The #pulprevolution is in full swing, and new cells of activity are popping up all over the place. People are writing, people are organizing, people are producing things and getting them out into the wild.

The #pulprevolution is in full swing, and new cells of activity are popping up all over the place. People are writing, people are organizing, people are producing things and getting them out into the wild.

It’s amazing to watch it happen, but even more amazing to participate in it, and I really hope some of the people stepping up right now have the right stuff to keep it going so that I can see where this goes in a year or two.

But let’s take a step back and ask: what is it that makes great stories great?

Now, full disclosure: I’m on that Pulp Revolution train. But I don’t for one minute think the pulp aesthetic is the be-all and end-all of great stories. I think it’s possible to write great stories in any “aesthetic” – whether it be pulp, slick, epic, horror or something else. Obviously, what floats a given reader’s boat is going to vary, and if you ask 10 readers for their opinion of what is best in fiction you’ll probably get at least 11 answers.

But there does seem to be a sweet spot that more or less defines what gets recognition and enthusiasm among the fans of any aesthetic.

Where is it?

Over the years, I have dug through classics old and new, I have read new work of various kinds, and I have done line editing and beta-reading for a number of up and coming authors. I have seen good work, atrocious work, and work that made me grind my teeth with frustration because the writing skill was clearly there, but the story was dead on the page. My perspective is very much that of a reader, I suppose, but I believe I have identified (at least in philosophical terms) where that sweet spot hides:

I think it lies in the interface between the characters and the situation.

No story can survive without compelling characters – without the characters, and some reason for the reader to be invested in them, there’s no motive to read further and find out what happens to them.

But likewise, no story can survive without a compelling situation for the characters to interact with.

The intersection between the characters and the situation is where the story lives.

The more successfully the writer infuses the characters and the situation with compelling characteristics the more deeply engaged the reader is going to be.

I don’t think it matters what kind of aesthetic the writer is aiming for: This is how we as readers recognise great stories, and it’s the stories that combine the most compelling characters and the most compelling situations that stand the test of time.

What the aesthetic does is inform the writer’s decisions as to just how to go about making characters and situations compelling. It’s a recipe; the writer’s imagination supplies the ingredients, but without the recipe there will be no story.

If this all seems obvious, that’s because it is, but it’s a fact of story-telling that is too often forgotten by writers. Particularly in SFF, there’s a temptation to lose sight of the big picture and go racing off into the weeds of “world creation”, “setting”, and “character background”.

The truth is, it’s not setting that’s the key, not really.

It’s the situation, and the characters as they are now as they interact with the situation that drive the story.

When you look at the best writing, it’s clear that setting/world and character background emerge from this.

So for those readers here who are also aspiring authors: don’t even try to be Tolkien – the bad news is that not only are you not in his class, but the 12 year process that went into his production of Lord of the Rings is counterproductive in two ways:

1. It bogs you down in the weeds, it increases the danger that the story you’re writing won’t be as awesome as it is in your head, and it really increases the danger you’ll fall into the trap of pointless infodumps.

Focus on the interface, focus on the action, and you’ll be on to a winner.

2. Allow me to raise my voice so that those of you in the back can hear: IT TAKES TOO LONG!

Don’t waste your time fiddling around with these details when they can emerge in the story. Focus on the character now. Focus on the situation – then set the machine in motion and make it happen.

So now for the homework: get out there and write!

For the glory of the revolution!

The shadow of Tolkien is a long one.

For the opposite of Tolkien, look at manga artist Akira Toriyama. His magnum opus Dragon Ball — which, in the manga publications includes what is known to anime fans as Dragonball Z — did not start with notebooks upon notebooks of detailed world-building and finely crafted character background. It started with characters and a story, and it was entirely written on the fly, with little to no pre-planning.

Toriyama’s success is a testimony to Winkless’s words.

Give your readers two things: A reason to hope that things will turn out ok for your character, and a reason to fear that they won’t.

Glenn Cook still hasn’t made a map, and doesn’t intend to, for his _Black Company_ novels. And that, I think, is a good thing.

-

Yeah, that map thing really screwed up Robert E. Howard. If only he hadn’t done three maps of the Hyborian Age — that we know of — then maybe he could’ve been truly creative like Cook and Leiber. Too bad ol’ Two-Gun crippled himself that way. If only he’d known!

I think mystery also fits in there somewhere. Even with a good situation and a good character, if there is nothing I want to learn about the universe the story is in, I lose interest immediately.

Series kill themselves right after they explain all of their mysteries.

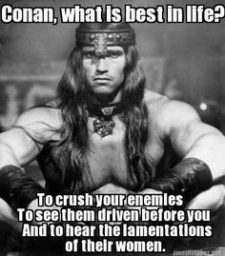

To crush the dreams of your protagonist.

To see him driven to obtain them anyway.

And to fulfill surprisingly the expectation of the reader.

“Do you always outline your stories?”

“Absolutely.” He [Robert E. Howard] paused, thinking. “Oh, once in a while, I put a sheet of paper in my typewriter and start out and get where I’m going with no outline at all. But the way I explain such things is that it’s either been gestating in my mind, or I have lived it or knew about it in some other life. I don’t want to leave the wrong impression. Most of the yarns I write are planned very carefully, and they’re complete with a detailed outline.”

From ONE WHO WALKED ALONE –- by Novlalyne Price Ellis

It’s not a question of planning and outlining, nor a matter of having clear ideas about the space in which the story occurs. It’s about focus. Howard drew maps and assembled notes on the Hyborean age – but it’s also clear that each iteration was incorporating facts that emerged in stories he had written or was writing. The danger is in getting stuck in a vicious cycle of over-emphasis on irrelevant details that leads to ponderous info-dumps and de-emphasis of the story itself. Planning is obviously important. Pulling details together into a coherent whole is critical for an integrated, extended story. But finding the balance between plans and action is the key. And I think that balance lies in planning only as much as is required for the current story, then incorporating what else emerges into future tales that connect. The writer isn’t an omniscient native of the territory, but a trailblazer going forward to scout the terrain before coming back to guide the reader through the best route to the next landmark.