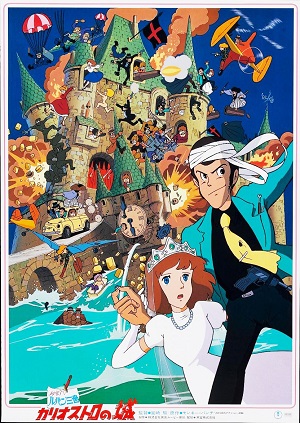

50 YEARS OF LUPIN III: The Castle of Cagliostro

Sunday , 13, August 2017 Art, Comics, Movies 7 Comments

Heroism goes along with my job.–Lupin III

After stealing bags of cash from a Monaco casino, Lupin and Jigen dump out their entire haul, recognizing the money as legendary Gothic counterfeits. Resolving to find the plates for their next caper, the thieves slip into the small Italian principality of Cagliostro. Their search is interrupted when a car full of mafioso chase down a runaway bride, Princess Clarisse of Cagliostro. Both the counterfeits and the intrigue around Clarisse’s wedding can be traced to the Count of Cagliostro. To save the girl–and the loot–Lupin forms an alliance with his greatest rival, Inspector Zenigata of the ICPO.

Rereleased in theaters as part of the 50th Anniversary celebration of the Lupin III franchise, 1979’s Castle of Cagliostro is the central Lupin III adventure, setting the tone and standard for the franchise for the nearly 40 years since its release. And as the Lupin franchise has grown more self-referential, adventures such as 2008’s Green vs. Red and 2015’s Blue Jacket television series have leaned heavily on Castle of Cagliostro for their soundtrack, design, settings, and even plot. Yet Castle of Caglisotro might be best known for its screenwriter and director, the legendary Hayao Miyazaki, creator of Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Even then, it is considered an afterthought to the brilliant animator’s oeuvre, because it is an adaptation instead of an original work. (For an example from the CH Blog, see Anthony’s otherwise glowing review of Castle of Cagliostro.) Such reviews, usually by critics unfamiliar with Lupin, miss a chance to fully appreciate the genius of Miyazaki. For before his involvement in 1971, the Lupin franchise was sinking under the weight of irredeemable and brutal characters. Afterwards, he handed over a winning formula and an appreciative audience that has been copied by animators all over the world.

Miyazaki’s changes should be familiar to long time readers of this retrospective. The most important of these was to give Lupin a heroic goal to accomplish alongside his selfish goal of thievery. Many of the remaining changes followed after to make the sociopathic thief more palatable as a hero. Gone are his ruthlessness, pleasure in the pain and death of others, and delight in violence and rapine. After all, what hero would, after rescuing the heroine, immediately despoil her of treasure and virtue? Monkey Punch’s Lupin would have, but then that version of Lupin was an arch-villain, and no one to cheer for. Thus Lupin was defanged, made harmless through humor. He wasn’t even allowed to dispatch Count Cagliostro, who had to perish from his own machinations instead of Lupin’s new Walther P38. Lupin also picked up a love for gadgetry, which, in true Miyazaki fashion, is grounded in actual techniques instead of hand-waved like in future films. Other characters go under the editorial knife. Glamour girl and walking double entendre Fujiko Mine has her sensuality very nearly turned off. Meanwhile, Jigen becomes Lupin’s ever present right hand man, replacing the networks of henchmen reporting to Lupin. While the changes might be severe violence to the spirit of the manga, they turned a failing TV show about to be cancelled at its third episode into an international franchise. And the appearance of the franchise was also codified by Miyazaki. Lupin’s taste for Fiat cars and his signature sidearm, the Walther P38, first appear in Castle of Cagliostro. And it set the tone for an almost twenty year losing streak where Lupin and his gang always found the treasure, but could never keep it.

For all the changes made, Miyazki retained several features from the manga. Whenever Clarisse is absent, Lupin maintains his lechery, although it is considerably toned down from the manga’s penchant for impending rape. While the bonds between Lupin, Jigen, and Goemon are stronger, they are sstill treated as three thieves who occasionally work together and come and go as they please. Lupin’s delight in theatrics and misdirection survive unscathed, with Clarisse’s wedding serving as a trademark display. And, finally, the action scenes invoke more than a passing nod to Looney Tunes and Tom & Jerry director Chuck Jones, an inspiration for Monkey Punch’s original manga.

Also unremarked by many critics is that Miyazaki made Castle of Cagliostro among the most literary of Lupin III adventures, following artist Monkey Punch in mining the adventures of Arsène Lupin, by Maurice Leblanc. Elements of “The Arrest of Arsène Lupin” appear, as both Arsène Lupin and Lupin III both sneer at counterfeits. Lupin III’s affection for Clarisse is reminiscent of Arsène’s for Nelly. Like Arsène, Lupin III had an encounter with the Cagliostro family early on in his career, only to return for a showdown towards the end. And Count Cagliostro even namedrops the elder Lupin in the film. But where Lupin the First squared off against a wily Countess Cagliostro who became his greatest rival, Miyazaki reached further into history to the original Count Cagliostro, a conman and occultist that plagued France in the late 1700s. Thus the modern Cagliostros are also master forgers, and a throwaway reference is made to them destabilizing the Bourbon dynasty, just like the original count did in The Affair of the Diamond Necklace. Finally, Lupin follows the character arc of another French thief, Fantômas, who transformed from sociopath to hero over the course of many adventures–and new audiences.

Two specifically Miyazaki trademarks can be seen in Castle of Cagliostro. He indulged his aviation fascination with the autogyro used in the escape from the castle. Also, Miyazaki often genderbends roles to examine the dynamics of a trope and how gender roles might affect them. Strangely enough, it is Fujiko who takes on this experiment. Her normal skill set lends itself to a Mata Hari seductress spy–her familiar role throughout the franchise. Instead, Miyazaki makes her Lupin’s comrade-in-arms, his Felix Leiter, an old professional and a buddy with experience from countless capers and campaigns. Unfortunately, it also marks a step towards the pixie-fu action girls of today, as the normally glamorous Fujiko is reduced to a man with breasts. Future Miyazaki filns would better show how a woman might function in a male role and retain their femininity. And, as we’ve seen, future Lupin films bring back Fujiko’s sensuality and disdain for modesty.

Miyazaki deftly balances the comedic with the serious and the heroic with the scoundrel, something that the directors and writers which followed him attempted to reproduce. In less skillful hands, this lead to the Flanderization of Lupin and his gang into exaggerated caricatures. That alone demonstrates his storytelling skills, which, with the exception of a fedora-tipping ending, rarely take a misstep. But to truly appreciate Miyazaki’s genius in adapting Lupin III, it is important to know what came before his adaptations. For that, this retrospective will conclude with The Mystery of Mamo and the original manga.

I will note that my issue isn’t so much a lack of acknowledgement of Miyazaki’s contribution to the franchise so much as me noting that there is definitely something forced in the way Miyazaki turns Lupin into an almost entirely heroic character in “Cagliostro”. Even the lighter and softer Lupin needed quite a bit of extra backstory -pretty much never mentioned again – to get to that point.

Besides, it was the fans too, not just me. “Cagliostro” was financially unsucessful when it first came out.

I would hold that “Castle in the Sky” was Miyazaki’s way of remaking “Cagliostro” in a universe of his own design. I always found it the superior film, though I’ve noticed that opinions are surprisingly more split than I thought they’d be.

Lastly – I liked the ending!

I saw Cagliostro last night for the first time in years and even if you don’t compare it with it’s superior predecessor, it still comes up short. There little going on besides a hero rescues princess scenario. The only thing that resembles any kind of substance in the film are the cliches of underhanded politics and Miyazaki’s disdain for vulgarity. When Lupin talks about how horrible he once was, I wanted to puke. Why would you direct a film about a character which you have nothing but contempt for ? It’s baffling.