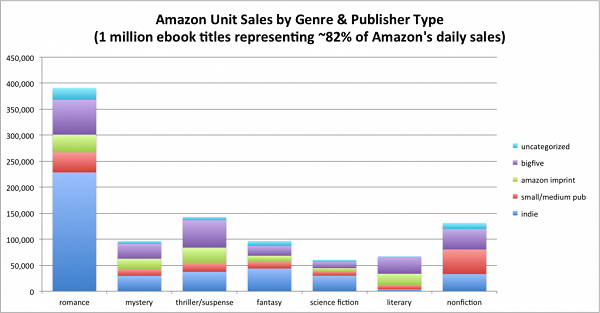

Author Earnings recently released their statistics for 2016 book sales. As industry hands and book reading fans poured over the results, one of the more interesting facts is that science fiction sold the least of all the major categories. This is not a surprise to those who have been following the shrinking sales of the Big Five in this category, although it is still unwelcome. Unfortunately, the worst is yet to come.

A survey of modern science fiction shows a repeated pattern of extinction events. In the 1950s, the pulps died. At the end of the Crazy Years of the 1970s, magazines died as the primary medium of science fiction and backlists withered away. The 1990s and early 2000s killed off the midlist writer. And, as the same old song plays of magazine sales drying up, rumors of publisher woes, and publisher wisdom telling authors that science fiction cannot sell, we stand on the verge of the next great crash for the genre. That this crash is happening in the 2020s and not in the 2010s is due to the 1990s’ publishing woes lasting into the 2000s, pushing back the date of the upcoming crash.

Each crash came about at the intersection of a change in the publishing industry and soft sales. The pulps failed as digest and women’s magazines grew profitable. The novel grew ascendant in the 1970s, and changes in tax laws made backlists a tax burden. Reliance on Bookscan and other sales tools sent publishers looking for blockbuster bestsellers instead of growing their midlist writers. And, in the current day, ebooks are proving just as disruptive, with more than 80% of all 2016 science fiction sales coming from ebooks according to Author Earnings. But while writers cannot control the changes in the industry, they can at least avoid the mistake that repeatedly led to soft sales:

Realism.

Or to be more proper, literary realism. This is not the same thing as factual accuracy, as even the hardest SF technothriller falls outside the realm of literary realism. Rather, the realism described here is the literary realism as that ushered in by William Dean Howells, who

…proscribed writing about “interesting” characters–such as famous historical figures or creatures of myth. He decried exotic settings–places such as Rome or Pompeii, and he denounced tales that told of uncommon events. He praised stories that dealt with the everyday, where “nobody murders or debauches anybody else; there is no arson or pillage of any sort; there is no ghost, or a ravening beast, or a hair-breadth escape, or a shipwreck, or a monster of self-sacrifice, or a lady five thousand years old in the course of the whole story.” He denounced tales with sexual innuendo. He said that instead he wanted to publish stories about the plight of the “common man,” just living an ordinary existence.

This avoidance of the fantastic, the exotic, and the sensational is directly opposed to the spirit of science fiction, to the extension of an idea into a speculation of the unknown. Rather than extraordinary people doing extraordinary things, or even ordinary people rising to the occasion in extraordinary times, literary realism is fascinated with ordinary people doing mundane things. In the 150 years since Howells proposed it, literary realism became the primary philosophy of literary fiction, and every attempt by science fiction to become more literary has also included a fascination with his realism. And this realism tanks sales of fantastic literature. For example, when Campbelline writer Babette Rosmund took over as editor of The Shadow Magazine in 1946, she introduced changes to the stories that fell in line with the realism en vogue with the new generation of pulp editors:

While the writing in this new pulp was palatable, the major problem was that The Shadow no longer existed in it. Instead, Lamont Cranston became the hero, solving mysteries with the police. All hints of a secret identity were ignored. The Shadow lost all his superhuman qualities. His guns remained holstered, his laugh rarely pealed across the pages. Removed were the cast of supporting characters and the villains. The agents and the gadgets. The Shadow’s laugh and his blazing 45’s.

Under her direction away from the fantastic and exotic elements that were essential to making the Shadow, “the magazine fell back to bimonthly and then to quarterly as sales continued to fall.” A similar drop in sales also plagued Doc Savage under Rosmund’s leadership.

This is the reason that science fiction as a publishing category nearly died off in the 1990s. Things have improved a lot in this century, but that doesn’t help the perception that the writers who toiled in the successful, but less accepted, subgenres didn’t exist at all.

I mention the literary part of the genre because it held its strongest sway in the short fiction categories. It’s easier to maintain a magazine with literary pretentions than it is to maintain a book line with the same attitudes. A lot of sf book lines died in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some magazines, including the one that I used to edit, lost a vast amount of readership when those literary attitudes I just mentioned took over at the turn of this century.

This coincided with the rise of slipstream fiction. The current plunge coincides with the uptick of realism brought in by intersectional politics, which seeks to impose a narrower grade of realism on the genre, as instead of a common man, these writers explore the plights of specific and numerically smaller minorities. What might start as the examination of the plight of the common man gets pushed aside for the common woman who gets pushed aside for the common Hispanic woman who in turn gets pushed aside for an even smaller minority subset. And the sales continue to fall, and publishing continues to writhe with the changes caused by ebooks. For a struggling genre, the worst is yet to come.

However, there is a shelter for authors in the upcoming storm, one that has time and again proven reliable for authors: adventure stories. This is not setting specific. Science fiction’s hits are spread throughout the entire spectrum of hard and soft science fiction, from the technological fantasies of 20,000 Leauges Under the Sea, Jurassic Park and The Martian, to the scientific-marvelous speculations of War of the Worlds and Fantastic Voyage, to the planetary romances of Star Wars, Dune, and Halo. Each one is a tale of adventure and extraordinary acts, at odds with literary realism’s ideas of the mundane, and each has found a home in popular culture as a result.

Adventure builds audiences. Doc Savage and The Shadow both rebounded after Rosmund departed Street & Smith, regaining their audience with the return to their fantastic adventures. Although both were later cancelled in the sweeping cut that murdered every Street % Smith pulp with the sole exception of Campbell’s Astoudning, Will Murrary points out that the reason was not tied to flagging sales:

Oddly, Doc Savage was not canceled because of lagging sales. It was, by all accounts, healthy. But Street & Smith was growing fat and respectable with its women’s magazines like Madmoiselle and decided that its pulps and comic books were not what the company wanted to be all about. It was a classic wrong-headed business move.

Murray, Will. Writings in Bronze (p. 213). Altus Press. Kindle Edition.

Also, at a time where audiences were supposedly clamoring for increased realism, Amazing, with its implausible and outlandish Shaver Mystery underground adventure, set sales records that no science fiction magazine has yet to break. The further adventures of Star Wars and Star Trek popularized media tie-in novels, frequently gracing best-seller’s lists and paying for the rest of the genre. More recently, Kristine Kathryn Rusch describes how some magazines thrived in the lean times of the 1990s:

On the other hand, some of the sf magazines grew in circulation. For example, Asimov’s Science Fiction grew in overall circulation after Sheila Williams became editor. She got rid of a lot of the slipstream fiction (the stuff you couldn’t tell from realistic fiction) and purchased a lot of space opera and adventure fiction.

Since adventure sells when realism does not, the way to survive the upcoming crash is simple. Embrace the fantastic and the exotic. Embrace adventure.

Avoid literary realism.

Serious question: What specifically makes it an “adventure” rather than a tale of extraordinary acts?

I’m not nitpicking or engaging over semantics, it’s just that I’ve been following the genre wars and the color coding wars (blue vs red vs pink vs pink slime vs purple, oh my) and “SF adventure” as opposed to just SF has come up. Same with “fantasy adventure.”

-

An adventure typically involves a voyage into the unknown. I would define War of the Worlds as a tale of extraordinary acts and The Time Machine as an adventure, but not necessarily a tale of extraordinary acts (the time traveler doesn’t do much).

For this argument, I am not treating adventure, a tale of the exotic, or a tale of the extraordinary as different. All three run counter to the ideals of literary realism.

I have argued for years that there was need for an adventure science fiction magazine. Something along the lines of the Clayton era Astounding Stories (of Super Science), Planet Stories, Science Fiction Adventures. The last attempt was Isaac Asimov’s SF Adventure Magazine which did not have a chance being edited by George Schithers and Darrell Schweitzer.

The problem with literary realism is that it is boring, and the one rule that a writer of fiction cannot violate ever under any circumstances for any reason is:

Don’t be boring.

I have serious problem with that graph. Actually 2. 1 if speculative fiction embracing both science fiction and fantasy is the real genre then they should be combined in our graphs. 2 as far as I can tell amazon uses the classics definition of literature for their categorization. Therfore sci-fi classics such as brave new world, 1984, and three body problem are included under literature. And so is required reading books like a tale of two cities or middle march.

-

Exactly. “Literature” is an umbrella genre. It can be “Literature” and SF. “Literature” and Romance. “Literature” and Fantasy. Treating “Literature” as if it’s NOT an umbrella genre only muddies the water. Same with the other umbrella: Young Adult.

-

Young adult isn’t even an umbrella, it’s a house.

-

Down with Literary Realism!

People want to escape. Many of them have just about as much realism as they can handle in real life. Unemployment, illness, heartbreak, debt…the list goes on.

Give them a chance to escape that, if only for a little while, and they’ll follow you.

Down with realism!

All Hail Romance, Adventure and Wonder!

-

Well said!

I think that part of what may be happening as well is genres that had been previously limited to metaphysical realism are opening up in response to self-publishing.

That is to say that twenty years ago you didn’t find werewolves and vampires in Romance–of a book contained fantastic elements it had to be marketed as SF/F (The Anita Blake novels, for example.)

Horror, which I see doesn’t even have a listing on that chart (I guess it’s under “Thriller”?) was allowed some contrafactual elements, but even that was limited. (Clive Barker, for example, straddled the line and some works were considered Horror, some SF, although the elements were very similar.)

SF/F was like the only liquor store in an otherwise dry county–people didn’t particularly want to shop there, but it was the only place to get booze.

These days there are a dozen markets that sell the fantastic–so why go to something called SF/F when you can get the fantastic elsewhere, as well as doing your other shopping for love and fear and all the rest.

I suspect that much of what you see hear as a sales problem is a consequence of relabeling. If you took all of the “Paranormal Romance” and stuck it back into SF this graph would be very different.

-

“Horror, which I see doesn’t even have a listing on that chart (I guess it’s under “Thriller”?)”

Yes, as a separate “genre” it’s dead. If you want to sell, relabel as Thriller or Suspense.

“I suspect that much of what you see hear as a sales problem is a consequence of relabeling. If you took all of the “Paranormal Romance” and stuck it back into SF this graph would be very different.”

Agreed. It’s speculative fiction just like SF&F. And with all the blurring of genre boundaries as well as mixing of SF & F elements into the same cauldron, it makes more sense to bundle them all together. Hey, a melting pot!

-

Wow. Horror is dead? I wonder how that happened. Back in the age of the dinosaurs when I used to browse local bookstores it was a big section–at least as big as Fantasy.

-

I’m not sure that it is fair to label it as dead, as you can still see books tagged as horror reaching overall top ten on Kindle or print stores. And there’s a prodigious amount of it being released, though it shifted from novels to short story collections.

But the day of paperback horrors being all the rage are long gone.

-

-

On this I vehemently disagree. Paranormal romance is romance. Just like pirate romance and regency romance are not historical fiction.

-

It has something to offer its readers that is more than just romance–otherwise it wouldn’t be as big as it is. It may not be what you want from the fantastic, but it appeals to a market.

-

-

I get reality for free every day. Why would pay for that crap in my entertainment? And I sure as hell don’t put it in my own novels!