This is a piece that I wrote 12 years ago for a collection of essays on Lin Carter with the horrible title of Apostle of Letters. Maybe 30 copies of the book were sold. There were some good essays in the book and some not so good essays. Anyway, I make the case there was a Lin Carter style underneath his pastichery:

It is often said of Lin Carter that he lacked his own style and diligently imitated other writers. A closer examination of his fiction reveals that Carter did develop a style for the earlier portion of his career. Carter’s introduction to his 1969 Beyond the Gates of Dream collection included some autobiographical material about what he read while growing up. He absorbed the Oz books and Edgar Rice Burroughs at an early age and followed up with a generous helping of 1940s pulp magazine fiction such as Doc Savage, Leigh Brackett, A. Merritt, and Famous Fantastic Mysteries. Other forms of popular culture such as radio shows, movie serials, and comic books also helped to shape the author-to-be.

Carter’s writing career did not take off immediately. Some shorter fiction and poems appeared in fanzines from 1948-1952. He managed to sell a story (“Masters of the Metropolis”) co-written with Randall Garrett to the prestigious Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (April 1957) during the editorial tenure of Anthony Boucher, founder of the magazine. But it took the Edgar Rice Burroughs paperback boom that began in 1962 to provide a definitive launch for Carter’s writing career.

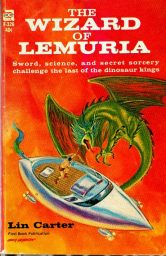

The Wizard of Lemuria (Ace Books, 1965) was not Carter’s first novel, but it was the first to be published. Wizard introduced Thongor of Lemuria as the hero center stage and offered much of what readers would come to recognize as the Lin Carter style. Edgar Rice Burroughs was the most readily apparent influence on Lin Carter’s plotting and prose in this and subsequent books.

The Wizard of Lemuria (Ace Books, 1965) was not Carter’s first novel, but it was the first to be published. Wizard introduced Thongor of Lemuria as the hero center stage and offered much of what readers would come to recognize as the Lin Carter style. Edgar Rice Burroughs was the most readily apparent influence on Lin Carter’s plotting and prose in this and subsequent books.

Carter’s Lemuria combined elements of Burroughs’ Barsoom and Pellucidar, only a Robert E. Howard-style barbarian stalked across the resulting continent. Thongor is probably Carter’s best-known character, larger than life and more heroic than most he would create. Carter describes Thongor in this passage from The Wizard of Lemuria:

“A bronzed giant, naked save for leather clout and black cloak, standing atop the parapet, a longsword in his hand. Golden eyes blazed in a clean-shaven face, and a long, wild mane of black hair fell to the naked shoulders.” (p. 18)

Against a backdrop of the lost continent of Lemuria, located in an area now occupied by the Pacific Ocean 500,000 years ago, Thongor, a mercenary from the wintry northland of Valkarth, kills a superior officer in a duel over an unpaid wager. Imprisoned, he escapes through the aid of a friend and steals a prototype airship. The craft is attacked by a giant “lizard-hawk” and, damaged, subsequently crashes into the jungle. Sharajsha, a wizard with uses for a swordsman of Thongor’s prowess, aids the barbarian and repairs the airship. He means to enlist Thongor on a quest to defeat a conspiracy by a remnant of the Dragon Kings. The Dragon Kings once ruled all of Lemuria millennia before and plan to retake the continent from humankind when the stars are right. Along the way, Sharajsha and Thongor steal a star stone in order to forge the Sword of Nemedis, a weapon that acts as a talisman of power against the Dragon Kings. There are various adventures including rescuing the captive Princess Sumia. Thongor is a man of action:

“Therefore, he sprang, taking the spearmen off guard. From complete immobility he flashed into action. Whirling on his heel, he leaped at the first spearman, felling him with a straight-armed blow to the jaw and wrenching the long spear from his slack hands. Whirling again, he charged at the dais. A guard interposed, but Thongor ran him through the belly and the man fell, clutching with numb hands at this tumbling guts. In a flash he was up the marble steps Drugunda Thal was rising to his feet, features working with terror. Thongor swung the steel base of the spear at his head, knocking the Sark sprawling.”

Thongor destroys the Dragon Kings with the magic sword, which becomes an energy weapon when activated. This was a plot Carter would repeat- a rugged adventurer falling into a quest with a older mentor/wizard/scientist who provides arcane knowledge to foil a conspiracy to conquer the world (or galaxy). A beautiful princess or slave girl is generally saved along the way; sometimes an evil femme fatale is part of the story to tempt the hero. Providential divine or semi-divine intervention is required to defeat the villain at the novel’s climax. Carter was fond of using magic weapons, talismans, and amulets, many of which resemble what The Encyclopedia of Fantasy terms “plot coupons.” His heroes rarely thwart the conspiracy by their own strength or intelligence. Intervention by a higher power saves the day again and again, but also detracts from the heroism that is of course a hero’s reason for being.

The Wizard of Lemuria did not meet with approval in all quarters. A review in Amra V2 #36 (Sept. 1965) by Archie Mercer stated, “The only such distinguishing feature I am able to discern in The Wizard of Lemuria is that it is entirely derivative of other works in the genre, with no obvious originality whatsoever.”[1] In the same issue of Amra, Harry Harrison said

“He has done such an incompetent job that for a few moments there I though he was writing a parody of swordplay-and-sorcery…Why does this book offend me? Because there is not an ounce of originality in it. The people, machines, names—everything has been assembled out of an old box of Burroughs and Howard fragments.” [2]

Harrison went on show some examples of inconsistencies and summed it up at the end with

“Am I being cruel? Perhaps. But Lin Carter was cruel to me. He promised me an ‘action packed novel’ with ‘vivid sword-and-sorcery impact’ and he did not deliver. I read his book and I was not satisfied. I wish he would go away and think about what I have said, then sit down and try to write a more consistent and interesting book of his own.”[3]

Neither abashed nor deterred, Carter followed in 1966 with Thongor of Lemuria and The Star Magicians, both of which were published by Ace Books. Thongor of Lemuria was a direct sequel to The Wizard of Lemuria and continued the adventures of Thongor on the path to empire and more sequels. Carter managed to bring in a fair amount of sword-and-sorcery props to the space opera genre with The Star Magicians. Reading Lin Carter’s space opera reveals influences by Isaac Asimov’s Foundation stories, Poul Anderson, Frank Herbert, Gardner Fox, and Robert Silverberg among others. Commendably, Carter gave galactic empires a sparkle generally associated with sword-and-sorcery fiction in his space opera novels. Swords are used as much as blasters, and the reader is never quite sure if sorcery or pseudo-science is at work.

There was no single over-riding influence on Carter’s space opera that one can pick out as with his individual fantasy novels. The Star Magicians has a rampaging horde of galactic barbarians (The Varkonna) plundering world after world. Calastor, an agent from the planet of the Star Magicians, infiltrates the Varkonna horde attempting to stop their tide of conquest. The Star Magicians preserve the science of the former Carina Empire and work for a rebirth of learning. Calastor’s identity is exposed but he escapes the Varkonna with Lurn, a princess in hiding. The two strive to foil the Varkonna horde and the end of the novel climaxes with the Green Goddess dealing justice to the leaders of the Varkonna. Carter’s writing ability improved with each novel during this period and The Star Magicians was an enjoyable adventure.

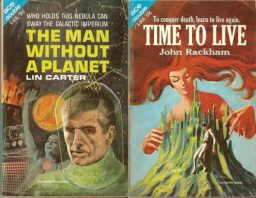

The Man Without a Planet (Ace Books, 1966) was even better. Like The Star Magicians, The Man Without a Planet was an Ace Double novel, that is two novels were bound together within one book. Each novel had a front cover at each end of the book. You flipped the book over and upside down when done reading the first novel to read the second. Planet has a galactic empire setting and written in a fairly tough manner. Carter mixed exotic atmosphere with the hard-boiled narrative:

“Here went a chieftain from Arkonna, his pointed beard dyed indigo, jewels dangling from his stiffly-waxed mustachios. And there strutted a mercenary swordsman from the Orion Stars, if his green-gold cloak and wheat-blond hair were any sign. There a cowled crimson-robed Star Scientist paced with shaven skull, thumb holding his place in a leather bound Ephemeris, the constellations of his nativity tattooed in blue ink on his naked brow.”

Ex-naval officer Raul Linton has quit military service and becomes involved in saving a planet from destruction at the hands of a corrupt governor. There is no indication of overwhelming influence from other writers in this novel. The writing is tight and the characterization is a step above the usual Carter novel. He was handily incorporating fantasy props within the framework of a space opera novel and making it a trademark of his style. With space opera, Lin Carter seemed to be more relaxed and less constricted, not nearly as far under the shadow of writers he emulated.

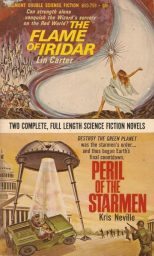

The Flame of Iridar (Belmont, 1967) would be familiar in plot and character to readers of Thongor. This novel was a mix of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, and Leigh Brackett. Iridar is Mars ten million years in the past. Chandar, the heir to conquered Ormsgard, escapes the slaughter of his family and people by King Niamnon of Shiangkor. He grows to be a pirate and scourge of Shiangkor striking at Niamnon every chance he gets. The novel opens with Chandar captured after a sea battle and thrown into the dungeon. Sarkond the Enchanter releases him in return for his assistance in seeking out the Flame of Iridar using his axe, the Axe of Orm. The Axe of Orm has magical properties and is one of three arch-talismans of Iridar.

Sarkond uses an airboat to travel to the enchanted city of Iophar in the polar region, hoping to gain power from the Flame of Iridar. Wizard and warrior discover the Flame, a disembodied intelligence that renders judgment on all—just like the Green Goddess in The Star Magicians. The Flame magically transports Chandar back to Shiangkor to confront Mnadis, Red Witch of K’Thom, who has another arch-talisman and is a minister of the Dark Flame, an opposite entity to the Flame. There is a climactic battle between the two Flames while Chandar uses the powers of Axe of Orm, which shoots bolts of fire to first cut down Niamnon’s guard. Chandar uses the Axe against the Dark Flame in a similar fashion to Thongor using the star-blade against the Dragon Kings.

Lin Carter was given the job of finishing three Robert E. Howard fragments for King Kull (Lancer Books, 1967), and the resulting stature-by-association helped to establish him in the forefront of the sword-and-sorcery fiction boom of the 1960s. As a junior partner of L. Sprague de Camp in 1967, he began plotting and writing new Conan adventures for the Lancer paperback editions. Carter created a story, “The Hand of Nergal,” out of a fragment left behind by Robert E. Howard. L. Sprague de Camp had been unable to do anything with the fragment having not a synopsis for the story. The other incomplete Conan stories by Howard had outlines that enabled de Camp to finish them. The end product of “The Hand of Nergal” was very much a Lin Carter story, as Conan becomes a bystander while two magic talismans battle it out. Carter claimed to have written “The Hand of Nergal” after carefully studying Robert E. Howard’s style and storytelling but the upshot of all that study was very Carteresque with the name Conan instead of Thongor inserted.

Carter appears to have been the creative half of the de Camp-Carter writing team, providing story ideas to be converted into Conan stories. According to Robert M. Price in Lin Carter: A Look Behind His Imaginary Worlds (Starmont Books, 1991), many of the Conan stories written by de Camp & Carter for the Lancer Paperbacks were originally meant to feature Thongor. Most stories such as “The Thing in the Crypt” (Conan, 1967) were short monster stories that would later characterize the type of story in the Marvel comic book, Conan the Barbarian. Not at all like the intrigues and grand-scale adventures generally found in Howard’s Conan stories but sword-and-sorcery of a different, almost bite-sized, sort.

This period was a good one for Lin Carter if not, ultimately, for his reputation. The Conan boom of the late 1960s opened up new markets for him. Carter had set forth on a career of writing heroic fantasy before heroic fantasy was in fashion. The boom in the wake of the success of the Lancer Conan paperbacks brought L. Sprague de Camp back to writing fantasy fiction after ten years hiatus concentrating on non-fiction at that time. Writers whose careers reached back to the end years of the pulp era including Gardner Fox and John Jakes were now suddenly writing sword-and-sorcery to meet the unprecedented demand. And Carter’s Lemuria was part of the new heroic fantasy itinerary. Paperback Library became the publisher of the next three Thongor novels in 1967 and 1968, which had the added bonus of having Frank Frazetta paint two of the covers and Jeff Jones the third. These novels continued in the pattern already set with the first two Thongor novels and did not radically depart from what Carter, in the thrall of Burroughs and to a lesser extent Howard, had already established.

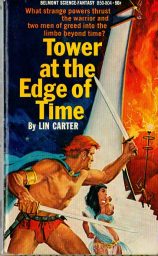

Tower at the Edge of Time (Belmont Books, January 1969) mixed space opera and sword-and-sorcery even more than had The Star Magicians. It had the same background universe as The Star Magicians but was set hundreds of years later, with one Thane of the Two Swords as its hero. He is described thus:

Tower at the Edge of Time (Belmont Books, January 1969) mixed space opera and sword-and-sorcery even more than had The Star Magicians. It had the same background universe as The Star Magicians but was set hundreds of years later, with one Thane of the Two Swords as its hero. He is described thus:

“Tall he was, and grim of face; naked, but for a loin cloth of scarlet silk, a leathern harness of belted straps set with square studs of bronze, and a vast blue cloak that swung from broad, bare shoulders. His hair poured over his brawny shoulders like a crimson flood. It was red: not rust or bronze or gold, but- red– an arterial crimson metallic in luster and startling to behold. From this you might have known him for a son of Zha the Jungle Planet, for only the Zhayana have such hair.”

Lin Carter had a predilection for jungle lands and worlds, to the extent that it is somewhat startling to come across the snowy, sub-Beowulfian setting of his Thongor short story “Black Hawk of Valkarth.” He did not incorporate the wide array of climates, lands, and cultures in his fiction the way Robert E. Howard did. Howard liked to “telescope history” using cultures from all sorts of historical periods. Carter’s fictional worlds generally had the same culture and language with little variation. This habit reinforces the idea that Edgar Rice Burroughs was the overwhelming influence on Lin Carter’s writing style as Burroughs generally did the same thing. A reading of Tower at the Edge of Time fosters a sense of déjà vu after reading The Flame of Iridar and The Star Magicians. Thane has the secret of the Time Wizards treasure. The Time Wizards were creatures of pure thought “who had come into the galaxy a billion years before the advent of Man.” Seven years before, Thane was a member of a band of space pirates that raided the world of Mnom where the Time Priests tended the crystal talisman. Thane broke the crystal and a “fog of light” entered him giving him the ability to sense future events. Prince Chan captures Thane and forces him to open the Web of Time, which flung Thane, Prince Chan, and their companions to the end of time. Vast treasures are revealed within the tower and Prince Chan and his dwarf sorcerer kill each other at that moment of discovery. The treasure disappears, having been an illusion created by the Time Wizards who reveal the real treasure is love, comradeship, honesty, tolerance, friendship, and respect. Thane returns to his own time with a new love, Illara, as his treasure. In this book, there is no direct divine intervention against the villains, who conveniently destroy each other at the end of the novel. Tower at the Edge of Time had no less than five editions from 1968-1982, making it Carter’s most reprinted book.

Up to this point, Lin Carter had written in a straightforward prose style devoid of many affectations. He admired E. R. Eddison, James Branch Cabell, and Lord Dunsany and those influences did begin to creep in. Carter wrote The Giant of World’s End (Belmont Book, February 1969) in a different prose style from his previous novels. Gone is the Burroughsian nomenclature; names such as the Dunsanian sounding Yaahthab Shanderzoth are substituted. Carter got the idea of the far future tale from Clark Ashton Smith, Jack Vance, and A. E. Van Vogt and made use of it with his continent of Gondwane 700 million years in the future. Ganelon Silvermane is the hero of this book, an artificially created “construct” from the genetic vats of the now departed Time Gods. The Time Gods created Ganelon to save the Earth from the falling Moon. He searches out Zelobion the Magician to accompany him on his mission. Arzeela the Amazon joins the two of them along the way. She falls in love with Ganelon who cannot love, being an emotionless Construct. Rejected, Arzeela sacrifices herself at the end of the novel in a machine relic left behind by the Technological Empire. The machine destroys anyone who uses it, as the body is consumed in the “field effect.” Ganelon is left to wander Gondwane to find the meaning of love. The book is memorable for the outcome. Again, you have the Carter triumvirate of warrior, wizard, and female romantic interest.

Carter’s next novel was probably the pinnacle of achievement in his career, The Lost World of Time (Signet Books, November 1969). Signet at that time published some sword-and-sorcery novels wherein editor David Hartwell was able to get more out of the writer than cynical hackwork. John  Jakes (The Last Magician) and Ben Haas (Exile’s Quest), who wrote as Richard Meade, are examples of writers who produced some of their best fantasy fiction for Signet at this time. The books typically had water color paintings as cover art that distinguished them from the Frank Frazetta and Jeff Jones look predominating at that time. Carter liked “imaginary worlds” fantasy by E. R. Eddison, James Branch Cabell, and Lord Dunsany, and in The Lost World of Time he tried his hand, but in his pulp derived style. Reach does not exceed grasp, which makes for readability.

Jakes (The Last Magician) and Ben Haas (Exile’s Quest), who wrote as Richard Meade, are examples of writers who produced some of their best fantasy fiction for Signet at this time. The books typically had water color paintings as cover art that distinguished them from the Frank Frazetta and Jeff Jones look predominating at that time. Carter liked “imaginary worlds” fantasy by E. R. Eddison, James Branch Cabell, and Lord Dunsany, and in The Lost World of Time he tried his hand, but in his pulp derived style. Reach does not exceed grasp, which makes for readability.

The Lost World of Time is the planet Zarkandu in ages past before its destruction, the debris from which becomes the Asteroid Belt found between Mars and Jupiter. Zarkandu’s Sacred Empire teeters on the edge of disaster from decadence within and invasion without. Shadrazar the Warlord, Son and Avatar of the Black God, has united three different barbarian hordes and assaults the declining Sacred Empire. Princess Alara seeks a hero who is the living avatar of the Divine Hero according to prophecy. A wandering barbarian, Sargon the Lion, meets the description of the prophecy and is enlisted to carry a mighty war hammer of legend. Shadrazar uses sorcery to abduct the princess but Sargon pursues and rescues her in the stronghold of the enemy. A mighty battle at a mountain pass where Sargon uses the hammer to bring down a portion of a mountain down on the invading horde finishes out the novel. Carter repeatedly used hordes of villains in his fiction. He had been an infantryman in the U.S. Army in the Korean War. Combat against charging human waves of Communist Chinese troops in Korea may have made an impression on him that resurfaced in many of his novels. Though Sargon has a legendary weapon that is wielded to devastating effect in combat, there is no divine intervention or deus ex machina device. A portion of the horde is destroyed but Shadrazar is not completely defeated, only sealed off from the empire and still a potential threat. The novel was not merely a series of strung together incidents that have no bearing to the plot but was a true linear story. Nothing was superfluous. This was the novel Lin Carter was capable of writing when he truly applied himself. Either David Hartwell or an assistant editor was able to extract out of Carter or push him to write to the level he was capable. He would never equal this achievement again.

The advent of original sword-and-sorcery anthologies gave Lin Carter an opportunity to write some shorter stories about Thongor. He went back to events before The Wizard of Lemuria to write two stories with a markedly reduced Edgar Rice Burroughs influence for anthologies edited by Hans Stefan Santesson. “Thieves of Zangabal” (The Mighty Barbarians, Lancer Books 1969) owes its plot to Robert E. Howard’s “Rogues in the House.” A priest hires Thongor to steal the magic mirror of Athmar Phong, a mighty sorcerer. Thongor battles a demon and manages to kill Athmar Phong, rescuing his new friend Ald Turmis in the process. “Keeper of the Emerald Flame” (The Mighty Swordsmen, Lancer Books 1970) had Carter recycling some elements used originally in “The Thing in the Crypt.” Thongor and his bandits find a lost city in the jungles of Lemuria. His men are killed one by one at night and he discovers an animated mummy of a once powerful wizard performing the crime. These stories are set on a small scale in comparison to the novels for Thongor. Carter had a tendency to overwrite and draw out his shorter Thongor stories during the final climax. Both of these stories could have been cut and not lost anything in the telling. Less would have been more in this situation.

Carter introduced Kellory the Warlock in “Vault of Silence” for Sword Against Tomorrow (Signet Books, 1970). Kellory, last survivor of the Black Wolf Clan, is a sorcerer bent on vengeance against the nomadic Thungoda Horde. Some have speculated that Michael Moorcock’s Elric may have been the inspiration for Kellory, but the Carter character was more reminiscent of John Brunner’s Traveler in Black than Moorcock’s self-destructive albino.

Carter returned to nomads in The Quest of Kadji, and used the plot of Harold Lamb’s Kirdy. The Kozanga nomads are similar to the Cossacks of this world and defenders of the Empire and its emperor. Due to skullduggery, the Dragon Emperor of golden Khor names the Kozanga nomads outlaw and sends foreign mercenaries to destroy the nomads. Kadji, last survivor of the nomads, bears the magic ax of Thom-Ra and embarks on a quest to kill the pretender who has seized the emperor’s throne during the course of the novel.

The Black Star (Dell Books, May 1973) was the last of the novels in the Lin Carter style. According to Robert M. Price in Lin Carter: A Look Behind His Imaginary Worlds, Carter wrote this novel around 1970, but it was not published until a few years later. Carter had previously avoided Atlantis out of deference to Cutliffe-Hyne, Clark Ashton Smith, and Howard, but now he forsook Lemuria for the more famous foundered continent. He used W. Scott-Elliott’s theosophical writings on Atlantis for plot elements in this story. The novel begins with the overthrow of the Emperor of Atlantis and the capture of the capital city by the Demon King and his legions. The warrior Diodric escapes with Lady Niane in a Lemurian airboat with a powerful symbol, the Black Star. The Black Star is a gem that is the key to holding power in Atlantis; no one can rule without possessing the gem. After the Lemurian sorcerer Nephog Thoon rescues Diodric and Niane from Troglodytes, the Demon King brings down the airboat by sorcery, allowing his soldiers to catch up in order to seize the Black Star. There is a battle with the Demon King’s soldiers, Diodric losing an arm to a poison arrow, and the Black Star is lost but not captured by the Demon King’s minions. The travelers find refuge in the unconquered western portion of Atlantis. Carter intended a sequel to be called The White Throne, but the project had to be scrapped after a chapter or two. The sword-and-sorcery boom of the late 1960s went bust by 1971 as publishers were bought out and changed hands. Dell Books may have felt there was no audience for The White Throne. Perhaps low sales for The Black Star justified the decision. This was unfortunate as The Black Star was one of Carter’s better novels, and his subsequent work would fall off dramatically.

The Black Star (Dell Books, May 1973) was the last of the novels in the Lin Carter style. According to Robert M. Price in Lin Carter: A Look Behind His Imaginary Worlds, Carter wrote this novel around 1970, but it was not published until a few years later. Carter had previously avoided Atlantis out of deference to Cutliffe-Hyne, Clark Ashton Smith, and Howard, but now he forsook Lemuria for the more famous foundered continent. He used W. Scott-Elliott’s theosophical writings on Atlantis for plot elements in this story. The novel begins with the overthrow of the Emperor of Atlantis and the capture of the capital city by the Demon King and his legions. The warrior Diodric escapes with Lady Niane in a Lemurian airboat with a powerful symbol, the Black Star. The Black Star is a gem that is the key to holding power in Atlantis; no one can rule without possessing the gem. After the Lemurian sorcerer Nephog Thoon rescues Diodric and Niane from Troglodytes, the Demon King brings down the airboat by sorcery, allowing his soldiers to catch up in order to seize the Black Star. There is a battle with the Demon King’s soldiers, Diodric losing an arm to a poison arrow, and the Black Star is lost but not captured by the Demon King’s minions. The travelers find refuge in the unconquered western portion of Atlantis. Carter intended a sequel to be called The White Throne, but the project had to be scrapped after a chapter or two. The sword-and-sorcery boom of the late 1960s went bust by 1971 as publishers were bought out and changed hands. Dell Books may have felt there was no audience for The White Throne. Perhaps low sales for The Black Star justified the decision. This was unfortunate as The Black Star was one of Carter’s better novels, and his subsequent work would fall off dramatically.

Carter’s period of relative originality was now over. He experimented with imitating Lord Dunsany in his Simrana stories and in his excerpts from what was supposed to be the massive Khymyrium, which was never finished or even sustainedly embarked upon, he ventured into the territory of E. R. Eddison. He never stayed long in the realm of either of those writers. Carter backslid into producing close imitations of Edgar Rice Burroughs sword-and-planet fiction with the Callisto books for Dell and the Green Star series for D.A.W. These publishers may have wanted Burroughsian fiction to compete against Ace and Ballantine, who both published Burroughs at that time. Carter had a steady—perhaps too steady— market with editor Donald Wollheim who had left Ace and founded D.A.W. Books. Wollheim always published far more Burroughsian sword-and-planet over Howardian sword-and-sorcery, first at Ace Books and then at D.A.W. Edgar Rice Burroughs may have had such an overwhelming formative influence on Carter that he was incapable of breaking free.

Carter went back to write novels about Ganelon Silvermane and events that occurred before The Giant of World’s End during the middle 1970s. Unfortunately, Carter indulged his taste for supposedly humorous fantasy that owed a great deal to L. Frank Baum’s Oz books. Baum’s Oz books are filled with gentle political and social satire, Carter on the other hand wrote heavy handed burlesque in the World’s End series that make for painful reading. He also wrote four more Thongor stories, three of them published in Fantastic Stories then edited by his friend, Ted White. Two Conan pastiche stories returned to their Thongorian roots during this period. They are the same sort of monster stories as the two earlier Thongor stories from the Han Stefan Santesson anthologies. Better are stories about wandering cave men working their way up to barbarism in “People of the Dragon” and “The Pillars of Hell” that appeared in Fantastic Stories in the middle 1970s. By this time, Fantastic Stories was publishing fiction by Keith Taylor and Karl Edward Wagner and the short Thongor stories were embarrassingly simplistic in comparison to the more sophisticated stories and plots by subsequent writers of sword-and-sorcery. In Carter’s shorter fiction, the Burroughs influence was less pronounced than with his novels at that time. The Thongor novels were reprinted in the late 1970s during the second sword-and-sorcery boom. According to Robert M. Price, Carter drew up plans for a long parade of new Lemurian novels starring Thongor or his Burroughsian whelp Thar, but the novels never materialized. The 1980s saw fewer books by Carter and all were humorous fantasy or Doc Savage homages with the exception of Down To a Sunless Sea (D.A.W. Books, 1984), the last of his attempts to prospect in the outback of a Leigh Brackett-style Mars. Carter may have simply reached creative exhaustion, and in his last years he retreated to semi-prozines and similar small press venues.

So are we justified in speaking of a Lin Carter style at all? He attempted to bridge the gap between Burroughsian sword-and-planet and Howardian sword-and-sorcery by combining barbarian swordsmen with pseudo-science with a dash of Lovecraftian supernatural menace thrown in. Write a short novel in a pulp style derived from Edgar Rice Burroughs with some Dunsanian word flourishes and that was Carter’s style. If the fiction was a short story or novelette, it was a monster story that would not be out of place in a comic book. Carter had a style of a sort in the first portion of his career, but most of the later books were driven by contracts (courtesy of Wollheim and others) rather than content. Fittingly, one of his collections was entitled Lost Worlds and one of his novels was entitled Lost World of Time, for among the worlds he lost was that in which he might have developed his own unmistakable identity as a genre writer.

[1] Archie Mercer, “Scroll, with Salt,” Amra V2, #36 (Chicago: Terminus, Owlswick, & Ft Mudge Electrick St Railway Gazette): 17

[2] Harry Harrison, “Scroll, Chopped Vigorously,” Amra V2, #36 (Chicago: Terminus, Owlswick, & Ft Mudge Electrick St Railway Gazette): 18

[3] ibid: 19

While I have a few quibbles, this is the best piece on Lin Carter the AUTHOR that I’ve ever read.

For the best overview of Carter’s massive impact on the fantasy genre as an EDITOR (and scholar), then this is the book to read:

http://www.palgrave.com/us/book/9781137518088

Excellent. Thank you! I was a big fan of Lin Carter back in the day and have a great number of his paperbacks.

My only major experience with his writing was Sagas of Conan, where he contributed to many of the stories. Let’s just say that I didn’t actively pursue works by any of the involved authors after that. Fascinating read nevertheless.

Great essay.

Lin Carter always rated higher as an editor than as an author and with good reason. He was a sloppy writer Example: In Thongor in the City of Magicians the evil wizard denies the existence of the soul but a couple of pages layer he dooms Thongor’s soul to eternal slavery in chaos. And you are right He got worse with the years.

C

I agree with most of what is represented in this article. Another good Carter novel was THE THIEF OF THOTH (An Ace double with Harlan Ellison’s DOOMSMAN). Carter could do humour very well.

Read your Lin Carter Style essay with great interest and appreciation. You are perhaps the only source I can find who talks about Carter’s “People of the Dragon” short stories. I know Carter conceived it as a series, and I know “People of the Dragon” appeared in the February 1976 issue of Fantastic and “The Pillars of Hell” in the December 1977 issue. Were there only two Dragon tribe tales? Did he continue with this saga? If so, what were the other titles in the series?