RETROSPECTIVE: The Fallible Fiend by L. Sprague de Camp

Monday , 10, August 2015 Appendix N 5 Comments What if demons weren’t monstrous spiritual forces out to corrupt the souls of humans that have dealings with them? What if instead they were rather strong and fairly unattractive… but other than that were just plain, ordinary, upstanding folks? Salt of the earth types, as it were…. And what if there was a reason they had to make pacts with the human beings of the Prime Plane– an entirely mundane thing, too? What if… they would allow themselves to be summoned by magicians and accept a year of indentured servitude in return for ingots of iron– an element which happens to be extremely rare on their home in the Twelfth Plane?

What if demons weren’t monstrous spiritual forces out to corrupt the souls of humans that have dealings with them? What if instead they were rather strong and fairly unattractive… but other than that were just plain, ordinary, upstanding folks? Salt of the earth types, as it were…. And what if there was a reason they had to make pacts with the human beings of the Prime Plane– an entirely mundane thing, too? What if… they would allow themselves to be summoned by magicians and accept a year of indentured servitude in return for ingots of iron– an element which happens to be extremely rare on their home in the Twelfth Plane?

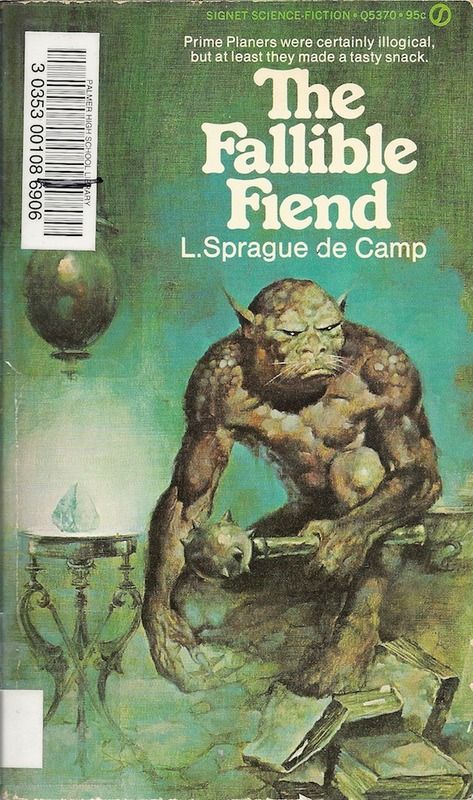

L. Sprague de Camp brings answers to all these questions and more in this short novel– marketed by Signet as science fiction no less. Not that I ever had questions like those on my mind before. I mean… the stuff in this book is the last thing that I expect to read about in all those other books that have covers featuring some wicked looking demonic monster trapped inside a wizard’s pentagram. For a book featuring a demon as a protagonist, precious few of the usual tropes put in an appearance. Nobody goes to a pit of everlasting torment. Nobody gets possessed by demons. Nobody throws up on well meaning clergymen.

But check out this profound wisdom of demon civilization:

- “As we say in my world, perfection waits upon practice.” (page 40)

- “As we demons put it, well begun is half done.” (page 71)

- “As we say in demon land, it is an ill tide that washes nobody’s feet clean.” (page 89)

- “As we say at home, self-conceit oft precedes a downfall.” (page 104)

That’s Poor Richard’s Almanac meets Gaffer Gamgee meets King Solomon right there. And that pretty well sums up demon culture in a nutshell. Oh, they’re scaly, they have emotion sensing catfish wiskers, they have chameleon-like abilities, they’re stronger than they look, and their digestive tupors can last well over a day. But… they’re also monogamous, law abiding, industrious, and honest to a fault. They are Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography… in the flesh.

And next to this guy, humanity comes off as looking pretty shabby. A magician knows through clairvoyance what peril faces a nearby town, but in order to hold out for as much extortion money as possible, he ends up telling them the details only after it is too late for them to do anything about it. A circus owner gives his workers raises, but then wins back their earnings by cheating them at cards. A brigand that takes from the rich and gives to the poor shows promise as being the first truly idealistic person on the Prime Plane… but it turns out he and his crew are the poorest people they know, so they keep all of their loot to themselves.

This sort of thing could have been thought provoking or perhaps provided some sort of comment on the human condition. As it stands, de Camp is merely playing this up for laughs. As the story goes on, the society of demons turns out to be a little too perfect to be believable. They do not practice war and really don’t even have a concept of rape. Meanwhile, the cannibals that are harvesting entire nations for people that they can salt them down for the winter…? To them, they have the moral high ground because their victims are guilty of waging war on each other. In their view, “the only legitimate reason to slay another human being is to eat him.” (page 119)

Unless you really want something over the top, then, you won’t find these cultures to be particularly inspiring for your games. Although there is something to the contrast between the nomads, the cave men, the cannibals, and the more urban peoples detailed here. What’s really useful is how they behave immediately following the big battle. This really is de Camp’s main point with this novel, as the demon character explains:

I have read many of those imaginary narratives that Prime Planers compose for one another’s amusement, which are called “fiction.” We have nothing like this on the Twelfth Plane, being too logical and literal-minded a species to enjoy it. I confess, however, that I have acquired a taste for the stuff, even though my fellow demons look at me askance as if I had become addicted to a dangerous narcotic.

In these imaginary narratives, called “stories”, the human authors assume that the climax of the story solves all the problems posed and brings the action to a neat, tidy end. In a story, the battle of Ir would have been the climax. Then the hero would have mated with the heroine, the villains would have been destroyed, and the leading survivors, it is implied, would have lived happily ever after.

In real life it is different. (page 125-126)

This is of course an indictment against all fantasy and science fiction that followed the Edgar Rice Burroughs style of storytelling. And it’s funny, but The Lord of the Rings falls in line with this through the marriages of Aragorn to Arwen and Faramir to Éowyn. (The Hobbit is actually less cliché on this point, because the death of Smaug does not lead to this sort of standard happy ending. It leads to Bilbo sneaking off with the Arkenstone in attempt to forge peace between men, dwarves, and elves.)

Gamers are especially prone to make the sort of simplifications that de Camp pokes fun at here. Our rule sets are very strong when it comes to resolving conflicts whether they be small scale skirmishes or titanic battles. They are significantly less detailed about how the resolution of one engagement might lead to the next. Even with something simple like what would happen in a dungeon in the weeks following the elimination of a particular faction you’re not liable to get a lot of help from the guides and modules. A good game master pretty much has to arbitrarily take all the variables and incidental bits and frame up a follow up scenario based on little more than sound judgement, common sense, and solid hunch on what would be most fun for everyone in involved.

Players of course are often looking for something that feels like a victory condition to them, even when there isn’t one explicitly engineered into the situation. In fact, players of all kinds of role-playing games will create narratives from completely random things that have transpired in a game and then set off to place themselves within the happy ending that they are sure is to be found in following it up. Half the time, it’s just as well for the game master to accept the player version of game reality, too. It might be better than what he had in mind in the first place, after all! Or it might just be easier to build on their assumptions than it would be to explain what they were “supposed” to see in the first place.

It’s the question of how a series of victories impact a campaign’s overall state that’s particularly thorny, though. And again, there is almost no way for a game designer to anticipate what what a game master would really need to make a fair decision on this. The proverbial “want of a nail” stands ready to rear its head in even the most carefully constructed scenarios.

My advice for dealing with this is to first, take de Camp’s advice to heart. And don’t be afraid ask the players what they think might happen as a result of their actions. For one thing, they are liable to be far more devious than you are. But really, simulating an entire world is too big of a job for one guy anyway. Take everything that’s suggested, take into account the things that the players don’t even know about, and then assign the outcomes an arbitrary chance of happening. Roll the dice… and follow the results wherever they lead– especially if it ruins whatever script you might originally have had in mind.

This is the point where campaigns take on a life of their own: a place where whatever scripts you might have had cease to be relevant and everyone is forced to go off the rails. And even though tabletop role-playing games were inspired by a diverse range of fantasy and science fiction novels, it doesn’t mean that they have to follow the same conventions of genre fiction. In fact it’s the lack of an artificial “happily ever after” moment that’s part of what keeps people coming back for session after session. Out of the box, the classic role-playing games were designed with the assumption that their campaigns would continue on after months of weekly game sessions that could each last well over six hours a piece. And even in this day of innumerable entertainment options and distracting gadgets they are still capable of maintaining that surprising degree of investment and attention.¹ Because even the most subtle aspects of a player’s choices can have unexpected ramifications and not even the game master knows how things will ultimately play out.

—

¹ See Zak S.’s article Why I Still Love ‘Dungeons & Dragons’ in the Age of Video Games for a great piece on this point.

I find it useful between game sessions to see how the various power groups and interests might take advantage of whatever changes the players may have wrought.

So, after a party overthrows a cruel monarch, everyone cheers like a fairy tale ending. When they visit the former kingdom later, they find the terror of the French Republic in full bloom.

You can also have unintended consequences though ignorance. A greedy and cruel dragon could have been guarding the seal to a demon’s prison.

You can also have consequences form direct deception. Desperate to free an imprisoned noble or clergyman, they actually free a demon or anti-paladin. Alternatively, they destroy a noble and virtuous guardian at the behest of a villain with a fake sob-story. I’m especially fond of these, as too many players leap forward without checking things out (and if they figure it out, they can go after the real villains).

Jeffro, thanks for doing these. I don’t comment much, but I really enjoy reading these.