Short Reviews – Three Lines of Old French, by A. Merritt

Friday , 22, December 2017 Uncategorized 7 CommentsThree Lines of Old French by A. Merritt originally appeared in the August 9, 1919 issue of All-Story Weekly. It was reprinted in the February, 1950 issue of A. Merritt’s Fantasy Magazine, and can be read here from Archive.org.

AMFM Follows up The Smoking Land with the A. Merritt short story “Three Lines of Old French”, and I’ve got to say, I really enjoyed it!

Dangerous confession time: prior to this, the only A. Merritt story I’d read was The Metal Monster. I’d found The Metal Monster ambitious and fascinating in what it set out to try to convey, but ultimately it dragged as Merritt struggled to describe in great detail the inconceivable (a race of beings that pretty much resembled Vector Man, only gargantuan). I’d been hesitant to check out his other work, because it took me so long to finish MM. Three Lines of Old French has made me re-evaluate and put Merritt back in the priority list.

Here, he masterfully conveys scene and imagery and powerful emotion in a relatively short space, telling a war story that transcends notions of horror and fairy tale and science fiction, teasing at darkness and nihilism while the true bait-and-switch promises love and hope.

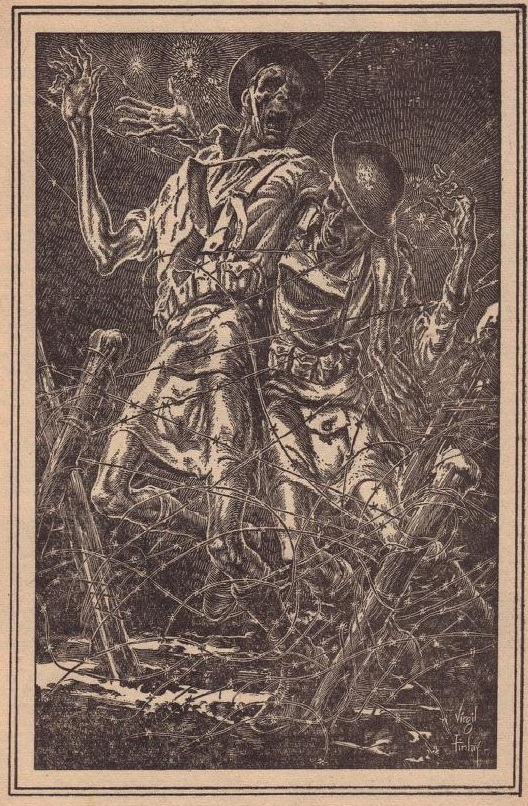

A soldier in the trenches during World War One stares out across the trenches, keeping watching. Barely on the edge of conscious, cognitive thought, his mind is weakened and frayed into a near hypnotic state from extreme fatigue, the flashing lights of tracer shells and flares, and the rhythmic gyrations of corpses caught in the barbed wire of no-man’s land.

The story is recounted, to a group of scientists and physicians, of the seemingly impossible events that transpired in the blink of an eye to Peter Laveller, now deceased. A surgeon had wanted to conduct psychological experiments on soldiers who were at a mental breaking point, in this case planting a suggestion in young Laveller’s mind by simply waving a few words in front of his eyes, allowing his subconscious to fill in the gaps.

And fill in the gaps it does! Peter wakes up in a pleasant field near what must certainly be the chateau just a short way from the trenches in the even more pleasant company of a young lady, Lucie de Tocquelain. He doesn’t know whether he’s dead, sleeping, or if the war is over and he’s suffering flashbacks.

The story presents a visceral look at subjects like PTSD and Shell Shock, dissociative episodes in which one cannot tell what is real and what is not. Is Peter really with Lucie or is he in the trenches? Has he fallen asleep and failed his comrades, or is war in the past, behind him, haunting him? When he leaves, Lucie sends him back with a token of her love and the truth of their moments together, but Laveller is confronted by the doctor who claims credit for the experience—it becomes too much for him that so real and pure an experience, and the promise of life after death and a time and place of peace after all of the killing might be nothing more than a lie of the mind.

Laveller nearly kills the surgeon, he’s been so shaken from his reverie, but after being restrained, collects himself and apologizes. Thinking it has all been a trick of his mind, Laveller pulls the scrap which the surgeon had held in front of his face and placed on his person—over the lines of poetry the surgeon had shown him were written:

Nor grieve, dear heart, nor fear the seeming—

Here is waking after dreaming,

She who loves, Lucie

The storyteller concludes his story, and one of his fellows insists that perhaps the surgeon had not noticed the lines written on top of lines, maybe they were too faint. No! the storyteller reveals, for HE was that surgeon! The implication, of course, is that Laveller had faith in life after death and that he would see his love again, and thus, after a brief convalescence, was able to return to the front and fight and die bravely with his comrades, for he was surely reunited with his Lucie in death. And Lucie truly had written those lines for him, present now in defiance of all reason across space and time.

It’s almost a meme in our circles that Merritt’s writing transcends genre and in his time the line between fantasy and science fiction was much blurrier, but he really hits all of the notes in this story: the sort of macabre and visceral horror that you get from a Poe or a Lovecraft, the nearly gothic fairytale fantasy of the pure, ghostly lover, and the mad science of manipulating the psyche of soldiers at war to create false experiences. In this story, much more than The Metal Monster, do I see Merritt’s influence of Lovecraft, CL Moore, and a whole host of other pulp writers.

Merritt himself was ambivalent about THE METAL MONSTER. It is definitely, as a novel, more about the titular monster and the concepts it embodies than about the human characters in the tale. HPL pointed this out early on. That said…what a concept! Lovecraft is on record numerous times praising the breadth and depth of Merritt’s cosmicism in that story. There is also the (unproven)possibility that TMM influenced Transformers.

THE METAL MONSTER and “Three Lines…” demonstrate Merritt’s vast imaginative and literary range in the pulp SFF/”weird” field, a range that I don’t think was ever quite equaled by even such titans as ERB, HPL or Howard, at least in some respects.

Merritt never repeated himself. Each of his tales, short or long, is distinct from all the others. If you’re looking for your next Merritt novel, I would suggest THE SHIP OF ISHTAR (the Paizo edition is best in many ways). It was voted the best story by the readers of Argosy versus competition by stalwarts like ERB and stretching back 45 years. For a short tale, check out “Women of the Wood.” It was voted “best story ever” by the readers of Weird Tales.

To read virtually all of Merritt’s work online, I recommend Glashan’s site:

http://freeread.com.au/@rglibrary/AbrahamMerritt/AbrahamMerritt.html

Only Merritt story I’ve read so far was “Through the Dragon Glass.” It was good, but didn’t wow me and I’ve been similarly hesitant to prioritize him in my reading queue. Still, this is a good reminder that I need to get back to him soon.

-

“Through the Dragon Glass” was Merritt’s very first story ever published. Using it as a benchmark is like holding “Spear and Fang” against Robert E. Howard. That said, I find it a good little yarn. A pity he never completed the implied sequel.

Merritt’s short tales are a little more uneven than his novels, IMO, though it has to be pointed out that many of his “novels” were originally pulp short stories and novellas stitched together.

-

It’s a good story, but Merritt got better as he went. I would definitely recommend his novels.

“The Metal Monster” was the first Merritt I read, and didn’t impress me much either. I’m glad I gave him another chance, because “The Ship of Ishtar,” “Dwellers in the Mirage,” and “Women of the Wood” are among the greatest things I’ve ever read. Anyone who passes those up is doing themself a great disservice.

Three Lines of Old French makes an impression no easily forgotten.

I second deuce’s recommendation of The Ship of Ishtar as your next read of A. Merritt’s work. That’s the one I tell anyone to read if you’re only going to read Merritt once.

Just finished reading this tale. Great review, I also how Merrit uses the framing device which is a bunch of people belonging to a Science club or Explorers club discussing or investigating a case.