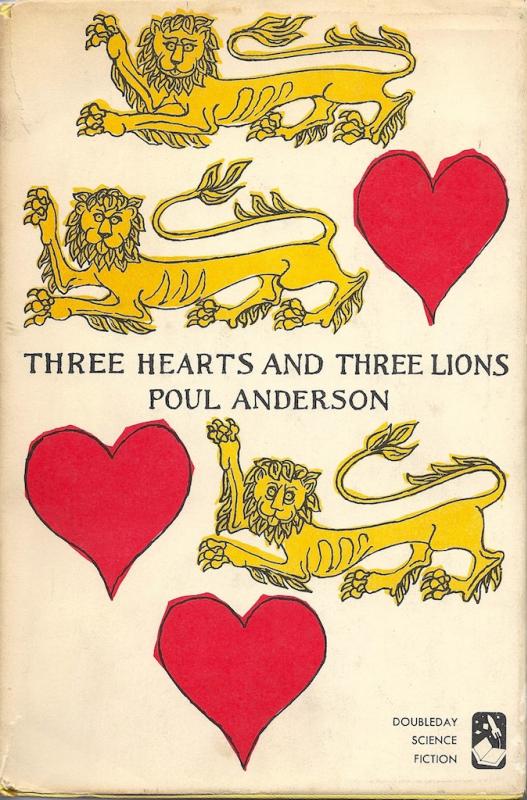

RETROSPECTIVE: Three Hearts and Three Lions by Poul Anderson

Monday , 30, June 2014 Appendix N 19 Comments One reason I enjoy reading the older science fiction and fantasy stories is that they are so much more often free from overt politicization. For a good bad example, look no further than the Next Generation Star Trek episode that has Tasha Yar attempting to explain to Wesley Crusher why it is that people get hooked on drugs. Though she stops short of cracking an egg on an overheated console, it’s still painfully cringe inducing. It was a small mercy to science fiction fans that her character was killed off in the following episode lest we had to endure sermonettes about her disturbing childhood on Turkana IV….

One reason I enjoy reading the older science fiction and fantasy stories is that they are so much more often free from overt politicization. For a good bad example, look no further than the Next Generation Star Trek episode that has Tasha Yar attempting to explain to Wesley Crusher why it is that people get hooked on drugs. Though she stops short of cracking an egg on an overheated console, it’s still painfully cringe inducing. It was a small mercy to science fiction fans that her character was killed off in the following episode lest we had to endure sermonettes about her disturbing childhood on Turkana IV….

The original series actually topped that in “The Omega Glory” when Kirk harangued the bible-clinging, flag-venerating Yangs over their parochial views of the constitution: These words and the words that follow were not written only for the Yangs, but for the Kohms as well! Yes, after dealing with a disastrous violation of the prime directive on a war torn world, Kirk pretty much can’t leave the planet without making that point that “inside every gook there is an American trying to get out.”¹ It’s almost surreal.

This sort of sanctimonious “after school special” type of approach to storytelling is bad not just because it is so transparent and ham-handedly implemented. It’s bad because it displaces deeper and truer things: things that induce wonder and that have the capacity to thrill the soul. In the attempt to be “relevant” or topical, it’s all too easy to sacrifice timelessness. It’s not just the odd scene that’s off the mark either– the entirety of the plot is often structured in such a way as to deliver these ludicrous punchlines. It’s a waste, reducing what should be epic adventure down to the level of shaggy dog story.

It’s surprising just how different golden age literature can be from this. Humanity, for instance, was not always portrayed as being destined to succumb to a self-induced apocalypse. Going further back in time, you’re so much more likely to find the sort of muscular, “can do” attitude that put men on the moon. While this occasionally borders on hubris, I personally wouldn’t mind seeing our manifest destiny to the stars make a comeback. Similarly, in fantasy in the days before the influence of countless Tolkien imitators you were so much more likely to find a sense of alien wildness to the faerie elements. Across all genres you could find traditional notions of vice and virtue that could lend a mythical or even parabolic tone to the works that portrayed them.

Poul Anderson’s 1961 novel Three Hearts and Three Lions is perhaps unique in that it successfully knits all of these things together into a particularly satisfying package. This is possible because it’s a fairy tale wrapped within a frame of science fiction. The protagonist is whisked from the midst of a World War II skirmish and thrust into a fantasy world. He turns out to be a figure of some importance there, but he lacks the necessary memories to function intelligently in the new milieu. Though he retains fragmentary knowledge of the nature of his otherworldly abilities, it turns out that his mastery of reason and basic science facts are the key to getting him and his new found friends out of the trouble that he blunders into time and again. While it occasionally comes off a bit pat, it is nevertheless good fun; the payoff at the end is certainly worth hanging around for.

Of course, a number of people are going to be reading and recommending this book because it is the literary antecedent of the paladin class from the first edition AD&D Player Handbook. Certainly, the laying on of hands, the warhorse, and the “Holy Sword” are all here. The biggest discrepancy is that Gygax made the “protection from evil” ability always on and primarily benefiting the paladin himself. Poul Anderson actually has it being much more powerful and protecting the party’s entire camp if certain preparations are followed, though it can be spoiled if the paladin so much as curses or entertains impure thoughts. The latter could be hard to avoid given the alluring nature of the various elf women, nymphs, and evil sorceresses that are on the prowl…!

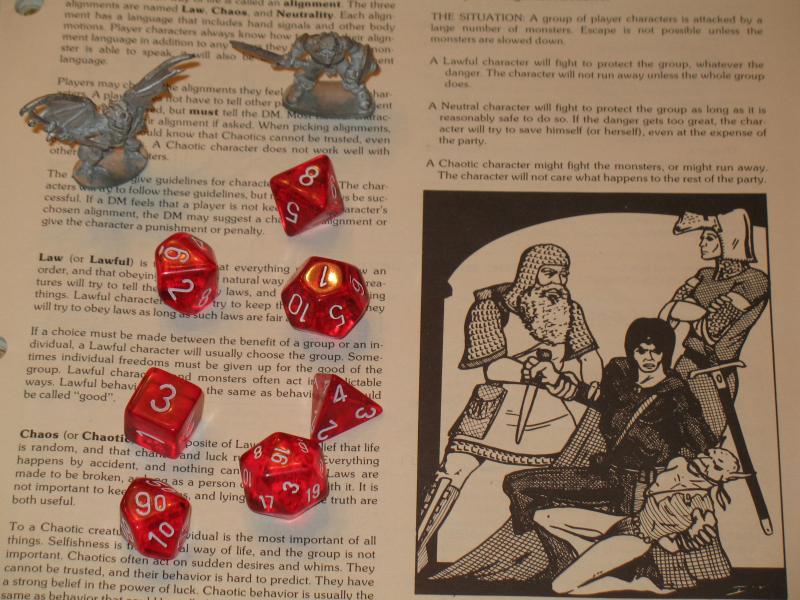

Less often remarked upon is the fact that this book is the source for the alignment system of Basic Dungeons & Dragons. For those that have no experience with tabletop role playing games, I may be unable to convey just how strange and divisive this element really was. You see, in what tended to be a vaguely naturalistic setting, players in the game would set forth into the wilds to kill monsters, win treasure, and evade diabolical traps. But for some reason, Gary Gygax felt it necessary to demarcate what was essentially the spiritual allegiance of every character, monster, and plane of existence in the game. When other designers tried their hand at the medium, this was often the first thing they eliminated, but it remains an integral part of gaming culture to this day. And while the earlier war game crowd that pushed lead figures on the sand tables in their basements tended to behave more like supreme court justices whenever they had to resolve a rules dispute, role playing gamers often ended up becoming small time theologians or moral philosophers because of the innumerable issues alignment inevitably brought into play.

Less often remarked upon is the fact that this book is the source for the alignment system of Basic Dungeons & Dragons. For those that have no experience with tabletop role playing games, I may be unable to convey just how strange and divisive this element really was. You see, in what tended to be a vaguely naturalistic setting, players in the game would set forth into the wilds to kill monsters, win treasure, and evade diabolical traps. But for some reason, Gary Gygax felt it necessary to demarcate what was essentially the spiritual allegiance of every character, monster, and plane of existence in the game. When other designers tried their hand at the medium, this was often the first thing they eliminated, but it remains an integral part of gaming culture to this day. And while the earlier war game crowd that pushed lead figures on the sand tables in their basements tended to behave more like supreme court justices whenever they had to resolve a rules dispute, role playing gamers often ended up becoming small time theologians or moral philosophers because of the innumerable issues alignment inevitably brought into play.

More than that I cannot say without being ponderously obscure. At any rate, you will find in Three Hearts and Three Lions the basis for the original three point alignment system of Gary Gygax’s famous and influential game. What we see here is so different from what role players take for granted that it can be positively staggering to people that grew up with the game.

At one extreme, we have Chaos… which here is not always synonymous with evil. As its name would lead you to believe, it really does actually does have elements of random unpredictability to it:

You canna tell wha’ the Faerie folk will do next. They canna tell theirselves, nor care. They live in wildness, which is why they be o’ the dark Chaos side in this war.

The alignment most preferred by the typical adolescent role player is Neutral and here it turns out to be a bit more cranky and cynical that what we see in, say, the attitude of Treebeard from The Two Towers:

We’ll ha’ naught to do wi’ the wars in this uneasy land. We’ll bide our aine lives and let Heaven, Hell, Earth, and the Middle World fight it oot as they will. And when yon proud lairds ha’ laid each other oot, stiff and stark, we’ll still be here. A pox on ’em all!

And Lawful is more of a combination of mundanity, civilization, and (surprisingly) Christianty:

Holger got the idea that a perpetual struggle went on between primeval forces of Law and Chaos. No, not forces exactly. Modes of existence? A terrestrial reflection of the spiritual conflict between heaven and hell? In any case, humans were the chief agents on earth of Law, though most of them were so only unconsciously and some, witches and warlocks and evildoers, had sold out to Chaos. A few nonhuman beings also stood for Law. Ranged against them was almost the whole Middle World, which seemed to include realms like Faerie, Trollheim, and the Giants– an actual creation of Chaos. Wars among men, such as the long-drawn struggle between the Saracens and the Holy Empire, aided Chaos; under Law all men would live in peace and order and that liberty which only Law could give meaning. But this was so alien to the Middle Worlders that they were forever working to prevent it and to extend their own shadowy domain.

Contrast this with Tom Moldvay’s edit of the original D&D rules: Lawful is characterized there as being predictable and having a concern for the group over the individual. Chaos is about selfishness and capriciousness. The crucial element that has been dropped from this spectrum is not the Gygaxian good/evil axis of AD&D, but rather the influence of Christianity and Faerie at either extreme:

In olden time, richt after the Fall, nigh everything were chaos, see ye. But step by step ’tis been driven back. The longest step was when the Savior lived on earth, for then naught of darkness could stand and Pan himself died. But noo ’tis said Chaos has rallied and mak’s ready to strike back.

Here, Christianity is antithetical to Faerie magic. Elves cannot touch iron, cannot bear the sight of a crucifix, and are physically hurt when the name of Jesus is invoked. Neutral creatures of the middle world are often fantastic: they lack magical abilities, but they have “no fear of iron or silver or holy symbols.” Incredibly, the influence of the Law/Chaos spectrum spills over into the physical geography of Poul Anderson’s fantasy world:

Well, you see, the world of Law– of man– is hemmed in with strangeness, like an island in the sea of the Middle World. Northward live the giants, southward the dragons. Here in Tarnberg we are close to the eastern edge of human settlement and know a trifle about such kingdoms as Faerie and Trollheim. But news travels slowly and gets dissipated in the process. So we have only vague distorted rumors of the western realms– not merely the Middle World domains out in the western ocean, like Avalon, Lyonesse, and Huy Braseal, but even the human countries like France and Spain.

The impotence of Chaos in a direct confrontation with the faithful and the pure of heart means that it must adopt a multifaceted strategy in undermining Law. As a consequence, we see a threat that is quite different from the orc armies of Sauron and his wraithish minions:

Chiefly, methinks, the Middle World will depend on the humans who’ll fight for Chaos. Witches, warlocks, bandits, murderers, ‘fore all the heathen savages o’ the north and south. These can desecrate the sacred places and slay such men as battle against them. Then the rest o’ the humans will flee, and there’ll be naught left to prevent the blue gloaming being drawn over hundreds o’ leagues more. With every advance, the realms o’ Law will grow weaker: not alone in numbers, but in spirit, for the near presence of Chaos must affect the good folk, turning the skittish, lawless, and inclined to devilments o’ their own…. As evil waxes, the very men who stand for good will in their fear use ever worse means o’ fighting, and thereby give evil a free beachhead.

This is utterly fantastic. And yet, it also rings true. For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.² The contrast between hearing that idea in a homily and getting the exact same thing in an adventure story is stark. And yet non-Christian readers don’t seem to feel lectured to when they come to these passages any more than they do when they read how Sam carried Frodo up the slopes of Mount Doom³, or when the wise turned out to be far less effective than a few rustic hobbits.⁴ When telling a story, neither Tolkien nor Poul Anderson need ever mount a soap box in order to get their point across. They inspire rather than insult their readers precisely because they leave their readers the freedom to determine actual applicability of the message.

In like manner, Gary Gygax stripped off the post-apocalyptic elements of Jack Vance’s magic and the Christian and Faerie aspects of Poul Anderson’s alignment structure so that dungeon masters could far more easily adapt these systems to diverse campaign worlds of their own creation. This Frankenstein’s monster approach to game design lends Dungeons & Dragons a depth that its competitors often lacked even if it was often hard to understand by players that were unfamiliar with the literary sources. Nevertheless, this is how things are done when creators actually trust their audiences to read and interpret for themselves. It’s a pity that such confidence is the exception now rather than the rule.

—

¹ This astounding assertion was immortalized in Stanley Kubrick’s 1987 film Full Metal Jacket.

² Ephesians 6:12.

³ Bear ye one another’s burdens, and so fulfil the law of Christ. (Galations 6:2)

⁴ But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty. (1 Corinthians 1:27)

Yes, but Gygax also created one of the most critical basic vocational classes in gaming:

The Cleric. It may have been my DM or it may be my addled memory, but I remember the Village of Hommlet in the very early days being a Catholic town, and the cleric in our party praying to St. Anthony or somesuch.

I would say that D&D provided my first introduction to Christianity as it may be practiced, rather than what I believed it to be.

I wonder how much of Anderson’s design structure in alignment simply can’t be divorced of its Christian compass.

The one module I remember failing at (as a DM) was Ravenloft. I believe it is because I could not grasp the nature of Strahd’s evil. He came off like a bothersome imp (again, because of me.)

One thing I’ve learned from that (and Stoker’s Dracula, and Newman’s Anno Dracula) is this pun:

When you are talking about vampires, the stakes are Christ. No Christ, destroyer of idols…no story.

Same with the alignments. Lawful Evil describes the Pharisee, and nothing else.

-

It may interest you to know that the cleric’s Holy Symbol really is a crucifix. (I always thought it was a made up Gygaxian term that was intentionally decoupled from Christianity, but that is not the case as this book reveals.)

-

Not only did I not know that, but I remember very clearly having an image in my mind of how stupid it was to “turn undead” with some runic idol instead of a cross…and this was when I was an atheist. For whatever reason, I always liked the fact that Van Helsing and Father Karras were inheritors of Christian power, even if the truth of that power made me queasy if I thought about it too long. It just seemed stupid to shout “The power of Sheelba of the Eyeless Face compels you!” or whatever.

Even in my fully materialist adolescence, I wanted my Clerics to be Men of God, and fully convicted…same with Paladins, a class I hated and never played because it was nearly impossible to play them as anything but earnest and devoted Christian Crusaders. Many years later I happened to be playing a fairly generic (and horribly disfigured) cleric around the time I experienced conversion.

Shallow as it may seem, coming into relationship with the Lord Almighty had the trivial side effect of improving my role-playing immensely. “Jesus makes D&D better” is a terrible notion, I know, but he certainly doesn’t make it worse!

-

If I recall, most of Holmes’ clerics were certainly of the Catholic faith, invoking their divine powers with Latin incantations.

-

-

Note for clarity: I was an atheist back then. I don’t mean to recommend Dungeons and Dragons as a catechism!

You remind me of Richard Garriot’s alignment based in virtues for Ultima. I wonder if he may have been influenced by Poul Anderson (but more probably was by Gygax.)

-

Garriot striked me as not being nearly as well read as guys like Gary Gygax, James Ward, and Marc Miller.

You know, I can’t help but feel like some of the strangeness of the scenarios in early D&D come from the conflict between the Tolkienian paradigm and what you’ve described in this book. The Caves of Chaos as a threat to the Borderlands makes sense if its inhabitants are aligned with chaos as creatures of Fey encroaching on the lands of good christian men. But if they are simply other races, representing no threat other than what a slightly less advanced culture on the borders of a more advanced culture tend to represent, the moral and existential threat is significantly negated.

-

Yes exactly. This book explains also why the humanoids in B2 are so disorganized, why there is no Sauron-like figure directing them, and why things get wild and wooly once you get on the outskirts of the Realms. It makes so much more sense now. Bonus: you also know what will be accomplished if the Priests of Chaos are left to themselves to do their dirty work. The twilight will be extended and the Keep will face a certain attack from the Cave denizens after farmers flee and treachery is worked from within…!

It’s been a very long time since I read Three Hearts and Three Lions, a great book. But when I first played D&D (1975) I assumed the alignment system came straight out of Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion series (Elric, Hawkmoon, etc.). Blatantly. I don’t recall much of 3H&3L, certainly not any explicit alignment.

Anderson’s fantasies are certainly more related to the older pre-Tolkien stuff than to Tolkien. Faerie as danger, another world adjacent to ours.

-

Thanks for dropping by in this venue, Doctor Pulsipher.

I have not yet read Moorcock. I really look forward to seeing what that is all about!

-

A word of advice if you try to read the Elric Saga: try to read it in publication order, rather than chronologically. I tried reading the classic box set and got bogged down and burned out reading the side-stories and short stories that had been edited into novels that I stopped before I read THE Elric story, since it was last chronologically.

-

Btw, in the late 60s when I first corresponded with him, and I think during development of D&D, Gary Gygax was a Jehovah’s Witness (later lapsed, I think).

-

“when I first corresponded with him”

Okay, that is not a story I have heard. (!!)

-

Gary was a co-founder of the International Federation of Wargaming. In 1966 (I was 15) I wrote to him about something-or-other in connection with the club. I specifically remember him saying “don’t call me Sir, I’m not old enough for that”. Sigh.

-

As long as we’re name-dropping, I used to have (and may still have) a letter from Dave Arneson describing his campaign that resulted ultimately in D&D. (I was publishing a sf/f game fanzine, “Supernova,” at the time.) Never met Dave, only met Gary briefly. Though my brother had an adventure in Castle Greyhawk at one of the GenCons that were still in Lake Geneva (I wasn’t there). Gary showed a drawing of a staircase as they entered. They checked it out, found a secret door, encountered some monsters or a trap. Gary said that in the original play, the players had passed the place dozens of times without checking. That was when the mystery was all-new.

Lewis, do you know why the big names in old wargaming and rpgs died off at the rate of 1/year for 7 years at the beginning of Spring?

Moldvay died in March 2007

Gygax in March 2008

Arneson in April 2009

Holmes in March 2010

Roslof March 2011

Barker March 2012

Vance in May 2013

I just want to know who missed the saving throw, and, more importantly who cast it in the first place?

Having grown up a Witness and having d&d treated as the Devil’s Own,, it shocked me when I found out he was a Witness. Has anyone done a biography yet?

-

The person that has done the most to tell the story of Gary Gygax and how he developed his game is Jon Peterson of Playing at the World.