus, holds the eastern half of your kingdom and defies you. And you, Strabonus, your soldiers are even now besieging castles of a dozen or more rebellious barons. The people of both your kingdoms are crushed into the earth by tyrannous taxes and levies. And you would loot mine — ha! Free my hands and I’ll varnish this floor with your brains!” (page 91)

Time and again, Conan shows that he has nothing but contempt for the partiality⁴ that is endemic to more civilized places:

“If what he says is true, my lord,” said the Inquisitor, “it clears him of the murder, and we can easily hush up the matter of attempted theft. He is due ten years at hard labor for house-breaking, but if you say the word, we’ll arrange for him to escape and none but us will ever know anything about it. I understand — you wouldn’t be the first nobleman who had to resort to such things to pay gambling debts and the like. You can rely on our discretion.” (page 56)

And in spite of his humble simplicity and the distant nature of his god, Conan takes a very dim view of both the fatalism and human sacrifice endemic in more “advanced” cultures:

“When I was a child in Stygia the people lived under the shadow of the priests. None ever knew when he or she would be seized and dragged to the alter. What difference whether the priests give a victim to the gods, or the god comes for his own victim?”

“Such is not the custom of my people,” Conan growled, “nor of Natala’s either. The Hyborians do not sacrifice humans to their god, Mitra, and as for my people — by Crom, I’d like to see a priest try to drag a Cimmerian to the alter! There’d be blood spilt, but not as the priest intended.” (page 231)

The people of Conan’s Cimmeria appear to be little more than rough living rednecks that are adept at climbing, but they hold fast to an admirable degree of decency, a code of honor that enshrines a sense of human dignity even as they cut down their foes with the sword. For instance, Conan reacts with disdain towards the Hykranian practice of selling their children. In contrast, the nation of Stygia stands as a manifestation of pure, unmitigated evil:

From where the thief stood he could see the ruins of the great hall wherein chained captives had knelt by the hundreds during festivals to have their heads hacked off by the priest-king in honor of Set, the Serpent-god of Stygia. Somewhere near by there had been a pit, dark and awful, wherein screaming victims were fed to a nameless amorphic monstrosity which came up out of a deeper, more hellish cavern. Legend made Thugra Khotan more than human; his worship yet lingered in a mongrel degraded cult, whose votaries stamped his likeness on coins to pay the way of their dead over the great river of darkness of which Styx was but the material shadow. (page 155)

To them, women are merely bait to be used to bring men to their destruction⁵:

Ships did no put unasked into this port, where dusky sorcerers wove awful spells in the murk of sacrificial smoke mounting eternally from bloodstained altars where naked women screamed, and where Set, the Old Serpent, archdemon of the Hyborians but god of the Stygians, was said to writhe his shining coils among his worshipers.

Master Tito gave that dreamy glass-floored bay a wide berth, even when a serpent-prowed gondola shot from behind a castellated point of land, and naked dusky women, with great red blossoms in their hair, stood and called to his sailors, and posed and postured brazenly.

Conan’s behavior, in contrast, borders almost on chivalry. Sure, if a wench betrays him, he’s liable to throw her over his shoulder unceremoniously dump her into a cesspool. And even under less than dire circumstances, he suffers no shortage of attention from women. Yet he never takes undueadvantage of the women that end up dependent upon him. Whatever sense of morality it is that pushes him to extraordinary levels of honesty in business deals and offices of state are also is at work in his dealings with women:

“It was a foul bargain I made. I do not regret that black dog Bajujh, but you are no wench to be bought and sold. The ways of men vary in different lands, but a man need not be a swine, wherever he is. After I thought awhile, I saw that to hold you to your bargain would be the same as if I had forced you.” (page 316)

Indeed, the “barbarism” of Conan stands out in stark contrast to the norms of more “civilized” peoples⁶:

She had never encountered any civilized man who treated her with kindness unless there were an ulterior motive behind his actions. Conan had shielded her, protected her, and — so far — demanded nothing in return. (page 206)

His romances and dalliances are born from a simmering, mutual passion. Yet with Belit, this burning desire culminates into something profoundly transcendent⁷:

“There is life beyond death, I know, and I know this, too, Conan of Cimmeria” — she rose lithely to her knees and caught him in a pantherish embrace — “my love is stronger than any death! I have lain in your arms, panting with the violence of our love; you have held and crushed and conquered me, drawing my soul to your lips with the fierceness of your bruising kisses. My heart is welded to your heart, my soul is part of your soul! Were I still in death and you fighting for life, I would come back from the abyss to aid you — aye, whether my spirit floated with the purple sails on the crystal sea of paradise, or writhed in the molten flames of hell! I am yours, and all the gods and all their eternities shall not sever us.” (pages 133-134)

While Conan’s fierce loyalty to the women that come under his care often gets him into trouble, his good deeds can also rebound to his favor. He is not following some simplistic script where he always gets to be the guy riding to some damsel’s rescue. Belit called all the shots on her pirate ship, for example. In another instance, he takes charge of a nation’s military forces at the behest of its princess. At other times the key to Conan’s deliverance from hopeless situations rests upon the fair damsel type taking on terrifying risks to reciprocate his freely bestowed kindness. But Conan simply doesn’t do the right thing for what he might get out of it. That never seems to enter his mind. He is so unwavering in his principles, he never bothers to count the cost when faced with any sort of moral dilemma. Death has not the slightest hold on him and not the slightest bearing on his decisions⁸:

Life was a continual battle, or series of battles; since his birth Death had been a constant companion. It stalked horrifically at his side; stood at his shoulder beside the gaming-tables; its bony fingers rattled the wine-cups. It loomed above him, a hooded and monstrous shadow, where he lay down to sleep. He minded its presence no more than a king minds the presence of his cup-bearer. Some day its bony grasp would close; that was all. It was enough that he lived through the present. (page 170)

Indeed, his resolve seems to only increase in the face of mounting odds. Certain death is met with an indomitable insistence on going down fighting.

Conan is a profoundly heroic character. In these early stories, we never quite get a complete picture of his origins. He seems to spring out of nowhere as if he were an instrument of divine retribution, an inevitable nemesis burning a wake of wrath and justice through the “perverse secrets of rotting civilizations.” His world is fully realized, and the tales about him are diverse, but the common thread running through them all is the simple and direct manner in which he embodies courage and loyalty. The alacrity with which he slays and the gusto with which he drinks is matched only by his honesty. Ultimately, it is not his brutality that sets him up as a contrast to the civilized, but rather his integrity.

—

¹ And said, Verily I say unto you, Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 18:3)

² Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends. (John 15:13)

³ Render therefore to all their dues: tribute to whom tribute is due; custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honour to whom honour. Owe no man any thing, but to love one another: for he that loveth another hath fulfilled the law. (Romans 13:7-8)

⁴ If ye fulfil the royal law according to the scripture, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself, ye do well. But if ye have respect to persons, ye commit sin, and are convinced of the law as transgressors. (James 2:8-9)

⁵ For the lips of a strange woman drop as an honeycomb, and her mouth is smoother than oil, but her end is bitter as wormwood, sharp as a two-edged sword. (Proverbs 5:3-4)

⁶ Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me. (Matthew 25:40)

⁷ Wherefore they are no more twain, but one flesh. What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder. (Matthew 19:6)

⁸ Fear not them which kill the body, but are not able to kill the soul: but rather fear him which is able to destroy both soul and body in hell. (Matthew 10:28)

Ultimately, it is not his brutality that sets him up as a contrast to the civilized, but rather his integrity.

Also, his humor. The guy is really full of mirth and wit considering the unjust brutality that surrounds him and the decidedly just brutality that drives him.

-

Let’s see… combines humor, drunkenness, brutality, and a steadfast willingness to sacrifice everything for principle even in a lost cause. Sounds like a run of the mill Scotch-Irish to me!

I read a brief blurb by REH where he talked about his character. My memory is sketchy, but it was something like, he wanted a character that didn’t have to be clever, instead when faced with a tough problem, the character could just hack his way out of it.

In the earlier stories, Conan did, but as the stories unfolded, you could see just how intelligent the character really was.

I wish I could remember where I read it.

-

Howard is the American Tolkien. Both authors wrote of the simple being exalted above the wise and the pure in heart triumphing over corruption. Hobbits and Cimmerians are both quintessentially rural peoples.

-

Yup. I wrote a novel about a rural factory worker who is unemployed but refuses to travel beyond his roots, because those roots need a defender, and he’s the only one who shows up. He is inspired by his childhood obsession with the character of Conan to go into the catacombs and attempt the impossible.

Zero odds, no shields of urban society, a sensibility that blends doom and good humor. That’s Conan.

-

…we never quite get a complete picture of his origins.

This is the primary rule of Conan that the movies violate to their own detriment. The ’81 movie actually presented an origin in an interesting way, but it was still to the detriment of the character from the books. The “new” Conan movie committed suicide right off the bat with not only a Conan-robbing origin story, but a lame one.

Conan stories always start in the middle of things. That’s why the movies aren’t Conan stories.

-

Now that I’ve read the original stories, I have to agree.

Given how well Heath Ledger’s Joker came off, I really wish that Conan could have gotten similar treatment.

-

Love this article Jeffro.

Man, the new Conan movie sucked. Too bad, because I liked Jason Mamoa as Khal Drogo on Game of Thrones.

A new Conan movie is being written now — The Legend Of Conan — and it’s set to star Schwarzenegger in the aging King Conan mold, as he goes out on one last adventure.

-

Beautiful retrospective. No wonder Tolkien had a good opinion on Conan stories.

-

I missed that he had said anything about them. Was it in one of his private letters? Ah, here it is, de Camp’s book Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers:

“We sat in the garage for a couple of hours, smoking pipes, drinking beer, and talking about a variety of things. Practically anything in English literature, from Beowulf down, Tolkien had read and could talk intelligently about. He indicated that he ‘rather liked’ Howard’s Conan stories.”

Though I haven’t read much Conan, he’s always struck me as based more on the ancient pre-christian heroic paradigm rather than the medieval chivalric, the latter of which is much more prominent in modern fantasy. He’s no Knight of the Rose, but a Samson.

-

Though his rags-to-riches rise from obscurity parallels biblical personages like Daniel and David, the actual tone of his characterization strikes me as having more in common with what I’ve read in Herodotus. But yes… while he has a bizarre “gentleman” streak that seems to come out of nowhere, his actions do not smack of chivalry.

-

I always thought of him as a Samson type: the last good Judge in a world gone mad. The fact that he favored no weapon in particular made it seem like he could wield the jawbone of a mule as easily as an Aquilonian broadsword.

-

Good post. I would like to add that even the Stygian worship of Set does not ultimate come out purely as an evil thing. Some of the other stories in other volumes give some glimpses into this.

“His only redeeming quality is the fact that he gives men courage and the will and might to kill their enemies.”

It’s important to note that Crom does that only once – at birth. He doesn’t do it on demand. Conan (in the words of Roy Thomas) swears in Crom’s name, but does not pray to him because, “why pray to a god which does not listen?”