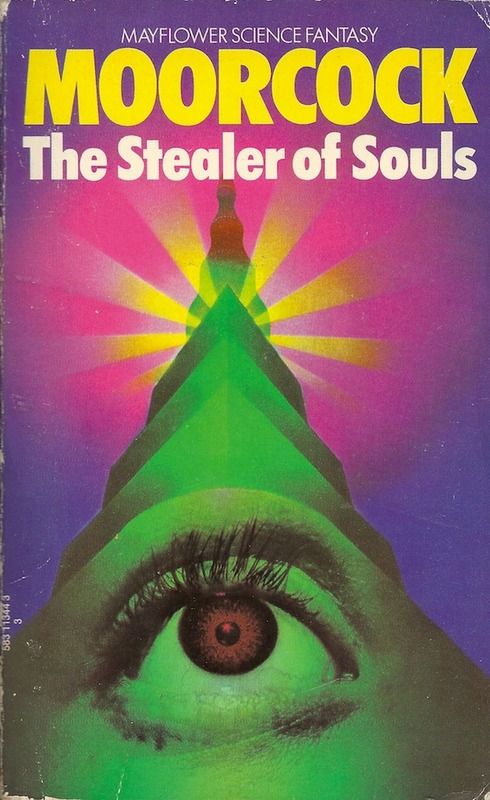

RETROSPECTIVE: The Stealer of Souls by Michael Moorcock

Monday , 17, August 2015 Appendix N 16 Comments Michael Moorcock’s Elric has a tremendous following. And it’s true, there’s a lot here to like. Elric is the quintessential fighting man that can wield both swords and spells. The magic system that’s in force in his setting is based on hereditary pacts with demons and is clearly powered by fatigue points. And the sword Stormbringer is at least as popular as the guy that wields it. After all, it not only gives this frail albino uncanny strength and reasonably clear eyesight, but it also consumes the souls of its victims. What’s not to like?

Michael Moorcock’s Elric has a tremendous following. And it’s true, there’s a lot here to like. Elric is the quintessential fighting man that can wield both swords and spells. The magic system that’s in force in his setting is based on hereditary pacts with demons and is clearly powered by fatigue points. And the sword Stormbringer is at least as popular as the guy that wields it. After all, it not only gives this frail albino uncanny strength and reasonably clear eyesight, but it also consumes the souls of its victims. What’s not to like?

Well, plenty if you ask me.

In the first place, Elric basically a big crybaby. I mean, sure it happens. Peoples’ dogs die. People watch Old Yellar. People read The Lord of the Rings out loud to their kids and end up choking up on scenes that aren’t really even that sad. And sure, we live in the future now. We’re all “free to be you and me”. But somehow, it’s a bit much for an epic hero that acts like he just strode off of the bass clef of a Black Sabbath song to just blubber away right in the middle of the climax of his signature adventure.

But hey, maybe I’m out of line here. Human beings have feelings. Who’s to say that I wouldn’t do the same, right? You just can’t know how well you’d hold up when your navy is attacked by dragons. But it’s not just the fact of his crying that gets to me here. It’s not the timing of it in the context of the plot that’s inducing cringe here. It’s not even his doing it while leading other men in a crisis situation that’s so obnoxious. It’s the reason behind the crying that’s the real problem here.

Quite simply, Elric hates himself. And I can’t really say that I blame him given the circumstances. But this is absolutely a tremendous flaw to put on a protagonist. I mean… we’re supposed to like this character. We’re supposed to want him to succeed. We’re supposed to want to invest in him. But it’s hard to like a character that doesn’t even like himself. And it’s pointless to invest in someone that demonstrates that they’re not worth it right out of the gate.

Here’s how he phrases it when he’s trying to give one of his groupies the brush off:

He paused for an instant and then said slowly: “I should admit that I scream in my sleep sometimes and am often tortured by incommunicable self-loathing. Go while you can, lady, and forget Elric for he can bring only grief to your soul.” (page 41)

And just as you’d expect, the womenfolk of his world completely buy it. They’re drawn in like moths to a flame! I’m really aggravated by this, though– and not just because I’m jealous of Elric’s rock star levels of cachet. After my last Moorcock book, I was all set for something the literary equivalent of “War Pigs”. Instead… I get The Cure.

Why’s he so mopey? Well, let’s put this in terms of The Lord of the Rings just so this is clear. Imagine if Aragorn was a Black Númenórean… and imagine he shows up at Gondor with an army of corsairs. In the process of sacking the place, he kills not only Denethor but Arwen as well. Then in order to escape the chaos alive, he betrays the great mass of his allies in order to flee with the crew of a single ship. That’s basically the Elric origin story in a nutshell. I left out some brooding and stuff, but this is pretty much it.

Granted, the killing of his lady friend was due to his magic sword getting out of hand. And yes, it’s possible to craft a likable antihero that does something like this. All it takes is showing that each group involved is sufficiently despicable that you don’t mind that any of them get their comeuppance. That’s how Jack Vance manged to make Cugel the Clever work– the people he hoodwinked mostly had it coming. He was just a bit more devious in playing at their own games. Of course, Vance took it further and made sure Cugel got his due as well. But Moorcock doesn’t do that. It’s as if he wants to believe that he’s evolved beyond such petty notions such as right and wrong.

Elric betrays people that trust him for little more than a whim. And that’s it. It’s senseless. Yes, he feels bad about the horrible things he’s done. But he doesn’t want to change himself or try to fix anything. In fact, he’s pretty flippant about the whole thing. At one point he’s in another adventure and needs help from his own people– the very ones whose kingdom he’d just helped bring down. They’d gone from living like kings to living hand to mouth because of him. A friend of Elric’s states the obvious about why his former associates might not work out for him:

Moonglum smiled wryly. ‘I would not count on it, Elric,’ he said. ‘Such an act as yours can hardly be forgiven, if you’ll forgive my frankness. Your countrymen are now unwilling wanderers, citizens of razed city– the oldest and greatest the world has known. When Imrryr the Beautiful fell, there must have been many who wished great suffering upon you.’

Elric emitted a short laugh. ‘Possibly,’ he agreed, ‘but these are my people and I know them. We Melnibonéans are an old and sophisticated race — we rarely allow emotions to interfere with our general well-being.’ (page 79)

Yes, a people so sophisticated but which nevertheless have not mastered the idea of “burn me once, shame on you; burn me twice, shame on me.” That’s really hard to imagine, really. Can he actually close the deal? Maybe he has some sort of combination of excessively high charisma, brilliant diplomacy, or even Jedi mind tricks? Let’s see:

‘There should be no contact between you and your people. We are wary for you, Elric, for even if we allowed you to lead us again — you would take your own doomed path and us with you. There is no future there for myself and my men.’

‘Agreed. But I need your help for just one time — then our ways can part again.’

‘We should kill you, Elric. But which would be the greater crime? Failure to do justice and slay our betrayer — or regicide? You have given me a problem at a time when there are too many problems already. Should I attempt to solve it?’

‘I but played a part in history,” Elric said earnestly. ‘Time would have done what I did, eventually. I but brought the day nearer — and brought it when you and our people were still resilient enough to combat it and turn to a new way of life.’ (pages 84-85)

That argument goes over about as well as you’d think. But his countryman ends up getting persuaded anyway. You see, the guy that Elric wants to take down had done something nasty to a Melnibonéan once, so he’s owed payback. Why that would be enough to tip the balance, I couldn’t tell you. (Blood’s thicker than water?) But whether you find him to be a sympathetic character or not, he really is about the worst negotiator in the history of pulp adventure. Consider this exchange:

‘Who sent you here?’

‘Thekeb K’aarna speaks falsely if he told you I was sent,’ Elric lied. ‘I was interested only in paying my debt.’

‘It is not only the sorcerer who told me, I’m afraid,’ Nikorn said. ‘I have many spies in the city and two of them independently informed me of a plot by local merchants to employ you to kill me.’

Elric smiled faintly. ‘Very well,’ he agreed. ‘It was true, but I had no intention of doing what they asked.’

Nikorn said: ‘I might believe you, Elric of Melniboné. But no I do not know what to do with you. I would not turn anyone over to Theleb K’aarna’s mercies. May I have your word that you will not make an attempt on my life again?’

‘Are we bargaining, Master Nikorn?’ Elric said faintly.

‘We are.’

‘Then what do I give my word for in return for, sir?’

‘Your life and freedom, Lord Elric.’ (page 93)

Notice he gets caught in a lie just moments before his life will depend on whether or not this guy will take his word. And all he can do is smile. (Is this what sophisticated people are like?) I can’t imagine why anyone would deal with him for anything. But nobody in these stories seems to care that he will tell lies and break promises whenever it suits him. They keep on trying to deal with him in good faith.

I suppose that whether or not this destroys a reader’s willing suspension of disbelief hinges on the world view of the beholder. I mean, I’ve seen plenty of people rave over these Elric stories, so it clearly doesn’t bother some people. This is one of those things that people will just have to disagree on, I guess. A much easier question would be whether or not this kind of moral incoherence is representative of what goes on in fantasy role-playing games. Certainly the early computerized games do not reflect this. You can steal from store keeps in both Ultima I and Nethack, but if you’re caught, consequences are liable to be both swift and violent. To be sure, the city guards will not be brushed off with a condescending laugh.

The stereotype of the typical tabletop gamer runs towards the “Chaotic Neutral” murder hobo that adventures only so he can kill things and take their stuff. In reality, players are very much concerned with questions of morality even when their personal views on politics and religion would seem to run counter to that. It would be a rare group, for instance, that would fail to argue about the rightness of killing orc babies in The Keep on the Borderlands. Exploring the consequences of whatever the players choose is the stuff of any long running campaign that ventures beyond the routine of, as players put it, “cleaning out dungeons.”

In games like the early versions of D&D which tend to have a high challenge level and high rates of player character mortality, a new factor emerges to cause players to take a different view towards morality than Elric. Success in the game depends entirely on the players’ capacity to cooperate with one another. Nobody plays a superman. “Army of one” tactics ensure not just a greater chance of an individual fool to come to a bad end, but also increase by an order of magnitude the chances of a total party kill.

What this means in practice is that the players’ party as a whole is a fairly rough crowd that, at best, become heroes only in scenarios such as is reflected in The Magnificent Seven. If the players break trust with a king or a non-player character ally, they know that they need to either move on to another domain or else find new friends. And if one of the players fails to behave like a real team player, then when he steps away from the table to get a snack, he’s liable to come back to group that has worked out a fail-safe way to frag him at the very next opportunity.

It is true that men cut from the same cloth as Tolkien’s Riders of Rohan– men who “do not lie, and therefore they are not easily deceived” rarely show up as player characters. And if there is a consensus among gamers, it would be that playing evil is more fun and that good is dumb. (I mean really. Just how often do you see people that are gung ho to play “Lawful” goody two-shoes types?) Nevertheless, there is a certain baseline of trustworthiness that is assumed when it comes to tabletop roleplaying games. The party may be incredibly be diverse and it may be hard to imagine anything that would give the reason to work together like they do, but they always seem to set aside their differences enough that they can cooperate in whatever crazy scheme they get involved with. No, they are not idealists. Like Han Solo, they expect to be well paid.

Elric, though, is another case altogether. In a run of the mill game session, his contempt for loyalty and honesty would get him at best ignored and at worst murdered. Player characters might be rowdy cutthroats, but there is a certain strand of honor among them. Elric’s contempt for it simply would not fly. His short laughs and faint smiles would do little to protect him, either. While it’s not quite true that there is simply no place for a guy like him at the tabletop, a character like him would mostly just provide a nemesis that players wouldn’t feel bad about killing. Players might actually spare the innocent orc babies, sure. But not Elric.

Elric stories are incredibly uneven. The predictability in which his companions die simply because Stormbringer needs to feed gets pretty tiresome, so I couldn’t possibly recommend attempting to Elric as anything other than one or two stories every once in awhile. The good Elric stories are moderately entertaining, if kind of hackish, while the bad are a gouge-your-own-eyes-out mess of awful.

I can’t remember where I read it, but I did read once that Moorcock wanted Elric to be something of an anti-Conan, a reaction to the super-heroic cocksure protagonists of Howard. Something about his being resentful of ‘hypermasculine power fantasies’ or some such. The irony was, Howard already had a thoughtful and introspective barbarian warrior in Kull, but the pulps just weren’t buying that sort of thing back then. So maybe the markets that had forced Conanesque pulp heroes to rise to the top had changed in the psychedelic age to allow for the sort of “anti-Conans” the Moorcock wanted to write.

If Conan was for nerds who wished they were cool manly men, Elric was for nerds who wished they could be cool without being manly.

Cugel works because he’s a classic Trickster; in Trickster stories, sometimes the Trickster win, sometimes, when he bites off more than he can chew, he gets his come-upance. Elric coasts on a combination of absurd luck and mediocre writing until an adventure ends and he can ‘accidentally’ kill whomever he was with for continuity purposes.

Given Moorcock’s well known dislike of Tolkien, I find your use of Aragon hilariously apt…

-

I wonder how much of Moorcock’s present day legacy comes from the fact that he wrote about a race of evil white people who felt they were superior to everyone that they repressed and Elric feels really bad about it.

“we rarely allow emotions to interfere with our general well-being.”

That’s rich coming from Elric the Tear-stained of McBroodybourne?

-

He was the original Emo.

“I should admit that sometimes I scream in my sleep” is Scalzian braggadoccio.

What a Gamma freak.

He should have told her, “I should admit that at some point in the night most women near me scream in their sleep. Don’t worry: it usually is just my thirsty sword.”

just a quick OT request, not sure where to put it.. I bought the e-book version of Lind’s columns, however while reading several of the books he mentioned seemed interesting. I ended up purchasing the Count Duke Olivares for one, but I had to cut-paste-search on amazon. And I also had to go back and search to find the title after finishing the collection. Just a suggestion that new editions contain a bibliography of all books cited by Lind along with an Amazon link.

Well, the Elric stories (and to an extent also Three Hearts and Three Lions) are where the “alignment system” concepts come from.

If there’s a key theme in the series, it’s Elric’s willingness to mess up the alignment system in the novels.

Back in the day – the early 80s – our gaming group loved the Elric novels and we avidly shared them.

Elric’s relationship with gods – he can and does hack them down – probably had a strong influence on early D&D; the Gods Demi Gods and Heroes supplement is very Elric in its treatment of deities as things that fall on the upper end of the spectrum of stuff you can kill, and I think reflects Moorcock’s general view of religion and SF writer sensibilities. Later on we get more politically-correct views infesting the gaming community (“you can’t kill Odin, damn it!”) and the idea of gods as primal forces that treat humans or their kin as cockroaches. But Elric’s attitude is rather more nuanced…

Elric’s moral ambiguity is not atypical of sword and sorcery protagonists – he’s not one of those Aragorn esque High Fantasy types, after all, but rather in the same boat as folks like Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane.

But certainly I found him a more sympathetic character later in the series, especially in the novel STORMBRINGER where indeed he does struggle against villains “a thousand times more evil than thou”

I would also mention that Elric is someone who can ride on a big black horse carrying a big black broadsword while dozens of people shoot arrows at him, and never be struck. He can be surrounded by thousands of armed soldiers and kill them until they are heaped in piles around him and he only stops (completely uninjured) because his soul-sucking sword is so glutted with power that it gets tired.

So, when someone threatens him with death, he can smile because he really doesn’t care. He can afford to be a fatalist, even to seek death and not find it, because that’s how the world works for him.

And this is without even mentioning being one of the most powerful sorcerors on the planet (not the most powerful mainly because he holds back on making new pacts with demons and just uses his family’s old ones).

Elric is not really bargaining. He can’t be forced to do things. Because of his power, he’s all choice, and choices are what make a character.