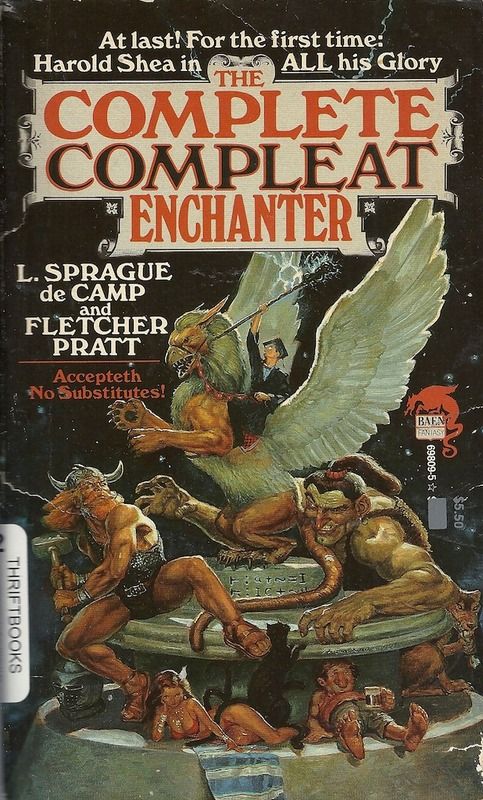

RETROSPECTIVE: The Complete Compleat Enchanter by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt

Monday , 5, October 2015 Appendix N 6 Comments There is an odd passage in the book of Hebrews where the author rattles off a list of all the things he’s not going to talk about.¹ The subjects he takes for granted as being too straightforward and elementary to spend much time on happen to include things that have been hotly debated for centuries. (It’s funny, really.) There’s a similar passage in the first edition of the Tunnels & Trolls game that strikes almost exactly the same cadence:

There is an odd passage in the book of Hebrews where the author rattles off a list of all the things he’s not going to talk about.¹ The subjects he takes for granted as being too straightforward and elementary to spend much time on happen to include things that have been hotly debated for centuries. (It’s funny, really.) There’s a similar passage in the first edition of the Tunnels & Trolls game that strikes almost exactly the same cadence:

There are recognized laws of magic that we have mostly ignored in dreaming up these spells– the Law of Contagion, the Law of Similarity, the principles of necromancy and control of spirits, preferring instead to base most of these spells on inherent abilities of the magic-user a la Andre Norton.

Notice that this is basically an apology. The designer is convinced that his magic system will not function the way people expect. There are laws of magic that he presumes everyone is familiar with and that are foundational to the the topic. And while he can’t take the time to spell all of this out in such a small booklet, he feels compelled to acknowledge this before moving on to the nuts and bolts of his spell system.

Unlike in the case of the epistle to the Hebrews, we do have enough documentary evidence that we can easily unpack every turn of the phrase here. Most people reading fantasy or playing fantasy games today are just not going to be that concerned about the Laws of Contagion and Similarity, but the fact is… it was perfectly reasonable to assume that people in the mid seventies would. The guys that had defined magic for that generation as much or more more than J. K. Rowling has for us today were of course de Camp and Pratt. And they did it with their Harold Shea stories, a mainstay of UNKNOWN magazine.

It’s hard to underestimate just how influential this series of books was in gaming. Ever wonder why it could make sense for a Green Dragon to breath chlorine gas instead of fire? And why giants would necessarily come in three main varieties: hill giants, frost giants, and fire giants? Those mainstay D&D tropes go back to The Roaring Trumpet. Ever wonder why Gygax used the ponderous term “somatic” to denote the hand motions a magic-use needed to use in order to cast a spell? Again, it’s due to de Camp and Pratt:

Half an hour later: “… the elementary principles of similarity and contagion,” he was saying, “we shall proceed to the more practical applications of magic. First, the composition of spells. The normal spell consists of two components, which may be termed the verbal and the somatic. In the verbal section the consideration is whether the spell is to be based upon the command of the materials at hand, or upon the invocation of a higher authority.” (page 271)

Some might argue that this is merely coincidence. It is possible that there was some other inspiration which was shared by both de Camp, Pratt, Gygax, and St. Andre. On the other hand, de Camp and Pratt are not only mentioned in the “Forward” (sic) to Original Dungeons & Dragons, but they are also singled out by Gygax as being among “the most immediate influences” of AD&D. If that isn’t convincing, then note as well that there are very few fans of classic D&D that will not immediately recognize this place:

The door banged shut behind them. They were in a dark vestibule, like that in Sverre’s house but larger and foul with the odor of unwashed giant. A huge arm pushed the leather curtain aside, revealing through the triangular opening a view of roaring yellow flame and thronging, shouting giants….

Within, the place was a disorderly parody of Sverre’s. Of the same general form, with the same benches, its tables were all uneven, filthy, and littered with fragments of food. The fire in the center hung a pall of smoke under the rafters. The dirty straw on the floor was thick about the ankles.

The benches and the passageway behind them were filled with giants, drinking, eating, shouting at the tops of their voices. Before him a group of six, with iron-gray topknots and patchy beards like Skrymir’s, were wrangling. One drew back his arm in anger. His elbow struck a mug of mead borne by a harassed-looking man who was evidently a thrall. The mead splashed onto another giant, who instantly snatched up a bowl of stew from the table and slammed it on the man’s head.

Down when the man with a squeal. Skrymir calmly kicked him from the path of his guests. The six giants burst into bubbling laughter, rolling in their seats and clapping each other on the back, their argument forgotten. (pages 62-63)

This is, of course the Great Hall from Gygax’s “Steading of the Hill Giant”, which is tends to end up being the site of an utterly titanic battle for players undertaking the most iconic module series for the AD&D game. And while it may be a coincidence that one of the giants in that game supplement is indeed pictured as having a top knot, there is another homage in “Hall of the Fire Giant King” here. Both de Camp and Pratt’s story and the adventure module place trolls as guards in the fire giants’ dungeon. I think it’s safe to say that Gary Gygax really, really loved these stories.

How far was Gygax willing to take this sort of thing? Further than a lot of people would think. Most people, for instance, tend to think that the guy was simply being eccentric when they discover that the original name for the “fighter” class was “fighting-men”. The reality is that it’s easier to list the Appendix N books that don’t use that term than it is to pick out the ones that do. And that’s far from the only example of particular turns of phrases being lifted from the designer’s favorite books. As I’ve pointed out previously, the thief in AD&D has a “hide in shadows” skill and an uncannily good ability to climb walls because of the way the thief character is depicted in Roger Zelazny’s Jack of Shadows. By the time I’m flipping through my well worn Moldvay Basic D&D booklet and note that White Apes from Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars are shortly followed up with the green slime monster from Sterling Lanier’s Hiero’s Journey, I begin to assume that anything in the Appendix N books that wasn’t nailed by aggressive legal protections was more than likely bolted onto the game at some point.

And that’s why it gives me pause when I come across passages like this:

“Very fine girl, provided she doesn’t put an arrow through you and cut your ears off for trophies. I confess my taste runs to a somewhat more sedentary type of female. I doubt whether I can stand much more excitement of this sort.”

Shea said: “I know how you feel. Traveling through Faerie is just one damned encounter after another.” His two narrow escapes in one day had left Shea feeling like a damp washcloth.”

Chalmers mused: “It is logical that it should be so. The Faerie Queen indicates that this is a world wherein an endless and largely planless concatenation of encounters are a part of the normal pattern of events…. (page 173)

I’m not the only person that’s run entire game sessions off of little more than a few wilderness encounter charts. Is it possible that such a significant chunk of the original fantasy role-playing game could have been directly inspired by a passage like this? Well… given that the nuances of a Gygaxian style Megadungeon level are plainly laid out on in Margaret St. Claire’s Sign of the Labrys, why not?! (But do note that there are wilderness encounters in Avalon Hill’s Outdoor Survival game, so de Camp and Pratt are not the only potential source for this particular element.)

The point here is that literature was a primary inspiration to tabletop game designers in the seventies in a way that’s very difficult for a lot of people to comprehend these days. When Marc Miller sat down to adapt the the original three D&D booklets into a similarly organized science fiction game, he didn’t think to channel the old Star Trek television series or the Planet of the Apes movie franchise. No, his inspiration came from books by H. Beam Piper and E. C. Tubb. When Steve Jackson sat down to design Metagaming Concepts’ flagship MicroGame Ogre, he had Keith Laumer’s “Bolo” stories and Colin Kapp’s “Gottlos” at the forefront of his mind.

It isn’t like this anymore. And no, it’s not that you can’t find old school games that have healthy reading lists attached to them. (There’s a couple by Alexander Macris and Ron Edwards that I can recommend right off. GURPS Time Travel is loaded with recommendations of iconic works from the Appendix N authors as well, for instance.) But really, for the most part it’s not short stories and novellas and 180 page throwaway paperbacks that dominate the collective consciousness of gamerdom. Most people get their notions of science fiction and fantasy from a handful of top tier properties. When you game master a role-playing game at a convention for a group of strangers, your common frame of reference is not the written word, but a collection of blockbuster movies. And when game designers begin a new project, it’s natural for them think to in terms of pre-existing games, rather than the work of an incredibly diverse set of authors.

The seventies were not like that. When you look at the most enduring game design work of the period, you’re looking at the product of a culture that has ceased to exist. And the generation gap that has emerged due this is exacerbated by the fact that so many of the authors have become unaccountably obscure in a surprisingly short period of time since then. This makes it doubly hard to comprehend some of the old games: not only is their cultural context now largely unimaginable, but the designs in some cases assumed that game masters would have wealth of diverse literature backing up their own creativity.

Some people try to dismiss this as being a topic that’s worth looking into. “Eh,” they say, “times change; this sort of thing is inevitable, really.” Other people diminish the study of the Appendix N by claiming that the books that inspired the Appendix N authors would be far more edifying. But here’s the thing that these sorts of people don’t understand: the “Appendix N” of Appendix N is embedded in Appendix N!

If you want to reach back into the truly foundational stories of Western fantasy, look no further than de Camp and Pratt’s Harold Shea series, which takes a psychologist from the twentieth century and thrusts him into adventures in fantasy worlds ranging from Scandinavian myth, to Spencer’s Fairie Queen, Orlando Furioso, and on to the Kavela and Irish myth. These guys were far from the only Appendix N authors to do something along these lines; even Michael Moorcock invokes Roland in his Elric stories.

But more than betraying a fluency in “real” literature, the Appendix N authors were themselves highly influential to each other. The now virtually unknown A. Merritt occupied the same spinner racks as seventies icon Roger Zelazny. He was a primary inspiration that lead Jack Williamson to launch a nine decade long career writing science fiction. When H. P. Lovecraft wrote his signature story “Call of Cthulu”, he was pretty well writing A. Merritt fan fiction. And on the weird fiction side of things, Lord Dunsany was a major influence on Lovecraft, though we might not even know Lovecraft’s name were it not for the efforts of August Derleth. Indeed, much of what we call “Lovecraftian” today is in fact Derlethian. Finally, Edgar Rice Burroughs inspired not just other authors on the Appendix N list, but countless numbers of scientists and technologists as well.

These authors really were present in the seventies in a way that’s hard to imagine anymore. When John Eric Holmes, the editor of the first iteration of Basic D&D, wrote a series of novels, he didn’t think anything of using Burroughs’ Pellucidar books as the starting point. (That cost him, too. He never got permission to publish his third novel in that series!) The original book series debuted in 1914 and were dated in every way imaginable– to the point of positing a sun inside of a hollow Earth– but he was still effectively current. This was no different than the numerous derivative works inspired by Robert E. Howard’s stories from the 1930’s.

Taking altogether, it’s clear that there was a wide-ranging canon of science fiction and fantasy authors that spanned the better part of a century. The Appendix N list was a quirky subset of these that (by definition) focused on the books that inspired Gary Gygax’s famous fantasy game. But even if he wasn’t representative of fandom in general, his voracious reading habits were certainly held in common with other role-playing game designers of the time, Ken St. Andre and Steve Jackson not being the least of these. Their games were in some sense a culmination of a conversation that had been going on not just for decades, but centuries.

But between the success of these designers, impending changes in publishing, and the dawn of home computers, that was a conversation that was on the verge of coming to an end. Whether the changes were for the better is, I suppose, largely a matter of taste. But in my opinion something surprisingly compelling was lost.

—

¹ It’s Hebrews 6 verses one and two: “Therefore leaving the principles of the doctrine of Christ, let us go on unto perfection; not laying again the foundation of repentance from dead works, and of faith toward God, Of the doctrine of baptisms, and of laying on of hands, and of resurrection of the dead, and of eternal judgment.”

Very interesting point here. How much do you think the dearth of other sources of fantasy/scifi contributed to this? I was in my teens in the 70’s and read most of these books as well, reading Howard/Burroughs/Tolkien in the 60s. Partly because they were available, and really nothing else was. There were almost no films, no TV shows that showed such imagination – books were all for those seeking such fare in that era.

Nowadays, you have fantasy/sci-fi everywhere, and the Internet makes it instantly available. And many RPGs feed off themselves, like D&D and the Forgotten Realms books.

Ah, but the pendulum is swinging back, with the deterioration of the publisher gatekeepers and the rise of Amazon + independents. More is being written and people are starting to rediscover the masters of the last century.

Tangentially, one of the things I’m noticing is that the “psychedelic” era was lagging some 20-odd years behind science fiction. In the last couple months, I’ve already read 3 stories from the 40s set on Mars in which either hallucinogen or cocaine-like stimulant use were major plot points.